In philosophy, one of the broadest interpretations of determinism is that all events and actions are externally causally predetermined regardless of human will, and hence are predictable in relation to their precedent external causes.

According to a number of religions, determinism is the doctrine that God foreknows all events that will happen, which are all predestined by him.

Hard determinists go so far to believe that not only is everything in the world predetermined, but it’s also subject to unmistakable laws, akin to laws of nature.

These laws govern our desires and drives, and live up to the prediction of our every human action and choice, stripping us of all free will, because though we have internal causes to do things, they are ultimately triggered by external causes in an almost infinite chain of causality.

And it’s that chain of causality that eventually shapes our human psychology, and therefore determines our human actions and influences our preferences and choices.

All of this could be traced back to the chain of causality, from our very human actions and choices to the very first big bang which initially started everything.

Compared to film theory, determinism in religion is similar to characterization in stories, in many ways. If determinism is God’s way of determining and destining who we are, then in writing it’s the screenwriter’s method of doing that to his characters.

When you characterize, you give birth to the character on paper and onscreen. You think of their back history, details of their past life, the circumstances they grew up in (“The Godfather”, “Braveheart”, “Forrest Gump”), or even conditions of their birth (“Million Dollar Baby”) that all will contribute to their actions and choices in life.

It’s about everything that would contribute to who they would live to become and how they would act under certain circumstances, so in characterization it’s more or less about causality.

Many great filmmakers, throughout the history of cinema, were obsessed with and concerned about the concept of psychological determinism, theological determinism, determinism vs. free will, and the human condition in the midst of all this.

They strove to explore these concepts and dilemmas in their films, some with a previous intention to prove a certain hypothesis, reject it, or implicitly provide answer an ultimate question. Some others have a mere passion for curiosity, provoking thought and discovering possibilities.

This article attempts to further analyze and read into some of the most remarkable films that most important brilliantly discussed, tackled, explored and provoked the world of determinism in their stories.

Spoiler Alert: Some major details in the listed films might be revealed in this article.

