Film has long been the best medium for comedy, tragedy, and philosophical art. One might think it would be a great place for theology, too. More often than not, “Christian films” are neither Christian or films, but rather serve to hype up the base and whisper sweet nothings into the ears of those already on board with their message.

I have been disappointed with the film industry’s portrayal of theology and philosophy for some time, so much so that I decided to rectify that myself (to learn more about me and my project, go here) with a comedy about a man’s struggle against God. If you have liked (or hated) my writings in the past, here’s a good opportunity to help me make something more personal so that you can enjoy (or mock) it more freely.

That notwithstanding, there are a number of less-known theological films that are underappreciated and rarely talked about by mainstream moviegoers. This list is not comprehensive, but is rather a selection of 10 great theological films, chosen for their quality as a film, and not as an educational tool for teaching doctrine.

If you’re interested in theology, the Judeo-Christian tradition, or just religious art, you should see these films. I have limited my choices to 1 per director, so please understand that the list is not all Malick and Bergman. Disagree with my choices? Yeah, I’m sure you do. Tell me why in the comments.

10. Babbette’s Feast (1987, Gabriel Axel)

Babbette’s Feast is an unusual Danish film about the servitude of Babette (Stephane Audran), a young woman who helps care for two middle aged Protestant sisters in Jutland. Babette is a refugee from France and has served the women for 14 dependable years before the film takes place, and through flashbacks we learn about the sisters and their past.

Interestingly, little is ever revealed about Babette and her past, though it is clear she has been a good and faithful servant. One day Babette wins the lottery and, instead of leaving her life of servitude, she decides to give back to those who have given her so much by cooking a lavish French dinner for them and their guests.

The film is explicitly religious as it deals with the faith of these two devout sisters and as Babette stands in for Christ, who prepares and blesses the final meal for his disciples. Still yet, the film’s theology is deeper than that, subtly drawing a distinction between the needs of the spirit and the needs of the flesh. The sisters live a plain and simple lifestyle, while Babette’s cooking is lavish, extravagant, and expensive.

Naturally, these pious women object to spending so much on a meal and to the over-the-top presentation of it, but they miss the point that Babette is cooking for their soul and not for their bodies. Food and many, many other things have deeper impacts than our physiological needs. “Taste and see the goodness of the Lord.”

9. A Serious Man (2009, Joel Coen & Ethan Coen)

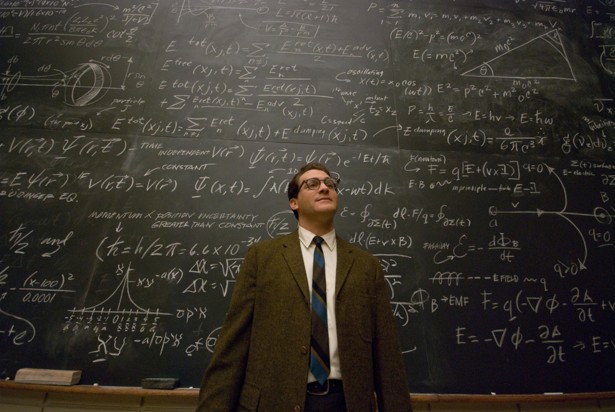

A Serious Man is the darker, more comedic version of The Tree of Life, made by the ever hilarious and talented Coen brothers. It follows Larry Gopnik (Michael Stuhlbarg), a professor wasting away at a small school in the Midwest, whose wife is trying to leave him.

Despite pretty much everything going wrong in his life (from his job and tenure track to his son’s behavior), Larry is a good man who tries to remain faithful to God and be patient with life. At the beginning of the film, we see that Larry and his family are cursed because of the mistakes of his ancestors, calling into question everything that is about to take place.

The central question of the film is that of the silence of God. Poor Larry deals with tragedy after tragedy and tries to consult his rabbi and spiritual leaders. Unable to even get through to them, he asks everyone around him why such evil keeps happening. He calls out to God and gets no response. Like Bergman, Malick, and many others, the Coen’s really emphasize this, using a number of different subtle techniques to show just how alone Larry is.

