Carl Jung’s ideas have had a profound influence on modern culture. As the founder of analytical psychology, his theories and thoughts have inspired countless texts, novels, and varied media ranging from comic books to video games.

Perhaps no psychiatrist (even Freud) has had as much of an impact of the development of narrative in the modern era.

In film however, Jung’s work is often interpreted in less overt ways, but are yet still steeped in the mythos that permeated his work.

The following films are ones that are inextricably influenced by Jung or could be read with conscious or unconscious Jungian motifs in mind.

10. Prometheus (2012)

Ridley Scott’s Prometheus is inherently tied not just to the Myth of Prometheus (the Greek deity who is said to have created humanity and provided fire, and thus knowledge to them) but also to the facets of Jung’s ‘Mythic Unconscious’, the collective myths touched upon earlier in the discussion of Smith’s Heaven and Earth Magic.

In the film, we see a group of astronauts/explorers searching the ruins of an ancient civilization in order to investigate the origins of humanity. In a sense, this is a sort of reversal of the Promethean myth, with the humans seeking out their ancestors rather than having been subservient to them.

These explorers, believing that the ‘Engineers’ (the analogue for Prometheus in the film) hold the answers to our origins are in essence projecting their ideals upon the extraterrestrials, enforcing their internalized collective myths that have been invoked and re-invoked for centuries.

The film focuses on our assumption of power over our environment (and our evolution, not just biologically but psychologically), when in reality much of our perception of these things is just a superimposition of our ideals over the external.

The AI, David (Michael Fassbender) is Scott’s way of attempting to delineate the division between our consciousness and our ego. David, in the process of the film begins developing emotions, which suggests that he is developing consciousness. However, as he begins to develop these feelings, Scott suggests that without properly being exposed to the cultural collective, David’s agency can be subsumed by his own myths (such as his veneration for Weyland/The Engineers).

Prometheus can be seen as a parabola, intertwining the notions of collective myths and the development of self as a subset of mythological and collective storytelling.

9. A Star is Born (1937)

William A. Wellman’s A Star Is Born is something of an odd choice, but nonetheless forces its audience to encounter Jung’s idea of archetypology and particularly his concept of self-realization vs. the shadow.

A Star is Born concerns the life of Esther (Janet Gaynor), a midwest farm girl who dreams of becoming a movie star.

We see throughout the film that despite constantly being reminded of her roots, she attempts to reinvent herself in the Hollywood mould, taking up the name ‘Vicki Lester’.

In this way, Esther kills her midwestern persona and adopts that of ‘Vicki’, a successful movie star. Though less harrowing or direct than Bergman’s films, we see here Wellman’s attempt to deconstruct the illusory mask of fiction and shine light upon Jung’s concept of the shadow.

With the ‘death’ of Esther and the adoption of the ‘Vicki’ persona, Esther attempts to realize a sense of self that combats her ‘true self’ with the result being various manifestations of neurosis and depression.

Near the end of the film, Esther attempts to synthesize both her former life as Esther and her current ‘Vicki’ persona proclaiming that ‘This is Mrs. Norman Maine’, another identity that is neither Esther nor Vicki.

8. Abre Los Ojos/Vanilla Sky (1997/2001)

Alejandro Amenábar’s Abre Los Ojos and Cameron Crowe’s English language remake are nearly identical and as such I’ve included them in one entry, though there are those who might have their favorite iteration.

Both films are decidedly unconcealing of their use and inspiration of Jungian psychology. The protagonist in both films uses a somewhat frightening mask that is devoid of defining features in order to interact with society following a disfiguring car accident.

In this way, both Amenabar and Crowe make use of the persona as narratological tool to dissociate the audience from the intentions or perhaps the reality of the narrative.

Of high note is the use of archetypes in both films. Jung wrote that people maintain a sort of idealized perception of a lover and project that ideal onto the ‘person of the beloved’, which is seen in the form of Penelop Cruz’s character of Sofia/Sophia (oddly enough, Cruz appeared in both the original Spanish production and the American remake).