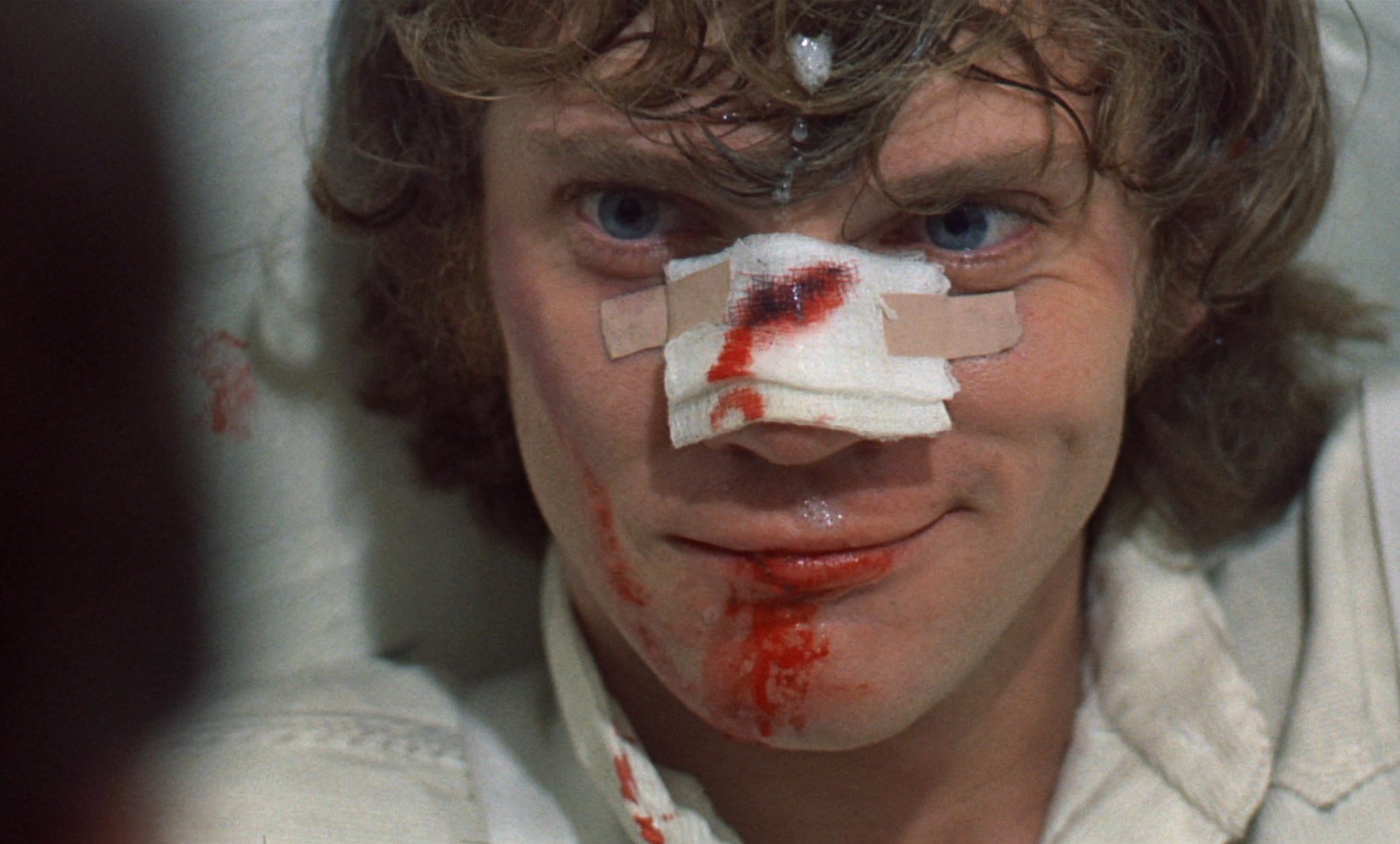

1. A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1971)

Set in a dystopian parallel future Britain, “A Clockwork Orange” follows the life of Alex DeLarge, a juvenile psychopath and sexual predator who is jailed after his accomplices conspire against him.

Alex is then voluntarily subjected to an experimental aversion therapy, with the anticipation of an early release in return. This therapy is meant to psychologically condition Alex against his own perversions, twisted desires and violent drives, in a set of aversive sessions that are expected to consequently turn him into an ideal and moral human being.

The Minister of the Interior arranges a demonstration to test the outcome of the authorities’ therapeutic corrective efforts to change Alex, during which he shows sickness to resorting to violence when he’s assaulted by a man, and shows surprising sickness to sex when he encounters a tempting nude woman.

The minister flaunts the fruit of his work in a round of applause, until the prison’s chaplain stands in protest, resenting the fact that a man was stripped off his free will, and that now, after this enforced conditioning, he wouldn’t be truly capable of making any moral choice, losing his essence as a human being.

There are so many contradicting messages and paradoxical questions that could be read in this scene. What is the definition of free will if Alex was previously still controlled by his psychological irrational drives and not his rational choices?

He was now operating deterministically, but at the end of the day he did choose to go through that aversive experiment hoping to change, yet eventually ceasing to be his original self, which almost cost him his life. Eventually, he was treated back into his old self.

The chaplain is superficially protesting for the sake of Alex’s free will, but that free will is questioned in the film in hard deterministic standards, because Alex, suggestively, didn’t have free will to begin with. And the efforts of changing his predetermined drives and psychology, in an attempt to fight his determinism, was another external cause to control his behavior, hence not resolving the free will crisis.

So what is the real answer to Alex’s crisis? Through the deterministic context of Alex’s world, the film simply stresses the dilemma without being obligated to provide an answer.

“A Clockwork Orange” was actually way ahead of its time in implicitly making a caustic commentary on all the sorts of aversive conditioning practices and efforts to control human behavior, most notable of which, those that were used in treatments of homosexuality and as a part of the overall efforts to control sexual orientation through the different practices of the notorious conversion therapy.

The aversion therapy used to control Alex’s sexual behavior and violent drives in “A Clockwork Orange” is akin to conversion therapy.

Alex’s condition is mysterious; he was not born in a bad environment or in hard living conditions that somehow contributed to shaping his psychopathic perverted character, therefore it’s suggestively implied that he’s delinquent either by deterministic nature, or due to the accumulative external deterministic influence of his society.

The film doesn’t provide an explicit answer for how was he forced into becoming what he is. Hence, it’s safe to say that “A Clockwork Orange” doesn’t go in the favor of a certain determinist hypothesis, or at the expense of another.

It’s rather a thoughtful journey in the world of futility and despair that is surrounded by the deterministic causality of society at large in a postmodern materialistic world that implicitly objectifies women and promotes perversions.

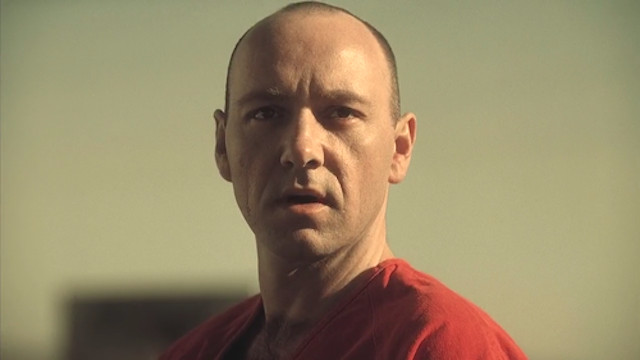

2. Se7en (David Fincher, 1995)

John Doe, the fanatic serial killer who carries out his symbolic murders as sermons to the world about the seven deadly sins, is precise, patient and very dedicated to his work.

Yet, why after masterminding all the murders, would he unexpectedly turn himself in, before finishing the two remaining sins, jeopardizing the completion of his horrific long-planned expressionist masterpiece?

In the finale of “Seven”, Doe leads the two detectives, Somerset (Morgan Freeman) and Mills (Brad Pitt), to what he claims to be the scene of his last crime. A crime that, we’re not aware, has actually yet to happen.

