A point-of-view (POV) shot is one where the camera is positioned in such a way to give the audience the impression that they are viewing the scene as a character in the film. It creates the effect that the viewer is immersed in the action, as if he/she were directly taking part in the movie itself, as opposed to a deep-focus or master shot where the viewer is placed outside of events, passively observing like a “fly on the wall”.

There are various types of POV available to the film-maker: the ‘subjective viewpoint’, for example, can be used to replicate the first-person narrative of a novel by showing the action through the eyes of the central character, whereas a more objective experience may be achieved by placing the camera cheek-to-cheek with another actor in the film to show what that character is able to see without implying that the viewer is actually taking part in their place.

These kinds of shots are often followed immediately by a close-up of the character in order to show his/her reaction to what they (and the audience) have just seen — an editing combination known as “shot, reverse-shot”. A similar type of POV angle, regularly used in action movies, is where the camera is placed close to ground level alongside one of the wheels of a speeding car, adding excitement through a feeling of participation in the drama of a chase scene.

POV shots have been used by directors since the dawn of cinema and they are a standard part of the film-maker’s toolkit. One of the earliest well-known uses of the technique is in Napoleon (Abel Gance,1927) when the camera was wrapped in protective padding and then violently punched around the set by a group of actors in order to recreate the ordeal of the central character being beaten up.

Orson Welles originally planned in 1939 to film an entire version of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (later transplanted to the Vietnam war and shot from regular angles by Francis Ford Coppola in Apocalypse Now) entirely as a first-person narrative from the protagonist’s perspective. He discarded the idea as impractical, however, and concentrated on Citizen Kane instead; although he did later revisit the technique in 1952 when he used POV in his 1952 adaptation of William Shakespeare’s play, Othello.

Some directors, such as Alfred Hitchcock, are famous for using point-of-view cinematography in many of their works to build suspense or add to the sense of fear they are trying to instil in the audience. The technique is especially beloved of horror and thriller filmmakers who can use it to show the villain’s actions without revealing the identity of the culprit.

Nowadays, POV photography is everywhere and has become totally ubiquitous as just about anybody can go out and buy a Go-Pro camera, strap it to their ski- or bike-helmet and start filming away; Facebook and YouTube are full of first-person accounts of thrill-seekers hurtling down black runs or bumping along single-track mountain trails. It is the more memorable cinematic examples, however, that shall be examined in the following list.

10. Lord of War (Andrew Niccol, 2005)

Loosely based on the Russian arms-trafficker Victor Bout (played by Nicolas Cage), who allegedly sold or transported weapons to opposing sides in the same conflicts, and starring Ethan Hawke as the UN inspector pursuing him, this movie was endorsed by the humanitarian NGO Amnesty International for showing the duplicity of world governments in their contradictory approach to the international armaments industry.

Remarking upon the economic scale of the global operation which his film sought to represent, director Andrew Niccol revealed at a press conference that, for a scene featuring a stockpile of over 3000 Kalashnikov AK-47 assault-rifles, it was cheaper and easier to go out and actually buy the real weapons than it was to make or procure fake props. Presented almost as a ‘film within a film’, its opening-credits sequence starkly portrays the birth, life and death of a bullet in first-person narrative.

The nearly three-minute-long continuous shot, from the POV of a camera mounted on the back of a bullet casing, traces its transformation from a piece of flat metal and subsequent journey around a munitions factory, through its transportation around the world facilitated by corrupt government officials, to various foreign armed-forces, then loaded into the magazine and up into the barrel of a sniper’s rifle and finally, with cold and clinical brutality, into the head of an African child-soldier.

