“They Live is one of the best films of a fine American director.”

– Martin Scorsese

California Über Alles

In 1985 or thereabouts, around the time John Carpenter was taking a detour from his exploitation horror films to do the more family-friendly live-action cartoon Big Trouble in Little China, “The Master of Horror”––as he is often affectionately referred to––came upon an issue of a sci-fi anthology comic book called Alien Encounters.

This particular issue had a lively little entry written by Ray Nelson that had sprang from a short story he’d penned back in 1963 called “Eight O’Clock in the Morning.” The premise, that mankind was secretly being hypnotized and controlled by aliens, appealed to Carpenter straight away and he immediately optioned the film rights to both the comic and the short story and set about writing what would soon become They Live.

Exasperated, as so many Americans at that time were, by the Reagan Administration, Carpenter saw the potential in Nelson’s pulpy tale of alien sedition and chicanery for a satirical admonishing that would play to his many strengths as a genre director while digging his heels into the consumerism that the Teflon president so cherished.

Dressed in denim jeans, Ray-Bans, and sporting a now obsolescent mullet, They Live was destined for forcible greatness, counterculture efficacy, and cult adoration.

“They Live is best described as a brutally serious farce, a Marx Brothers comedy approved by Karl Marx.”

– Darrin Franich, Entertainment Weekly

Reagan is for the rich man

Wearing its B-movie designation like a merit badge, They Live was a droll, violent, sardonic, and deeply satisfying sci-fi action thriller. Cleverly obscured in its studiously trashy façade and buried deeply within its memorably awesome one-liners was a perversive and winking word to the wise.

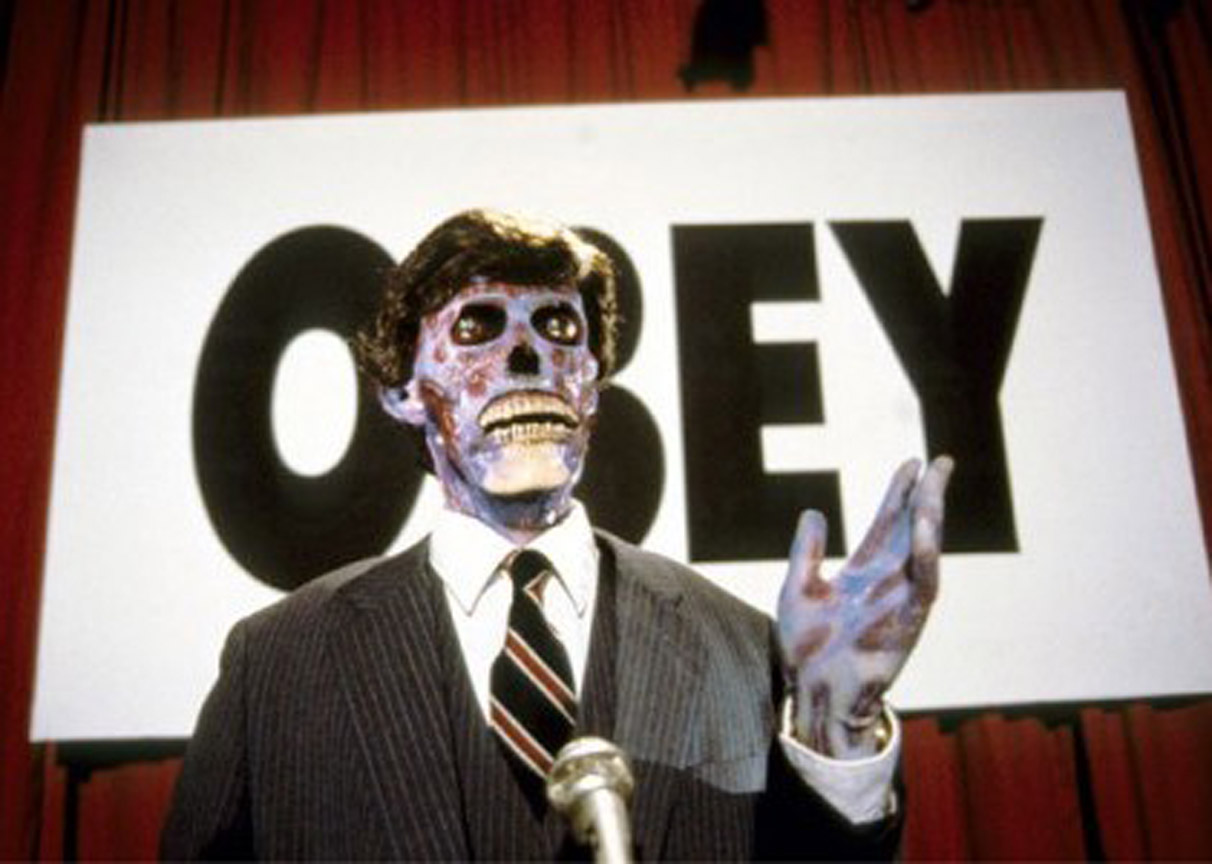

They Live’s premise is a straightforward one: John Nada (Roddy Piper) is an unemployed drifter with a very blue collar background who stumbles upon a pair of sunglasses that endow the wearer to see the truth: that aliens are using subliminal messages in our media to control us.

