Since their heyday in classic Hollywood, western genre films have seen a marked decline in their popularity at the box office, along with the corresponding accompanying decline in production. The western genre arguably did more to write the rules of classic Hollywood than any other, serving as a proving ground for countless directors, actors, writers, and crew members.

John Ford, of course, made his most influential and lasting films in the western genre, including Stagecoach (1939), Fort Apache (1948), and The Searchers (1956). A number of other directors worked extensively in the western, including Henry Hathaway, Raoul Walsh, John Sturges, Howard Hawks, and Anthony Mann. Many other classic Hollywood directors briefly flirted with the genre, some making defining classics like High Noon (1952, Dir. Fred Zinnemann).

Beginning in the 1960s and carrying through the early part of the 1970s, filmmakers began to experiment with the standard conventions of the western genre, which had long been about white hats and black hats, showdowns in the middle of town, strong men of action, and women of quiet dignity.

As filmmakers like Sam Peckinpah began to revolutionize the cinematic vision of the west with quiet dramas like Ride the High Country (1962) and sprawling films like Major Dundee (1965), the revisionist western took hold with his 1968 film The Wild Bunch, a violent, expressionistically edited bloodbath that was as much about the deconstruction of the west as it was its anti-heroes.

Many others followed Peckinpah’s example, but brought their own spin to the classic genre and its characteristics: Robert Altman’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1972), and Arthur Penn’s Little Big Man (1970) took the western myth to task in their presentations of cowardly heroes and the problematic portrayal of Native American characters that was endemic to the western genre throughout its history.

The revisionists were not alone – across the Atlantic Ocean, innovators like Sergio Leone were rebuilding the myths of the American west with international casts, sometimes crude filmmaking techniques, and violent stories of revenge and brutality.

The spaghetti westerns, as they came to be known, launched the career of Clint Eastwood, who starred in Leone’s Dollars Trilogy, and with Eastwood a new type of stoic, unpredictable anti-hero who was a far cry from the rugged moral protagonist so often portrayed by John Wayne. These spaghetti westerns, though shot frequently in Spain, reimagined the west in their own way, creating an entire genre distinct unto itself.

And then, the westerns declined. They went, seeming to slide into oblivion, with the odd release notable for its rarity. And yet, the conventions established by the western genre have proven indelible, and have maintained their grip on a number of films that wear their influence, either directly or indirectly. So, the western hasn’t really gone anywhere, except underground.

The clear iconography that suggests an audience is watching a western – the hats and costumes, the sprawling landscape shots, the horses – may be less overt, but they have evolved. The westerns have become something new; they haven’t gone very far at all, in fact.

