The term “aspect ratio” describes the mathematical relation between the horizontal side of the screen image and the vertical one; for example, the ratio used for television is 16:9, which means that the proportion between width and height will always be 1.78 to 1 (if your tv screen is 16 inches long, its height will be of 9 inches).

In cinema, this proportion was initially determined by the physical structure of film stock, which had four perforations in height; the image resulted as a rectangular frame with the ratio of 4:3, or 1.33:1. For many years this was the standard, and it was only slightly modified in 1932 when the addition of the sound stripe to the film roll brought the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to standardize the so-called “Academy ratio” of 1.37:1.

With time, many filmmakers and distributors started to experiment with different kinds of film and ratios, especially after the birth of television, which initially adopted the same 1.37 proportion of movies. The direction of these experimentations was towards widescreen projection, and after decades of attempts, the industry settled on the widescreen formats of 1.85 and 2.35 which are still the main choice for filmmakers today.

The choice of the aspect ratio is a primary step in giving a film its identity, and even today many directors choose different variations of ratios for artistic purposes, often watching back at that period were the industry was moving on from the Academy ratio and trying different versions of widescreen.

For example, in 2015 Quentin Tarantino, as much a cinephile as a director, revived the Ultra Panavision 70, a system which shoots in 70mm film and produces a very wide image (2.76:1); the Ultra Panavision 70 hadn’t been used since 1966.

Here are ten other movies which adopted unusual and experimental aspect ratios in a particularly notable way, ranked in chronological order.

1. Napoleon (1927)

This 1927 silent film by French director Abel Gance was supposed to be the first in a series of six movies about the life of Napoleon, but the project never came through; nevertheless, Napoleon is still hailed as one of the cornerstones in the history of silent film.

There have been numerous attempts of restorations of the film; these editions vary from 129 to 562 minutes and have been supervised by the likes of Francis Ford Coppola, Henri Langlois, legendary film preservationist Kevin Brownlow and Gance himself.

In the era of still shots, Gance experimented with moving camera takes and frequent cuts; he also employed other revolutionary techniques like p.o.v. shots, split screens and multiple-camera setups. While most of the film was shot in the usual 4:3 ratio, Gance decided to make the finale as impressive as possible and employed a widescreen format.

At the time, 70mm film wasn’t already in use, so the only way to create a widescreen effect was to shoot the scene with three normal cameras put next to each other, and then project them simultaneously. The resulting image had a proportion of 4:1; this technique was given the name of “Polyvision” and was developed exclusively for Napoleon and its so-called “triptych” final sequence.

As impressive as it was, the shooting and projection of Polyvision sequences proved extremely difficult, and the format was quickly abandoned.

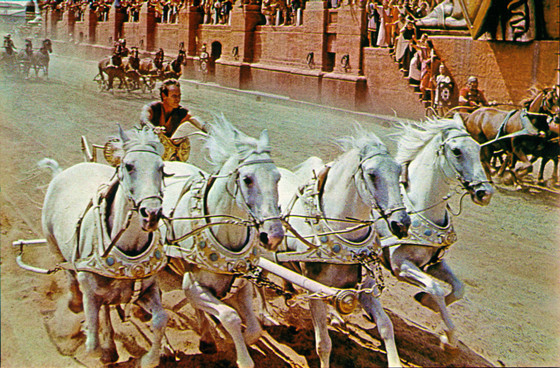

2. Ben-Hur (1959)

Ben-Hur, released in 1959, was shot in Rome’s legendary studios of Cinecittà and was one of the most impressive productions movie history had seen up to that point. During the nine-months shooting the budget went up to $15 million, the biggest the industry had seen yet; 9 sound stages and over 300 sets were utilized, as well as 10,000 extras, 100.000 costumes and hundreds of animals. The legendary chariot race sequence alone took 5 weeks spread over 3 months and more than $1 million to shoot.

Director William Wyler worked with director of photography Robert L. Surtees, who in agreement with MGM executives decided to shoot the film in widescreen format, a choice Wyler initially fought, since he found too many elements were in the same shot, and the viewer’s attention could be easily lost. The ratio of the movie is a very wide 2.76:1 which was created by employing 70mm anamorphic camera lenses and 65mm film stock.

The peculiar and impressive aspect ratio of Ben-Hur was one of the main factors in making it the quintessential “epic movie” and helped shape this epic genre’s look.

3. Spartacus (1960)

A year after Ben-Hur, another legendary historical movie was released, Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus. The film was written by then black-listed Dalton Trumbo and starred Kirk Douglas, who was rumored to be promoting the making of the movie after having been passed on for the role of Ben-Hur himself.

The original director chosen by Universal Studios was Anthony Mann, who was fired after just one week; his replacement was then 30-year-old Stanley Kubrick at his first big production (this occasion marks the last time Kubrick shot a film without complete artistic control).

The format of the film is 2.20:1, similar to the widescreen ratio of 2.35 many films have used in the last decades after the invention of Cinemascope; in this film the 2.20:1 ratio is obtained through the use of 35mm film in a then-experimental screen process called “Super 70 Technirama” which ran the film horizontally.

Spartacus is a perfect example of Hollywood’s persistent attempts for wider screens and better definition between the 50’s and 60’s, a period when the field was open for enterprises ready to fill the new needs of cinema viewers.

4. How the West Was Won (1962)

“Cinerama” is the name of a projection system created in the very early 1950’s which used three 35mm cameras with 27mm lenses shooting 35mm film at a six perforations height. This unusual technical setup resulted in the projection of a deeply curved screen which had the aspect ratio of 2.59:1.

This employment of three projectors at the same time was a very complicated process, even more than the “triptych” one Abel Gance developed for his Napoleon, but the spectacular effect of the widescreen image made it immensely popular. Cinerama was mainly used for exhibition screenings, often in roadshows.

The only dramatic films made with Cinerama ended up being The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm and How the West Was Won, both released in 1962.

How the West Was Won is an epic movie which had John Ford, Henry Hathaway and George Marshall as its directors, and was produced my MGM. The story is spread through most of the 19th century and follows the travels of four generations of the Prescott family.

How the West Was Won’s visual impact took advantage from the incredibile width and definition that Cinerama offered, but this process was soon left behind, since shooting an entire movie in Cinerama was too complicated and costly.

5. It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963)

The now standard ratio of 2.35 came with the invention in 1953 of Cinemascope within 20th Century Fox studios. Cinemascope ended up surpassing Cinerama as the main widescreen technique, yet in the early 1960’s Cinerama’s influence was still strong.

One example is It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963), directed by Stanley Kramer. The movie was promoted as the first Cinerama film which only used one projector. What that actually meant was that director of photography Ernest Laszlo shot the film in 70mm film with anamorphic lenses; so, It’s a Mad Mad World was technically called a movie shot in “Super-Cinerama”, or “Ultra Panavision”, and released in Cinerama. Its final aspect ratio was of 2.76:1.

The technical importance of this ambitious and now legendary ensemble-comedy lies in the fact that it employs two fundamental aspects of widescreen projection: the one-camera shooting and the use of anamorphic lenses, which compress the sides of the image on the film frame in order to have it later enlarged, resulting in a wider image.

After Cinerama and Ultra Panavision’s experimentations, Cinemascope was ready to adopt anamorphic lenses and become cinema’s new standard, together with VistaVision’s 1.85:1 aspect ratio developed in 1954 at Paramount Pictures.