The film isn’t so much about whether or not one can have faith in the face of such adversity, for Larry surely does. Rather, the Coens ask whether or not one should. The ending of the film shows that it isn’t God that needs us, but rather we that need him. Larry’s situation is clearly out of his control, so what does having faith cost him?

8. Ida (2013, Paweł Pawlikowski)

Ida is a new polish film following a young woman, Ida (Agata Trzebucowska), as she prepares to take her vows to be a nun. Unlike Bunuel’s Viridiana or other films on the topic, Ida explores the differences between Catholicism and Judaism in a post-WWII Poland that looks and feels like the dark and disturbed setting one would expect after the Holocaust. Beautifully shot in black and white, and with superb performances from the entire cast, it’s a rare masterpiece of the last few years.

Before taking her vows, Ida visits her aunt, Wanda (Agata Kulesza), who is also her last surviving relative. A bit of a train wreck, Wanda tries to lead Ida astray, begging her to sin a little and therefore live a little before she commits her life to God. She also informs Ida that, although she was raised by the convent after her parents’ deaths, she is actually Jewish and her parents were devout Jews killed by the Nazis near the end of the war.

Wanda plays this up a lot, really more than she should, and begs Ida to consider what it means to be a Catholic nun given her heritage. “The house will be divided…mother against daughter and daughter against mother.”

7. The Decalogue (1989, Krzysztof Kieślowski)

Although not a traditional film, I had to cheat and include Kieslowski’s The Decalogue, a 10-part mini-series exploring the laws of the 10 commandments. The series is cohesive in that all the episodes take place in the same building in Poland, and in that one actor reappears in several episodes (8 out of 10) as an observer of mankind and his failures, yet each episode shows Kieslowki’s take on a different topic.

The episodes are powerful because, unlike your average film on the 10 commandments, Kieslowski’s filmmaking is plot driven and subtle. The characters in The Decalogue are normal people faced with situational ethics. They don’t philosophize about the law or go on diatribes about the ethical way to behave, but rather live out their decisions and face the consequences.

In Decalogue 2, for example, a woman tries to find out if and when her sick husband will pass, because she is secretly carrying the child from another man. She plans to abort the baby if her husband will live, and to give birth if her husband is going to die. That isn’t the stuff of your typical ethics thought experiment, but is more raw and gritty.

The Decalogue does not examine the 10 commandments for what they were when they were handed down to Moses, but rather asks its viewers to examine themselves and evaluate if they are living a sinless life.

6. Au Hasard Balthazar (1966, Robert Bresson)

Au Hasard Balthazar is a Bresson masterpiece about Balthazar, a saintly donkey who is abused and exploited throughout his life, and his relationship with Marie (Anne Wiazemsky), a young lady struggling to survive in rural France. Both Marie and Balthazar are abused and face extreme hardships, but Marie loses her faith in God over time, questioning why she continues to face hardship.

Rooted in her faith, she is never able to completely turn her back on Christianity, but trials and troubles increase her doubts. Conversely, Balthazar remains faithful (even stubborn) and never turns his back on his owners, despite all the situations in which it would make sense for him to leave or escape. Bresson depicts Balthazar as the saint, and uses his story to explain that suffering is necessary and can be good.

In this sense, Balthazar takes on the form of so many martyrs and saints from before. We see him mistreated, beaten, rejected, and outcast repeatedly, until his symbolic death. Before he passes, Balthazar sees sheep in the distance, which come and surround him, comforting him. In a sense, the scene creates a feeling of “too little, too late”, but that misses the point of the entire film.

These sheep come to carry saintly Balthazar to the bosom of Abraham, just like Lazarus was carried away by angels of mercy. Bresson does not tell us via dialog or voiceover what his films are about, but rather focuses on the image, on objects, and on beings. His depiction of Balthazar, a donkey, as a saint is certainly unique, but that makes it all the more powerful, as it reminds us that godliness can be recognized and emulated by everyone.