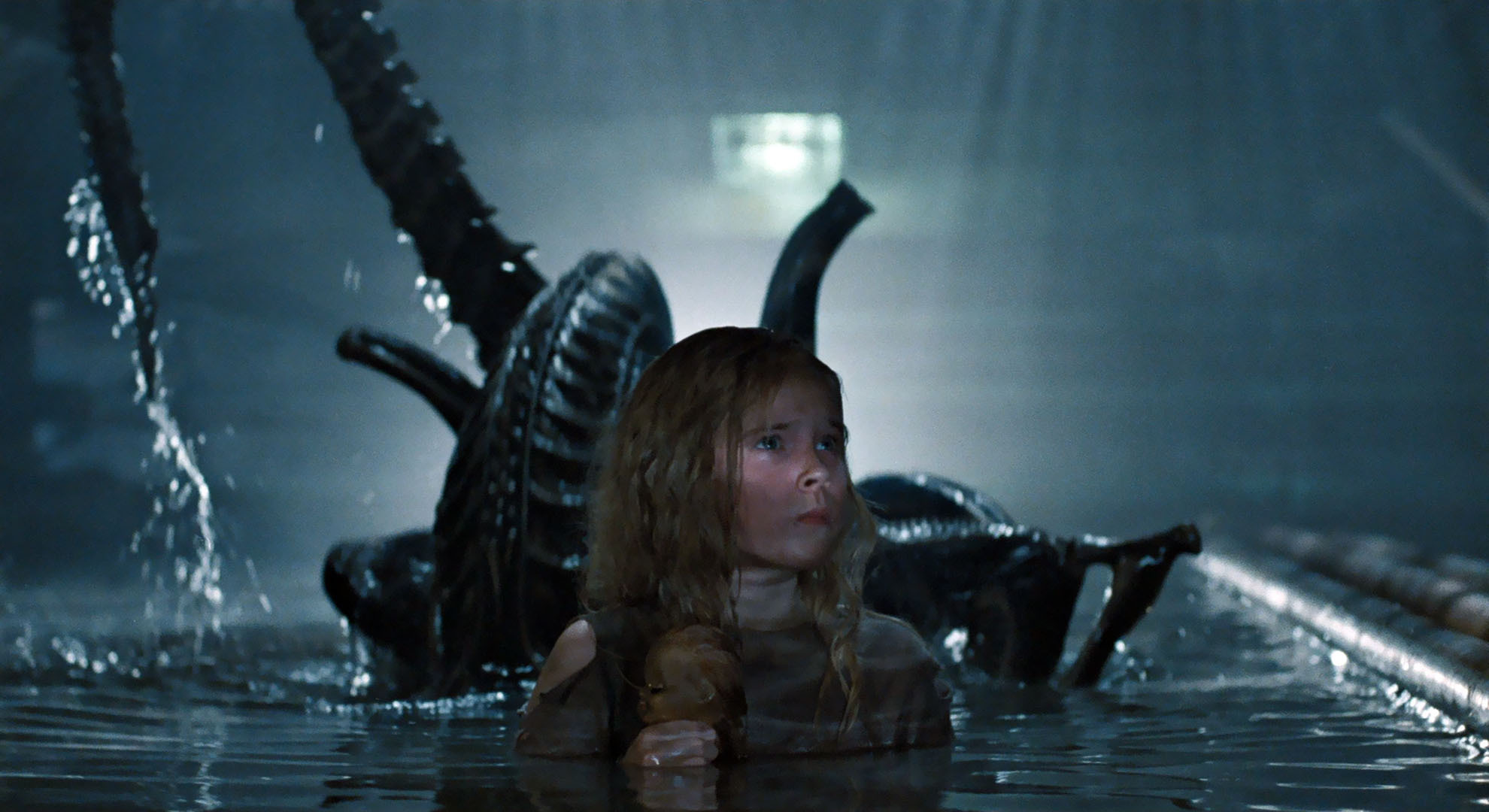

1. Aliens (1986, Dir. James Cameron)

James Cameron’s high-wire sequel to Ridley Scott’s haunted house in space classic, Alien (1979), made everything about the first film bigger and broader.

Instead of a small crew with no weapons, stalked through a cavernous, shadowed spaceship, Cameron’s film sends in colonial marines, led by first-film survivor Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver). There are big weapons, and many more aliens to fend off. The film embraces the frontier nature of space, as the focus of the story is a colony that may have found itself in danger.

In its structure, Aliens is fundamentally about a group of colonists attacked by a native force that it didn’t know was there. The marines, led by Ripley, fill the role of the cavalry, riding out to the distant frontier town to save the townspeople surrounded by hostile forces, be they bandits, Indians, or other dangers. The alien assault on the marines in the nest, a huge action centerpiece of the film, is shot in the style of a classic western ambush, as the humans find they are no match for the aliens on their own turf.

The marines’ last stand, after their numbers have winnowed, is marked by a suspenseful moment in which Michael Biehn’s Corporal Hicks lifts a ceiling frame, only to see a horde of aliens crawling towards the survivors’ position. The crash of James Horner music and explosion of automatic rifle fire resembles countless similar moments in traditional westerns, as the hapless settlers and their cavalry escorts suddenly discover that they aren’t alone.

2. Starship Troopers (1997, Dir. Paul Verhoeven)

Another western goes to space, Verhoeven’s satirical criticism of a militaristic, fascist society, filters the story of the Alamo through the science fiction genre. Like Ford’s cavalry films Fort Apache (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), and Rio Grande (1950), the Mobile Infantry is sent out to distant worlds in an effort to pacify them in the face of a threat, represented in the film by a species of giant space-dwelling insects.