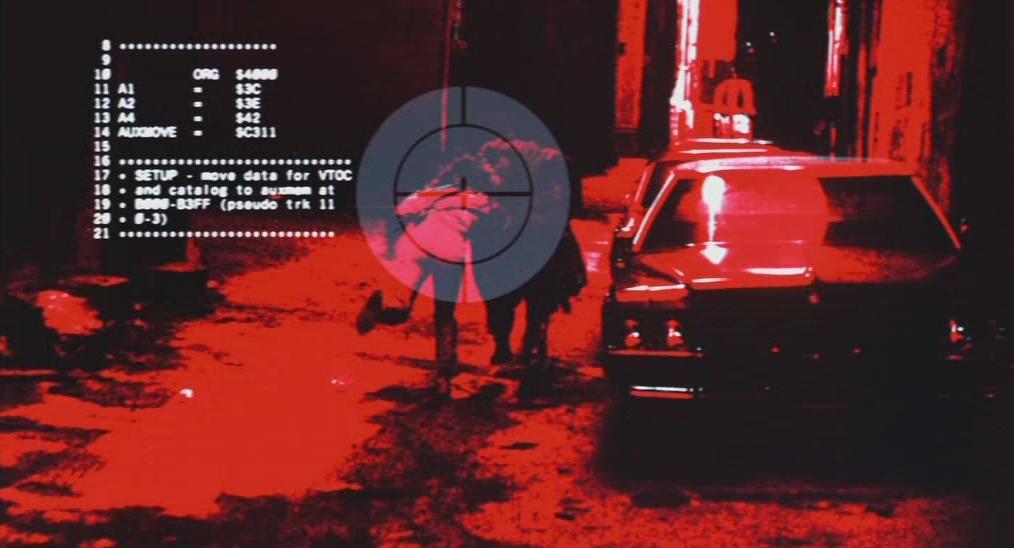

9. Strange Days (Kathryn Bigelow, 1995)

Written by James Cameron who also penned The Terminator and Titanic, this dark and brooding sci-fi is set in Los Angeles at the end of the last millennium. It is built around the intriguing premise that a person’s memories, including their emotional and physical experiences, can be recorded from their cerebral cortex directly onto a disc and then replayed through a squid-shaped headset straight into the nervous system of another person who can feel everything that the person who recorded the disc went through.

The portrayal of scenes in which characters wear the headsets and play back those memories is shown onscreen from the perspective of the person who experienced and recorded them. It makes for some below-the-waistline entertainment when the subject of the disc is a nubile adolescent girl intimately washing herself in the shower, or a ‘John’ enjoying the services of two prostitutes as they writhe and cavort in bed with him.

They take a more sinister turn, however, when the subject is a psychotic killer recording everything he sees and feels as he commits a violent murder. They become darker still when the recording is made from the POV of the murder victim herself as she is viciously raped whilst simultaneously being choked to death.

8. Halloween (John Carpenter, 1978)

Committed to an institution as a six-year-old child for murdering his sister, Michael Myers escapes fifteen years later and returns to his home town to terrorise successive generations of teenagers on Halloween night. In doing so, the homicidal maniac in the white mask, who is referred to simply as “the shape” in the original film’s end-credits, spawned a long-running franchise comprising ten movies, a video game, multiple novels, comic books and a range of not-so-cute merchandise.

The adult Myers, played by Tony Moran, speaks no lines at all in the film and is shown mainly from first-person point-of-view. As well as ratcheting up the tension and concealing his identity, the use of a shaky, hand-held camera combined with POV shooting helps to impart Michael’s disturbed and deranged state of mind to the audience as we accompany him on his killing spree.

7. The Terminator (James Cameron, 1984)

The first feature in the time-hopping cyborg franchise had Arnold Schwarzenegger playing the role of the bad guy. Long on hight-tech special effects but short on deep-meaning philosophical soliloquies, the killing machine of the title is sent from 2029 back to the present day (1984) to eradicate the mother-to-be of a rebel leader in a future war against a robot army.

Many of Arnie’s scenes are filmed from the optical POV of his “T-800” cyborg’s vision and resemble the head-up display of Google Glass or a VR gaming headset in the way that digital information about targets, weapons, attack strategies and the like is presented to the assassin. This perspective reminds the viewer of the mechanical nature of the central character and reinforces his lack of humanity and inability to feel empathy with his victims.

Whilst not known strictly as a ‘method actor’, an anecdote exists about Schwarzenegger wandering into a downtown LA restaurant still in full Terminator make-up during a break in filming; apparently, he picked up a few strange glances from other diners as he ordered lunch whilst sporting an exposed jawbone, empty eye-socket and burnt-away cheek-flesh.

6. Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958)

‘Sight & Sound’ (the venerable magazine of the British Film Institute) polls a selection of internationally respected film critics and industry experts once every ten years to formulate a list of what they consider to be the ten greatest movies of all time.

For fifty years, Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941) dominated the top of that chart; but in 2012 the cognoscenti voted that Hitchcock’s suspense movie about the influence of the dead over the living, set in San Francisco and starring James Stewart and Kim Novak, had usurped Citizen Kane to reign supreme as the greatest film ever made.

There are many reasons why this classic film is so eminently watchable; one of them is the masterful way that Hitchcock uses point-of-view cinematography to represent the symptoms of suffering a fear of heights.

The English auteur is renowned for using camera angles to endow his films with a sense of fear or anxiety but, in Vertigo, he takes the technique a stage further to replicate, almost viscerally, the effects of acrophobia. Incidentally, this movie also pioneered the use of the “dolly-zoom” manoeuvre, where the camera is tracked forwards towards the subject whilst the zoom lens is pulled in the opposition direction (or vice versa); some film-makers still refer to this technique as the “Vertigo effect”.