Stanley Kubrick is one of the most well-known and well appreciated filmmakers in America’s history. His films have shaped and altered American cinema by pushing boundaries, breaking rules, and bringing a depth that most American filmmakers cannot bring to the table. In part, this success is due to Kubrick’s undeniable intellect and curiosity, and in part it is due to the timing of his work and the philosophical currents that have shaped our culture.

In what is to follow, I attempt to analyze the philosophical foci of Kubrick’s last 7 films. These are perhaps his more adventurous, and are certainly films which break the norms of cinema at the time by focusing on artistry more than dialog and by pushing censorship boundaries to drive his points home. Themes of postmodernism, obsession, dehumanization and the emptiness of human nature, and libertarianism pervade Kubrick’s oeuvre.

With that said, his works go beyond the typical classifications, phrases, and terminologies of most philosophical movements. This list attempts to do the same, by trying to capture the general philosophical characteristics of his last 7 films and not forcing them to fit into some philosophical category. It is my hope that this list will prompt you to watch his films or to see them in a way that you haven’t seen them before.

1. Dr. Strangelove or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

Dr. Strangelove is Kubrick’s great black comedy hit of 1964, a film which, during the height of the cold war, sought to parody life and use satire as a means to comment on war, genocide, and power. It takes place as a paranoid US General (Sterling Hayden) conspicuously named Jack D. Ripper launches a nuclear attack on the Soviet Union without all of the usual and appropriate approvals from his superiors.

Only he knows the codes to recall this great weapon of mass destruction, and unfortunately no one is able to get into contact with him. All the while, everyone (most notably a former Nazi scientist named Dr. Strangelove (Peter Sellers)) does everything in their power to avoid the ensuing nuclear holocaust that is sure to destroy the world.

You may wonder, “How can one mock nuclear holocaust without being brash, course, or even arrogant”? Kubrick’s mockery may be any of those things, but it is full of humorous and deep dialog. Perhaps the best illustration is a short conversation between the President (Peter Sellers) and General Buck (George Scott).

President: I will not go down in history as the greatest mass-murderer since Adolf Hitler.

General Buck: Perhaps it might be better, Mr. President, if you were more concerned with the American People than with your image in the history books.

It’s easy enough to see that Kubrick is hinting at the motives behind being a superpower and asserting one’s dominance over other countries. Interestingly enough, he’s also commenting on humanity, vanity, and what motivates those in powerful positions.

Most pointedly though, Kubrick has both the President and General ignore the fact that this bomb will kill hundreds of thousands of people, and he does this intentionally by having the President talk of being called a murderer as opposed to being responsible for the murders.

Thus, the film is about more than Foucaltian power dynamics, because it’s really about the fallen nature of man and his selfishness and vanity. A bleak outlook, to be sure.

2. 2001: A Space Odyssey

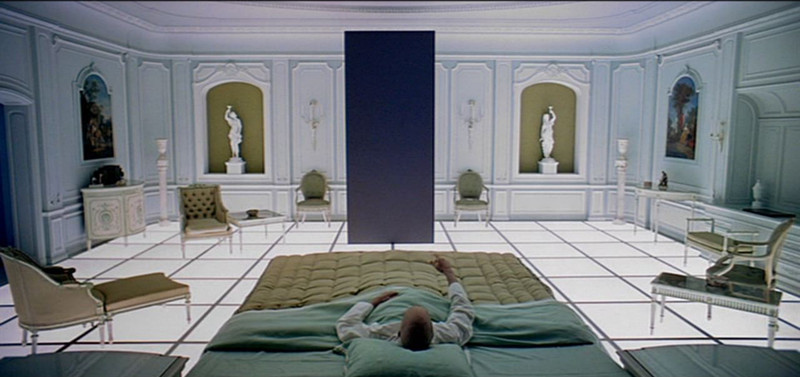

2001: A Space Odyssey is perhaps the most iconic American film of the 20th Century. Viewed by many to be Kubrick’s greatest work, it is an epic film following Dr. Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea), an astronaut attempting to understand a mysterious monolith that has appeared beneath the moon’s surface. It also prominently features H.A.L. 9000 (Douglas Rain), the artificially intelligent computer that is now so commonly alluded to in the arts.

The film deals with several issues, but in truth it never gives any conclusive answers to the questions it raises. Kubrick does not feign ignorance to these questions, but just hopes to leave the film open to interpretation.

Beautiful as the film is, both visually and audibly, I must admit I have always found its lack of clarity disappointing. Many theories have arisen that explain the monolith and the film’s mysterious ending, proving that Kubrick’s goal of having the film mean different things to different people has been achieved.

I interpret the film by placing it in a time of post-modernism in which it isn’t God that is dead, but rather it is the author that has moved on and refuses to comment (curiously, the one figure that could be interpreted to play God in the film doesn’t appear to be dead but rather seems to be entering the universe itself).

Perhaps it’s my subconscious speaking, but I can’t help but feel that Kubrick mocks post-modernism and relativism in 2001 (using post-modernism and relativism as his vehicle, no doubt) while flexing his incredible artistic prowess. In other words, it seems Kubrick is dissing relativism and saying that there are real absolute truths. Please, tell me in the comments why I’m wrong.

3. A Clockwork Orange

Much darker and more pointed, A Clockwork Orange followed 2001 and continued it perfect use of classical music to contribute to the mood, tone, and philosophical depth of Kubrick’s filmography. It follows Alex DeLarge (Malcom McDowell), a horrifying junior delinquent who terrorizes a futuristic Britain and eventually winds up serving some well-deserved hard time. While in prison, authorities subject Alex to various unique rehabilitative methods in hopes of accelerating his return to society.

Perhaps Kubrick’s most libertarian film, A Clockwork Orange is primarily intended to comment on the growing power of the state and how it can abuse its power intentionally and unintentionally. Clearly Alex needs some mental help in the film (though it is indeed questionable whether or not rehabilitation is even possible), but the state’s approach can only be characterized as heartless and cruel. After his treatment, Alex is hardly functional and severely handicapped.

That notwithstanding, he still acts unethically in seeking reparations. Perhaps Kubrick is saying that human nature is to some extent immutable, but it also seems like he’s saying the state is a blunt instrument utterly incapable of correcting man’s flaws. Clearly though, Kubrick is commenting on free will and how attempts to take away or reduce free will always fail and backfire.