It’s hard to overstate the cataclysmic impact of the 2008 global financial crisis on the economy of the United States and the rest of the world.

The stock markets of countries around the globe cratered into oblivion, homeowners found themselves out on the streets, long-time employees packed their boxes and hit the unemployment lines. The shock waves resonated for years after, permanently altering the lives of many people already in the economic system, and those looking to enter it after they graduated college.

With such a profound effect on human life on earth, it was inevitable that film would attempt to engage with the crisis, as it has alternately sought to explain, dramatize, and criticize the behavior of the individuals who contributed to the inflation and collapse of the housing market between 2004 and 2008.

Alternately, however, films focusing on the financial crisis have also sought to humanize, sympathize, and lament the plight of the victims of the crash – those who might have lost homes, jobs, or personal savings through no fault of their own.

To truly understand the complex events that led to the crisis of 2008, however, requires more than to merely see films that are focused directly on those events. What the crash seemed to expose more than any other thing was a systemic failure on multiple levels; it was a collapse accelerated by the increased use of specific financial products, deliberately too confusing for the public to understand (CDOs, CDS, and on and on).

But, the roots of the destruction wrought by the financial crisis go back much further, and have been chronicled on film going back to the 1980s. The legacy of the financial crisis is long lasting, but its origins go back just as long. For a cinematic perspective on the crash, one has to go back just as far.

Please note that the movies on this list are ranked in chronological order.

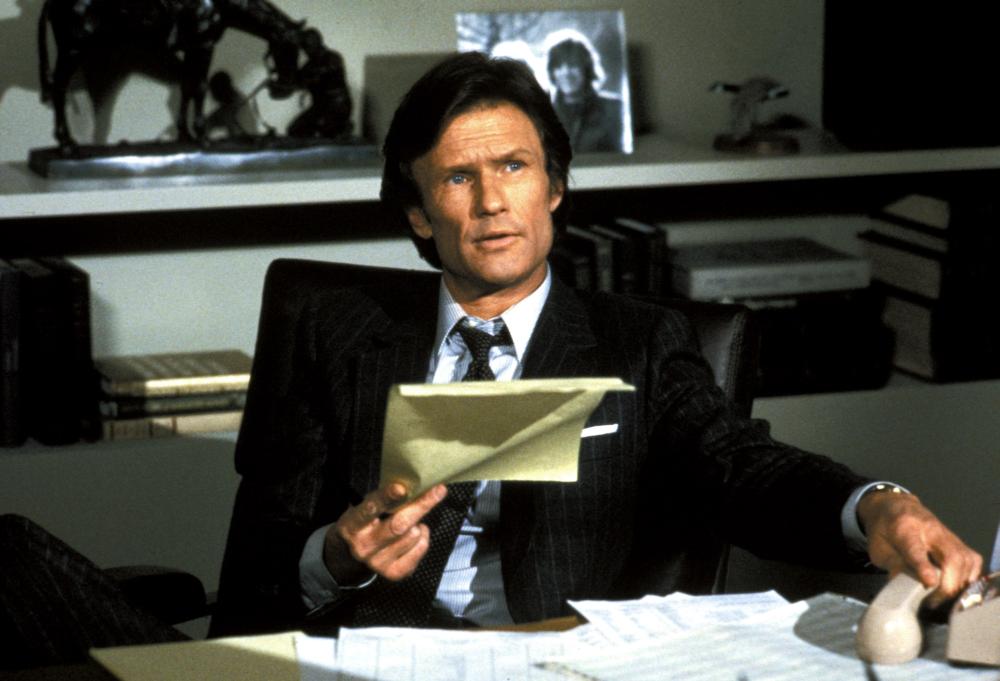

1. Rollover (1981, Dir. Alan J. Pakula)

One of the first films to take place in the world of high finance and investment banking, Alan J. Pakula’s film opens with a series of tracking shots, moving the camera left-to-right across a series of ticking stock quotes, then dissolving to a busy trading floor. Pakula’s opening camera moves attempt to establish a fluid visual palette, putting the world of the canyons of Wall Street on film for an audience that speaks to the increasing relevance of the financial sector in American culture at the dawn of the 1980s.

