“In my film, time is shattered.”

– Alain Resnais

In search of lost time

Wow. How enticing it is to consider and suppose that the cinema of the subconsciousness and of memory barely held breath before 1959, when French film director Alain Resnais intimately accepted the subject matter with fascinating affection in his first step feature, the monumental Hiroshima Mon Amour.

As a restoration of romance and surrealism on screen Resnais’ debut stands nonpareil with the ability to shock and impair audiences with its innovations, its repentance, and its tenderness. If ever there was a film of the New Wave that maintained an open-door representation of cinema as art, that film was Hiroshima Mon Amour, without a doubt.

Resnais, who never quite fit the fingerprint of auteur – the writers he collaborated with always bore their distinctive predications rather resolutely – had a brightly shining original screenplay, Oscar-nominated I might add, by the effulgent French writer Marguerite Duras. The feminine substructure therefore, buttressed by Emmanuelle Riva’s star-making lead performance, was the triple threat of illustrious, intellectual, and authentic.

Duras’ screenplay is a discerning work of invention, and an intensely literate one. Her non-linear narrative and non-stop use of flashbacks garnered the film Proustian comparisons straight away.

The overlapping narratives and the amalgam of past and present echo A La Recherche Du Temps Perdu but also noted works by the likes of James Joyce and Virginia Woolf brand their bright little “x” in places also. Here came a film that had almost no cinematic antecedents, only literary ones, making for a novel idea, literally and figuratively.

“After Hiroshima, Mon Amour, everything must change, for the cinema and the individual. This is a film that remakes the conscience of the individual.”

– Le Monde

To burn with desire and keep quiet about it

It’s funny, to me, to recall the first time I saw Hiroshima. It was in 1997, the inaugural viewing in a film aesthetics class I was taking and I remember watching it in a small auditorium filled with my fellow film students, many of whom were in a hurry for class and the screening to be over so they could catch Simon West’s silly waste of celluloid, Con Air, which had just opened.

I tagged along for that, too, but truly my mind had been recapitulated by Resnais’ deeply affecting rumination on emotional memory, and no mullet-sporting Nicolas Cage rejoinder was going to bring me down from the lofty heights Hiroshima had laid out for me.

Resnais’ film begins, sort of, in the summer of 1957, in Hiroshima. Here we meet a French actress from Paris, we never learn her name, but Emmanuelle Riva’s performance is one for the ages. Riva, till then, had been a theatre actress of some acclaim, her turn in Hiroshima Mon Amour however, would garner her much deserved attention, to the point that she’d attain a type of iconography as well as being viewed as one of the Nouvelle Vague’s pacesetters.

Essentially retired, Riva, now 88, recently returned to the screen in 2012 in Michael Haneke’s acclaimed Amour (which incidentally won Riva a BAFTA, a César, and an Oscar nomination, as well as being the perfect bookend; her film career launched with Hiroshima Mon Amour and consummately brings down the curtain with Amour).