Where Starship Troopers compounds the western story is in both its self-aware approach to the imagery and its treatment of the bugs themselves. First, the planets that serve as the sites of combat are straight out of the American Southwest, with rocky canyons and dusty color, filling the shots with numerous visual cues that recall the most well-known films of the western genre.

Most tellingly, though, under Verhoeven’s sharp satirical direction, the film initially presents the bugs as mindless, animalistic insects animated by nothing more than bloodthirst. In the introduction of the ‘brain bug’ near the film’s conclusion, Verhoeven slyly pokes at the western film’s traditional depiction of its non-white, often faceless antagonists (Mexican bandits, the ubiquitous Native Americans) which represent little other than threat to white settlers.

3. Heat (1995, Dir. Michael Mann)

While on its surface, Mann’s classic cops-and-criminals epic seems much indebted to the generic tropes of film noir – Mann’s images, though in color rather than black and white, are full of rich shadows and harsh contrasts – it actually shares quite a bit of western parentage, as well.

Though Mann’s ambition with the nearly three hour Heat is much greater than a simple genre exercise, the conventions of the western propagate, even if their presence is merely to provide the audience with a framework for the film’s character relationships.

Al Pacino portrays Vincent Hanna, a Los Angeles lawman characterized by dogged obsession and commitment to catching whomever he happens to be chasing at the moment. His mirror and narrative double is Neil McCauley (Robert DeNiro), a professional thief of the highest order whose commitment to his work is just as strong as Hanna’s.

McCauley leads a gang of thieves, each as professional as he is – they’re a classic western gang, each with defined roles, who work more effectively as a unit than they could individually. In a film replete with mirror imagery, Hanna’s posse of fellow cops matches the thieves person for person.

The three most important female characters in the film, Charlene (Ashley Judd), Eady (Amy Brenneman), and Justine (Diane Venora), seem drawn as the same kind of women that populate the western: dignified, but marginalized by the men in their lives. However, the conclusion of the film is perhaps the strongest association to the western genre.

In a pursuit that acts as a more suspenseful, cat-and-mouse version of the high stakes shootout on main street at high noon, Hanna hunts McCauley through the fields of the Los Angeles airport at night. As the western ends, so does Heat; the black hat (McCauley) is laid low by the white hat (Hanna).

However, the outlaw and the lawman perhaps have never understood each other more than they do in Heat’s closing shot, as Hanna grasps the dying McCauley’s hand, ushering the outlaw into death with the comfort of recognition.

4. The Dark Knight (2008, Dir. Christopher Nolan)

If the western was the most popular film genre for much of the classic Hollywood era, it wouldn’t be too much of a leap to say that the primary story of the early part of the 21st century Hollywood cinema has been written by the authors of comic books. While comic book films certainly were made prior to the year 2000, it seems only since then that they have begun to utterly dominate the blockbuster market, not unlike the westerns of a bygone era.

And the comic book films draw on the same kind of mythology that westerns did: larger than life heroes and villains, clear moral lines, and climactic battles for the soul of good. Perhaps none of the more recent comic book films is closer to those westerns than Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight, which appears to remix both the western genre tropes so common to other comic book films, along with the law-and-outlaw structure of Heat.

The Joker’s elaborately designed heists, and especially the opening bank sequence, has all the thrill of a classic western train robbery, with its careful planning and exquisite timing. Nolan’s fluid camera follows The Joker’s plan as it comes together, just as similar elaborate heists do in films like The Wild Bunch and The Badlanders (1958, Dir. Delmer Daves).

Beyond the action sequences, Nolan complicates the lines of good and evil, of course, more so than other comic book films, making this film a prime example of the maturation of the western into something more ambiguous.

5. Big Trouble in Little China (1986, Dir. John Carpenter)

There are few modern directors who are bigger fans of westerns than horror master John Carpenter, whose films frequently contain either visual or thematic references to some his favorite films of the genre or his favorite directors, Howard Hawks chief among them.