While other filmmakers may have depicted the world of Wall Street in more compelling fashion, and with more mania, Pakula’s approach is to cloak the proceedings in a dark, heavy fog of conspiracy. The business meetings in his film are conducted in hushed tones, as a group of titans of industry attempt to pull off a devastating swindle, sucking all the capital out of the western markets, causing a total global economic collapse.

Hume Cronyn’s Emery, a captain of industry himself, addressing a group of young students, Wall Street aspirants all, encapsulates the hubris of countless Wall Street characters to come when he tells them: “Banks are more dependable than governments. We don’t lie to ourselves.”

As the film concludes, and the world’s economic system lies in ruins, leading to global upheaval, riots staged by the newly unemployed, and the hollowing out of the trading floor where the film began, Kris Kristofferson’s Hub Smith and Jane Fonda’s Lee Winters sit in the dark, surrounded by the gloomy shadows so characteristic of Pakula’s work.

His 1970s institutional critiques, Klute, The Parallax View, and All The President’s Men, are of a piece with Rollover, taking the same cynical, chiaroscuro perspective on a dark world beneath a bright surface.

2. Wall Street (1987, Dir. Oliver Stone)

Few films immortalized the Wall Street aesthetic more fully than Stone’s late 80s satire of money, lust, and betrayal in the financial sector. Of course, it’s Michael Douglas’s Gordon Gekko, the film’s antagonist, that has held on the longest, elbowing his way into the cultural zeitgeist with his infamous ‘Greed is good’ speech functioning as the centerpiece of the film.

Gekko’s speech was apparently based on a real quotation by Ivan Boesky, an American investor who was convicted (like Gekko in the film) of insider trading.

Stone’s acerbic take on Wall Street greed is personified by his Faustian protagonist, Bud Fox (Charlie Sheen), whose moral descent into Gekko’s world is primarily charted by Fox’s willingness to do whatever it takes to succeed, realizing the consequences only too late.

The central conflict concerns an airline, Bluestar, which Fox’s father (played by Sheen’s real father, Martin) works for. Gekko, seeing an opportunity to take the company public, decides to double cross Fox and sell off the airline because he can make more money.

In its exploration of the tycoons (personified by Gekko and another billionaire played by Terence Stamp) and the working class people who suffer from their whims, the film exemplifies an attitude that created the circumstances of the financial crisis of 2008, playing out nearly thirty years before in microcosm.

The key exchange that illustrates Stone’s perspective on this world takes place in Gekko’s office, when Fox confronts his erstwhile mentor after discovering the latter’s Bluestar Airlines gambit. Fox asks, “Why do you have to wreck this company?” Gekko responds, in a perfect encapsulation of his character’s worldview, with “Because it’s wreckable.”

3. Inside Job (2010, Dir. Charles Ferguson)

With sober narration by Matt Damon, this documentary film was the first mainstream American film to engage directly with the financial crisis. Ferguson’s effort won an Oscar for Best Documentary Feature, and is characterized most strongly by its thoroughly researched, detail-rich examination of the causes of the financial crisis, just two years after it happened.

The organization of the film attempts to help the viewer make sense of the labyrinth of players and financial products that caused the economic collapse, with visually rich descriptions of collateralized debt obligations and credit default swaps. In addition, Ferguson’s film draws on many experts who saw the crash coming, or speak to a culture on Wall Street that created the recklessness that led to the devastation.

In a particularly striking example of his argument, Ferguson begins the film with a direct analysis of the effects of the deregulation of banks in Iceland, serving as a microcosm of the financial crisis, in which the same kinds of behavior (excessive borrowing by banks, inflationary price increases in the housing market, and ballooning executive compensation) wrecked Iceland’s economy.

