“Lars von Trier’s Breaking the Waves is a genuinely spiritual movie that asks ‘what is love and what is compassion?'”

– Martin Scorsese

In a broken dream

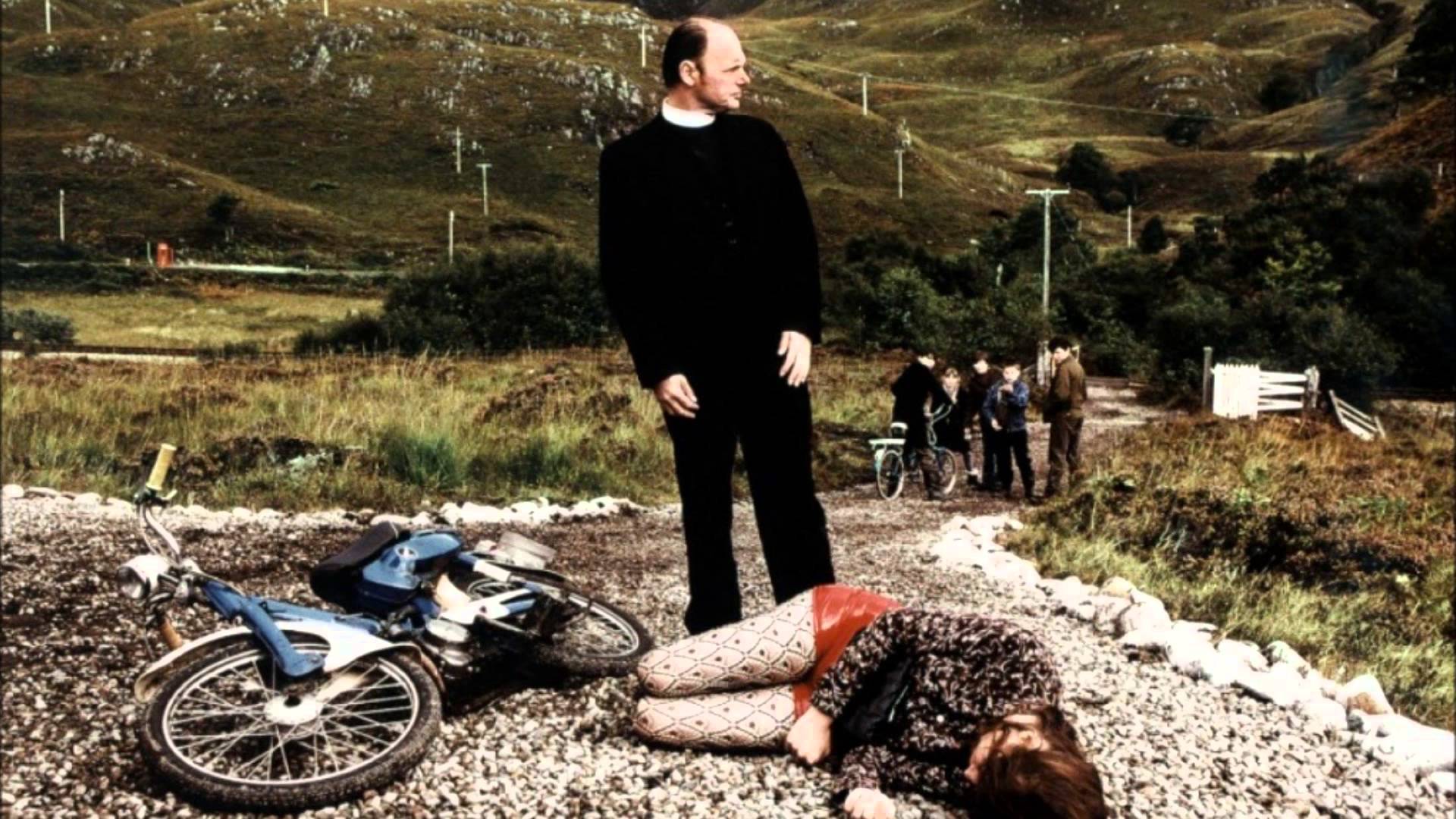

Set in remote North-West Scotland’s Outer Hebrides of the 1970s is the ill-at-ease and heart-rending romance of Lars von Trier’s paralyzing (and, alas, polarizing) melodrama, Breaking the Waves.

It is here that, in defiance from the dour Calvinist body politic in which she lives that Bess McNeill (Emily Watson, brilliant), a detached ingénue, begins to burgeon as her love for Jan Nyman (Stellan Skarsgård, superb), a Swedish oil-rig worker and athiest, manifests into marriage.

Certain that God gazes lovingly upon them, Bess’ new life is blissful and sacrosanct until Jan, working in the North Sea, is incapacitated in an industrial accident. Crippled and bedridden, Beth supplants her reserved religion with a fanatical love bordering on self-immolation in an all consuming conflagration that looks, from the outside, like sadistic sainthood.