Upon the arrival, a revelation is made of “what’s in the box?” which exposes the murder of Mills’s wife by Doe out of “envy” (one of the two remaining sins). Mills’s role now in Doe’s masterful plan is to act according to his natural instinct, according to his inherent deadly sin. “Wrath”, which happens to be the last remaining sin in the seven after “envy”, and the two together form the missing parts of Doe’s unfinished masterpiece.

Mills consequently and unsurprisingly murders Doe as an act of revenge that is driven by his unforgiving “wrath”, finishing the sixth murder and becoming the living example of the seventh sin of “wrath”, for which he’s yet to be punished. In other words, He is actually the one who ultimately finishes Doe’s symbolic work.

Everything from the beginning of the story was a chain of causality that would determine Mills’s final act, including his sudden move into town, his involvement in the investigation, and his short temper that would lead him to unawaringly assaulting Doe at the scene of the third crime (Doe was then disguised as a photojournalist).

And then later, Doe sparing his life after cornering him at the end of the chase. All of this was leading up to Mills’s final destination, and to Doe’s choosing him to be a part of his act, in which Mills’s hands will inevitably be forced by a chain of causality. A theory that Doe successfully betted on with his life’s work, to conclude his shockingly traumatizing sermon, and prove his vision about humanity.

3. Dead Ringers (David Cronenberg, 1988 )

The story of “Dead Ringers” revolves around the relationship between two identical twin gynecologists, who are in fact far from being Identical when it comes to anything other than their looks. They act differently under similar circumstances; they show different preferences for women and sharply contrasting personalities, which is mysterious when we regard the fact that they both were created physically, mentally and biologically identical.

Yet, it’s explained from the very beginning by causality. The credits sequence at the beginning shows a pictorial representation of the twins in their mother’s womb, occupying different places in which each is positioned differently in a way that could possibly suggest that his journey into life, with all the small details of his birth, would play a strong part in deciding who he would grow up to become, regardless of sharing the same identical biology and identical mental capacities, which are perfectly illustrated in the twins’ equally high intelligence and masterfulness in gynecology.

4. The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980)

Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson), an aspiring writer and former teacher, moves into the isolated Overlook Hotel to serve, with his family’s company, as the new winter caretaker.

We’re informed earlier that Jack has had a small history of domestic violence with his son, which is associated with his previous alcoholism. Danny Torrance (Danny Lloyd), Jack’s son who was previously abused by him, has a talent for telepathic communication, ghost encountering, and experiencing visions of the past, which introduces him, prior to his parents, to the horrific truth of the Overlook Hotel.

Earlier, and upon arrival, Jack is warned that the previous caretaker had a claustrophobic reaction (cabin fever) that led him to a complete mental breakdown, that consequently led him to murder all three of his family members with an axe, a story that Jack sarcastically dismisses.

Over the course of a month, we observe Jack’s gradual descent into madness, or do we call it “evil possession”? The film provides evidence for both theories. Jack’s history with alcoholism and domestic violence could be an early clue to an anticipated future psychological relapse.

Yet, Danny and Wendy’s (Jack’s wife) encounters with ghosts, as well as Jack’s encounter with the former caretaker’s ghost, and his helping Jack to escape the storeroom, all are proof to the supernatural nature of Jack’s disintegration.

However, the two theories can still be simultaneously true, because determinism and the supernatural coincide in many doctrines such as religion.

5. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (Michel Gondry, 2004)

“Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” is a journey into the inter-related wondrous worlds of dreams, memories, and the human condition.

Joel Barish (Jim Carrey) and Clementine Kruczynski (Kate Winslet) coincidently meet on a Long Island train heading to Rockville center from Montauk, New York. They instantly communicate on many levels, subsequently starting what seems to be the potential for a promising relationship, which, they have yet to learn, is not their first to have.

As the major story events unfold, we start to realize how they used to be an affectionate couple in the past and each eventually resorted to a memory erasing procedure, as an aftermath of their deteriorating relationship and in order to get over one another, moving past what used to be a long, affectionate, and hard to forget love affair.

The film mostly takes place in Joel’s mind during the memory erasing procedure, and his later attempts to hinder and reverse the procedure after a change of heart, when he suddenly feels attached to his memories with Clementine.

His attempts all ultimately fail and he wakes up the next morning with no memory of Clementine, and with an unexplained immense will to go to Montauk, the last place that was mentioned by her in the last memory to be erased in the procedure.

We’re back at the first flash-forward scene in the film, with the two memory-erased lovers meeting on the train to Rockville center, and their chemistry is suddenly interrupted by the revelation of their previously erased love affair, which they learn about through one of victims of the procedure, who sends tapes of recorded sessions to both Joel and Clementine with each of them explaining their reasons for going through with the procedure and erasing each other.

The film narratively starts with its chronological ending to show us, when we finally get there again, how futile our efforts are to control our drives and affections, or choose who we love and who we don’t.

Upon the final revelation, the two characters ultimately choose to repeat the same experience they had all over again, despite of their mutual awareness of its likelihood to end the same way.