Though the complexity of the crisis is given close attention in Ferguson’s film, but ultimately, he succeeds in making it a story about a simple thing – human greed.

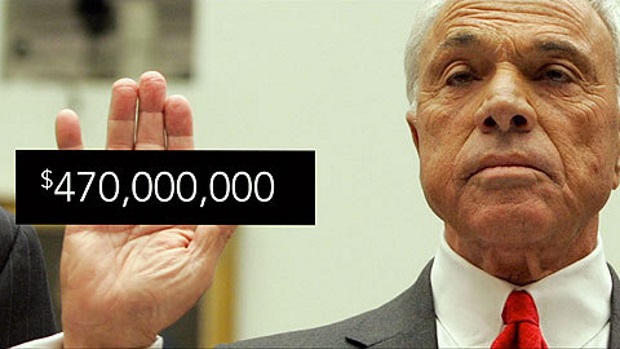

4. Margin Call (2011, Dir. JC Chandor)

Chandor’s debut film dramatizes and fictionalizes the last days inside an investment bank on the eve of the dawning financial crisis of 2008. Loosely based on Lehman Brothers, one of the banks to suffer the heaviest consequences in the crash (it was allowed to fail by the Treasury, and received no bailout money), the film covers one twenty-four hour period at the firm as the wheels start to come off of the world’s economic engine.

One of Chandor’s remarkable accomplishments is to create an entire class system of characters within the firm’s structure. From the lowest level analysts to the biggest board room executives, Chandor demonstrates the impact of the gathering storm on everyone who works at the bank.

Among the standouts are Zachary Quinto, playing a young desk jockey riding a Bloomberg terminal, Demi Moore as a token female executive who has learned to thicken her own skin, and Jeremy Irons as John Tuld (a stand-in for Lehman Brothers CEO Dick Fuld), the CEO who can’t quite believe the gravity of his situation.

Chandor’s script is highly engaging, accomplishing the daunting task that many movies set in the world of finance must, which is to explain the complexity of its characters’ environment in a way that feels organic and real, but also keeps the audience in the loop.

Chandor seems to have taken notes from Pakula’s depiction of board rooms and office hallways, which are rife with shadows (especially as the crisis appears to deepen and the outlook grows dimmer). Ultimately, what binds the characters together is their slow realization of just how bad the coming cataclysm is going to be.

5. Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps (2011, Dir. Oliver Stone)

Returning to the characters he chronicled in 1987’s original film, director Oliver Stone, no doubt infuriated by the financial crisis and what he viewed as the careless, reckless behavior of the banking executives he demonstrated no love for thirty years before, releases his former antagonist, Gordon Gekko, into the canyons of Wall Street just before the crash of 2008.

The film opens with a surrealistic credits sequence, tracking the path of several floating bubbles, paired with a voice over from Shia LaBeouf’s Jake Moore (taking over the hungry young wolf role from Charlie Sheen’s Bud Fox) explaining the concept of an inflationary market bubble, the phenomenon occurring in the housing market at the time the film is set.

The popping of that bubble, dramatized in the film, where housing prices collapsed as homeowners began to default on their mortgages, leaving investors who had bet on their security holding the bag, sets the stage for the film’s middle section, where Gekko, Moore, and the other fictional characters navigate their way through the smoldering wreckage of America’s economy.

Stone goes so far as to dramatize events reported to have taken place during the crisis lowest moments, including a meeting between the Treasury Secretary of the United States (unnamed in the film, but meant to represent Henry Paulson) and the banking executives of the major Wall Street banks, whom the Secretary must convince to accept bailout funds from the United States government in order to save the economy.

While the film loses some of the venomous bite of its predecessor, mostly by making Gekko a protagonist rather than the personification of greed he was in the original, it serves as an indictment of a system that Stone sees as more corrupt than one individual (Gekko) could ever have imagined.