Bess discovers that she can reach Jan by enumerating to him her sexual exploits. “I don’t make love with them,” Bess explains, “I make love with Jan and I save him from dying.” This tortuous zigzag experiment of love and faith at her husband’s charge is precarious and comes at a high price. Alternately comic, calamitous, and ruinous, Breaking the Waves is preternaturally vivid and, for better or worse, unforgettable.

“[Lars von Trier] makes us wonder what kinds of operas Nietzsche might have written. He finds the straight pure line through the heart of a story, and is not concerned with what cannot be known… Not many movies like this get made, because not many filmmakers are so bold, angry and defiant. Like many truly spiritual films, it will offend the Pharisees. Here we have a story that forces us to take sides, to ask what really is right and wrong in a universe that seems harsh and indifferent.”

– Roger Ebert

Goodbye yellow brick road

A saga-like work of histrionic artifice, Breaking the Waves is an epic of faith, love, martyrdom, and atonement. The film gains monstrous momentum and piercing power by the progressively ruthless, and shatteringly vicious events of the film’s final hour –– which includes Bess being almost supernaturally summoned out to sea by a cruel and sadistic sailor played by a menacing Udo Kier.

The plainspoken performances from the cast cannot be overlooked or undervalued. The late Katrin Cartlidge shines as Bess’ set upon sister, Dodo, and Phil McCall is alternately hilarious and horrible as Bess’ pietistic Calvinist grandfather. Much of the peripheral cast feel like an authentic collection of non-actors, and when combined with the deliberately low-res realist ‘Scope lensing of cinematographer du jour Robby Müller, the results are electrifying.

Müller, perhaps best known for his work with Wim Wenders and Jim Jarmusch, here takes many of his cues from von Trier’s Dogme 95 manifesto.

This “vow of chastity” was created by von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg, a fellow Dane who’s avant-garde approach to filmmaking focussed on traditional values of visual storytelling and a refusal to use special effects, post-production tweaks, or any reliance on gimmicks, sound effects, and so on.

True, Breaking the Waves was not a Dogme 95 film (CGI augmentation was used in the artful chapter breaks, for instance), but the urgency of the cinéma vérité style is almost cheerfully festooned with a reckless abandon. But this hand-held daring and frequent use of close-ups isn’t unjustified and it sharply adds a sense of intimacy and pathos that’s certainly one of the undeniable strengths of the film.

“Perhaps Breaking the Waves is my teenage rebellion.”

– Lars von Trier

Love is in everything

Drawing inspiration equally from Carl Theodor Dreyer –– his film Gertrud (1964) is in many ways Breaking the Waves’ template, but the cinematic portraiture and saintly suffering of The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) and the raw essentials of Ordet (1955) deserve mentioning as well –– and the Marquis de Sade’s 1791 novel, Justine.

Breaking the Waves was the first installment of von Trier’s “Golden Hearted Trilogy,” which is consumed and concerned with exploring the nature of love and sacrifice from a fearless female perspective. The other films in this thematic trey are The Idiots (1998) and Dancer in the Dark (2000).

Breaking the Waves came out after von Trier had completed his lengthy and pastiche-heavy Europa trilogy (1991’s Europa, 1987’s Epidemic, and 1984’s The Element of Crime) and was sandwiched between seasons 1 and 2 of his Danish TV miniseries, The Kingdom.

And while those projects were all venerated and highly praised, it’s fair to say that critics and audiences alike were not ready for the deeply-affecting, cold pack coup de grâce that Breaking the Waves was about to hand-carry directly to them.

Breaking the Waves took Grand Prix at the 1996 Cannes Film Festival, took the César Award for Best Foreign Film and garnered Emily Watson an Academy Award nomination for her efforts as well as marking a distinct and unequivocal artistic pivot for von Trier, establishing him as a serious artist and provocateur, full stop.

“For me, watching [Breaking the Waves] was like having someone walk over my grave. I could tell what was going to happen. Little things. I loved it, I found it very raw.”

– Emily Watson

Sing me to sleep

Righteously troubling, morally unpleasant, and yet unshakeably dazzling and full of grace, Breaking the Waves is an overwhelming and ecstatic experience. I’ll never forget my first viewing of the film; in a packed theater, minute by minute falling under its dark, somatic spell, becoming more and more involved, more and more imbued, and more and more lost to it.

Reverie and trepidation, I was swept up in something measureless –– that closing tableaux, was there ever so impressive and irrevocable a final curtain as this? –– I felt so forlorn and bone-weary when it past regret ended and the lights unhurriedly came up.

I’d been crying, and I knew that something in me had changed and I couldn’t articulate exactly how or precisely why, just that I was hit by a great intensity and a sorrowful sincerity. And also too I felt that, like Bess before me, I’d had some kind of tête-à-tête with a power greater than me.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.