In a sense, we could see the unreality of the films (best seen in the prolonged dream sequence of the film) as a sort of malfunction of idealized projection in a subject that has experienced a traumatic break in their persona. This depiction of neurosis and suspicion of reality speaks to the ‘shift’ of perception which Jung speaks of being a central tenet in the spiritual and psychological development of a psychic unity of the subject.

7. Heaven and Earth Magic (1962)

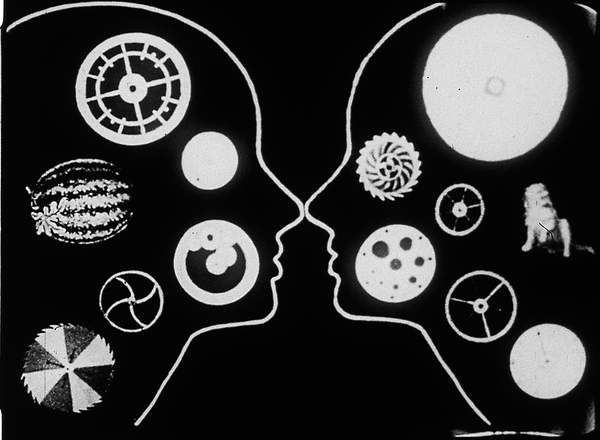

Harry Smith’s Heaven and Earth Magic is an iconoclastic entry in the art of animation. Its use of cut-out figures sourced from newspapers and magazines seem to be a thematic statement that is similar to Jung’s notion of cross-cultural archetypes that are present in societal consciousness.

It depicts the apotheosis of a figure (simply named the heroine) as she ventures from Earth through to heaven and back again.

In this sense, the apotheosis of the figured created from the remnants of mass media could be seen as a commentary on the proliferation of common mythologies throughout the world.

Common mythology and its subsequent inclusion in a collective unconscious is central to Jung’s idea of self, in that our most basic ideals are formed by our external collectives and then subsequently extrapolated upon internally as we develop into personhood.

6. The Holy Mountain (1973)

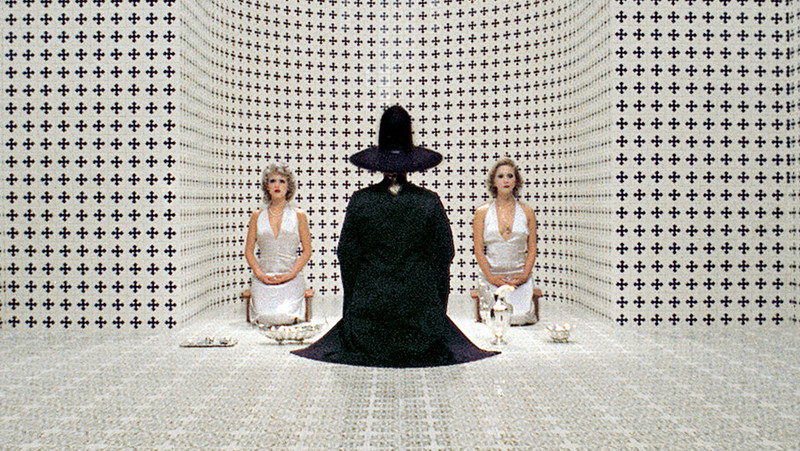

Alejandro Jodorowsky’s the Holy Mountain is infamous as a psychedelic cult film, and is incredibly indebted to Jung’s work on symbology and iconography.

Jodorowsky is an admitted obsessive when it comes to iconography and seems to have been partially inspired by Jung’s work ‘Man and His Symbols’.

Speaking to the mythopoetics that we have already encountered, Jodorowsky uses Jung’s concept of collective mythology in order to envisage a sort of alternate-reality that’s more open about its use of collectively created and understood symbols, such as anthropomorphized depictions of planets/gods, as well as archetypal figures exemplified by Jodorowsky as an alchemist (Jung’s wise old man).

It also touches upon the projection of narratological unreality upon fictional narrative and ends with a profundity that is perhaps a reflection of Bergman’s work in Persona.

It is undeniably a trip through and without ego, perhaps a film without an equal in terms of its understanding of mythopoetics and its effects on the phenomenology of consciousness.