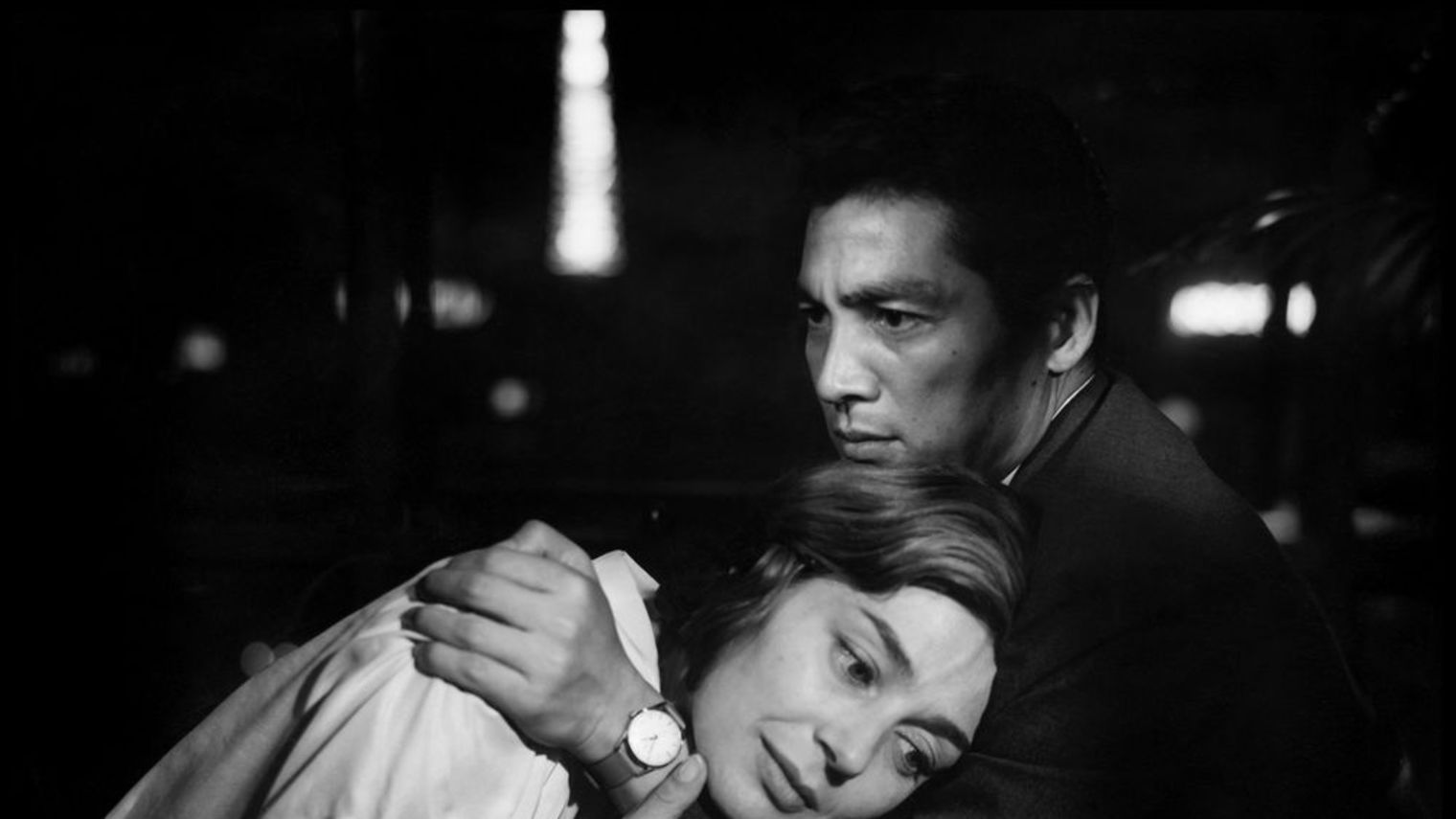

In the city of Hiroshima, Riva’s actress is making a film and it is here that she meets a Japanese man, an architect, also nameless, played with sentiment and ascendancy by Eiji Okada. The two come together and drift through Japan in an elliptical, time-twisting miasma of memory and yearning, with a burning in their marrow, flames at their core.

Their affair is tiny and delicate, like a pink baby bird, too small to soar. Ad interim the desolation and post-apocalyptic shadow of 1945’s nuclear bombing and the spectre of a lover lost in German occupied France, making for them a death shroud.

“I think that in a few years, in ten, twenty, or thirty years, we will know whether Hiroshima Mon Amour was the most important film since the war, the first modern film of sound cinema.”

– Éric Rohmer, director (My Night at Maud’s, Claire’s Knee)

“The most beautiful film I’ve ever seen.”

– Claude Chabrol, director (Le Beau Serge, La Cérémonie)

How could you rise anew if you have not first become ashes?

The doomed cross-cultural romance of the leads – both have families far away, spouses, kids – made fireworks for late 1950’s audiences. That the film took such a strong anti-nuclear stance and juxtaposed images of intimacy with bodies of burn victims, did much to court controversy.

Close-ups, gorgeously framed by cinematographers Sacha Vierny and Takahashi Michio, each at the peak of their appreciable powers, combine with sensual images of the couple making love, bodies intertwined, rocking, holding, caressing, crash cut with maimed hands, mutilated bodies, and the atomic destruction blankety-blanked upon the denizens of Hiroshima make for a monstrous melange of adulation to destruction, desire to dread, caresses to curses.

It’s a compelling feat, absorbing and aberrant in one fell swoop, the skill of editors Henri Colpi, Jasmine Chasney, and Anne Sarraute is the stuff of legend. Nicolas Roeg certainly took heed of this device in his approach to scene construction (his intimate and elegant love scene from Don’t Look Now springs to mind) and more recently an homage was paid to this tactic on the ABC television series How to Get Away With Murder.

By creating an intimate space for the viewer, in this case the lovers, by establishing a clandestine and cherished breadth, and then violating that space with full-on horror makes for a utilizable facsimile of what really went down when Little Boy was dropped, reducing a populated city to ash and the people there along with it. Tying a collective misfortune on such a monumental scale with a tiny, individual experience is part of Resnais’ tinselling brilliance and glittering generosity.

“[Hiroshima, Mon Amour] is a circular film. At the end of the last reel you can easily move back to the first, and so on. Hiroshima is a parenthesis in time. It is a film about reflection, the passage of time is effaced because it is a parenthesis within duration. And it is within this duration that Hiroshima is inserted. In this sense Resnais is close to a writer like Borges, who has always tried to write stories in such a way that on reaching the last line the reader has to turn back and re-read the story right from the first line to understand what it is about – and so it goes on, relentlessly. With Resnais it is the same notion of the infinitesimal achieved by material means, mirrors face to face, series of labyrinths. It is an idea of the infinite but contained within a very short interval, since ultimately the ‘time’ of Hiroshima can just as well last twenty-four hours as one second.”

– Jacques Rivette, director (Celine and Julie Go Boating, La Belle Noiseuse)

Resnais, who passed away in 2014 (March 1, 2014) at the age of 91, was a prolific innovator and true master, busy making films till the very end.

Hiroshima, Mon Amour was a landmark modernistic masterwork to be sure, and he replicated artistic success numerous times throughout his long and celebrated career – a career that spanned some six decades, punctuated by such audacious and exemplary works as Last Year at Marienbad, Mon Oncle d’Amérique, and Wild Grass – Resnais was a malcontent the likes of which cinema may never see again.

Hiroshima Mon Amour’s anti-war stance resonates with such bitter beauty, to think, it was withheld from competition at the 1959 Cannes Film Festival so to assuage American sentiment – it’s agonizing, absolutely heart-rending anti-nuclear posturing was deemed anti-American by pundits at the time – where it still received the International Critic’s prize.

A world wide art house sensation, few films pack the emotional lambaste presented herein. To love cinema, it is fair to say, is to love Resnais’ magnanimous entrée, an authentic dissertation on tenderness, cruelty, and forgetting.

As Riva’s actress, having offered a brave valediction to Okada’s architect in a bustling late night cafe, departs, walking away from one another, neither turning to steal a parting glance. She morosely contends in an inner monologue:

“Who are you?

You destroy me.

I was hungry. Hungry for infidelity, for adultery, for lies, hungry to die.

I always have been.

I always expected that one day you would descend on me.

I waited for you calmly with infinite patience.

Take me. Deform me to your likeness so that no one, after you, can understand the reason for so much desire.

We’re going to remain alone, my love.

The night will never end…”

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.