Only with the sunglasses on is their spell broken and the true messages of the mass cult apparent as when John sees that dollar bills suddenly read “THIS IS YOUR GOD”––the Almighty Dollar adage suddenly has spurs. The aliens walk amongst us, passed off as supervisors, yuppies, celebrities, and other people of power and influence. As their quarry we’ve been duped into complacency and servitude.

Set in the urban sprawl and the down-at-the-heel hemline of Los Angeles, the unconscious masses are so easily exploited, distracted, and steered. John, who soon aligns with rebels––those who manufactured the sunglasses he discovered––has the potential to become a reluctant working class hero, but many obstacles will slow him down, and he has every right to be overly suspicious of everyone.

“I have come here to chew bubblegum and kick ass, and I’m all out of bubblegum.”

– John Nada (played by Roddy Piper)

Don’t masquerade with the guy in shades, oh no

“They Live is definitely one of the forgotten masterpieces of the Hollywood Left,” says Slovene psychoanalytic philosopher Slavoj Žižek in Sophie Fiennes’ award-winning 2012 documentary, The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology. “The sunglasses function like a critique of ideology,” elaborates Žižek, “They allow you to see the real message beneath all the propaganda, glitz, posters and so on. … When you put the sunglasses on you see the dictatorship in democracy, the invisible order which sustains your apparent freedom.”

Carpenter’s film, years after its release, would also have an impact with influential skateboarding street artist Shepard Fairey, whose world renowned “OBEY” campaign, itself an experiment in phenomenology, was directly inspired by the film. “[They Live] has a very strong message about the power of commercialism and the way that people are manipulated by advertising,” says Fairey.

“[John Carpenter’s] pictures always have a handmade quality—every cut, every move, every choice of framing and camera movement, not to mention every note of music (he composes his own scores) feels like it has been composed or placed by the filmmaker himself. His sense of composition (nearly all of his pictures are shot in Scope) is quite exacting and precise, and his control of movement inside and outside the frame can be hair-raising… [They Live] is lyrical and tough at the same time.”

– Martin Scorsese

We’ve got a bigger problem now

As a standard-bearer, John Nada’s plebian status makes him easy to root for, but his inability to come up with a clever plan to combat our alien overlords combined with the brilliant casting coup of professional wrestler “Rowdy” Roddy Piper in the part, works astonishingly and surprisingly well.

John’s instincts after wearing the glasses and seeing the skeletal alien despots in our midst is to basically start calling them out and throwing punches. Ditto when he tries to convince one of his few pals and construction site co-worker Frank Armitage (Keith David) to try on a pair of glasses and see the conspiracy for himself. So inept at using a verbal strategy to convince Frank to don the shades for one hot minute the scene transgresses into a confrontation so savage and protracted that it’s regularly cited as one of the lengthiest fight scenes in cinema history.

Darren Aronofsky was deeply inspired by John and Frank’s neverending pummeling and it helped shape many of the visceral fight scenes in his harrowing 2008 sports drama The Wrestler. “I think that with They Live John Carpenter was trying to lampoon fight scenes as, you know, they were clearly fake,” Aronofsky told Time Out, adding: “People in that bloodthirsty world [hardcore wrestling] are looking for men and women who risk themselves and their health by doing more and more dangerous stunts. In They Live – it’s not about who wins; it’s about how much can people hurt each other.”

Carpenter has also said many times over the years that the epic bell-ringer between Piper and David’s characters was intended as an homage to John Ford’s 1952 film The Quiet Man, where John Wayne and Victor McLaglen comically and extendedly duke it out.

“In France, I’m an auteur; in Germany, a filmmaker; in Britain, a genre film director; and in the USA, a bum.”

– John Carpenter

This is your god

The crumbling America of They Live shows a poverty-addled country with a colossal gap between the rich and the poor. The homeless population is waxing and an increasingly violent police presence rides roughshod over them as blackhearted billboards seem to chaperon their downthrow.

Carpenter creates shocking and indelible tableau regularly in They Live’s nimble 94 minutes––a shanty town shakedown at night with bulldozers and militarized law enforcement is rattling––and his endless editorial of the Reagan-era’s empty articles of faith and anti-consumerism is pretty awesome.

Carpenter’s films are seldom ever so pedantic and this makes They Live all the more provocative. Sure, the film is intellectually incoherent at times, there are plot holes big enough for a Mac truck to jackknife through, but that doesn’t make it any less enjoyable or fist-pumping. It’s easy to forgive some self-contradictory embellishments and untenable twists in a film that never tries to revoke its B-movie mindset. This is a film you’ve got to love warts and all or else maybe not at all.

Don’t let the writing credit for They Live fool you, Carpenter wrote the screenplay using the nom de plume “Frank Armitage” (the name is an homage to H.P. Lovecraft––and if you doubt his love for Lovecraft may I direct your attention to his overlooked horror masterpiece from 1994, In the Mouth of Madness). Carpenter, as he often does, also delivered a bluesy, bullet’s-sweating score for the film that ranks as one of his most intermittently memorable and morose.

It’s rare, in my estimation, that a film as gloriously loopy as They Live can still be so engaging, which is certainly a testament to Carpenter’s ingenuity and forceful vision. The more self-indulgent it becomes, which is incredibly, the goofier and more strangely sublime it becomes, too. Strikingly subversive, perversely playful, and furiously funny, They Live takes a paranoid bum trip and turns it into an exuberant accomplishment.

“You ain’t the first son of a bitch to wake up out of their dream,” a weary John spits out to frustrated Frank. Oh we know, John. We know.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.