Carpenter’s frequent collaborator and star of this film, Kurt Russell, is quite a fan of westerns himself, having starred in more than a few – Tombstone (1993, Dir. George P. Cosmatos), The Hateful Eight (2015, Dir. Quentin Tarantino).

And so, it should be no surprise that Carpenter’s collaborations with Russell consistently rely on western genre conventions. Russell’s hapless hero, Jack Burton, is a bit of sendup of the classic western hero, often played by John Wayne.

Russell adopts a bit of Wayne’s iconic delivery for his portrayal of Burton, with all of its swagger and self-assurance, but there’s a bit of a twist – Burton’s not much of a hero. He certainly doesn’t suffer from a lack of confidence; it’s lack of competence that Burton has to reckon with.

The film’s broad comedy masks some of its western influences a bit, but Carpenter notes in his commentary for the film that the story was originally conceived as a western, with Burton riding into frontier, gold-rush era San Francisco on a horse, instead of his truck, The Pork Chop Express. Chinatown is the same, however, and it is as alien a place to Jack as it would have been had the film been produced as a traditional western.

6. The Devil’s Rejects (2005, Dir. Rob Zombie)

Rob Zombie’s violent sequel to his debut feature, House of 1000 Corpses (2003), owes as much to the western as it does to the tough road films of the 1970s. The grainy images are pure Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974, Dir. Tobe Hooper), of course, but Zombie fills the film with a preponderance of western iconography, steeped in the tradition of the revisionist westerns of the late 1960s and 1970s.

Zombie’s primary exercise in The Devil’s Rejects is largely to drop the house of horrors angle that guided the first film, and to take the characters and the genre he’s lifting in a different direction.

As Otis, Baby, and Captain Spaulding head out on the road, running from the law in hot pursuit, Zombie ditches the horror clown makeup for Spaulding and the rest of the characters, giving them instead a grimy, dirty look that’s more at home in the dusty west of Sam Peckinpah than in the slaughterhouses of Tobe Hooper.

The runaway Fireflys take temporary refuge in Charlie Altamont’s (Ken Foree) Western Fun Town, allowing the characters to spend some time walking on creaking floorboards and through swinging saloon doors, hammering the western influences home.

They reach their peak, though, as the film climaxes – the fugitives run into a roadblock, and decide to drive straight through it, guns blazing, as Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Free Bird” provides the musical accompaniment. The end is pure Wild Bunch and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, with the outlaw characters deciding to go out on their own terms.

7. The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada (2005, Dir. Tommy Lee Jones)

An esoteric film with a complex, non-linear structure, star Tommy Lee Jones’s directorial debut is set in the contemporary southwest and explores the complex relationship between a rancher and an immigrant farmhand, the Melquiades Estrada (Julio Cedillo) of the title.

The story primarily concerns Melquiades’s accidental death at the hands of a border patrol agent, played by Barry Pepper. Jones’s rancher, Pete Perkins, a misanthropic western archetype of the first order, commits to return Estrada’s body to his hometown in Mexico, going so far as to kidnap the border agent to accompany him.

The film has a dreamlike quality to it, as textual intertitles inform the viewer of each of Estrada’s burials, segmenting the film into chapters. While its visual references to the western are quite obvious, with the costumes and use of horses for conveyance, its thematic ones are present as well. In fact, in choosing a border setting for the main action, the film explores the ways in which the west itself has changed for the twenty-first century.

Perkins seems like a man out of his time, who wants to do what he perceives as the right thing by returning his dead friend to his home; he’s forestalled by layers of bureaucracy, as the sheriff initially won’t release the body, then buries it in a cheap box just to put the problem to bed.

His quest south to Mexico also recalls films like The Ride Back (1957, Dir. Allen H. Miner), which, like many other westerns, uses as a framework the device of a man escorting another man to a kind of justice. The irony of the new west in 2005, of course, is that it’s Pete who likely faces trouble, for kidnapping the border agent. In this film, an old world has gone, and Perkins doesn’t understand how to live in the new one.