Thomas H. Ince was responsible to conceive the production system adopted by Hollywood during its Golden Age. In 1912, “Inceville” was the first studio to test the following filmmaking method: a number of production units, each headed by a director, who had the responsibility of supervising a team of writers who delivered shooting scripts to their boss – Ince – and upon his approval, worked in collaboration with him to lay out the film shot by shot. Then, as a sort of car part in a Ford’s assembly line, the film would be shot within days, edited and ready to meet the audiences.

This model was also applied in the Triangle Film Corporation, a partnership between Ince, D. W. Griffith and Mack Sennett. And this aspect became vital, for once the company began having problems and each partner followed his own path, this model was applied into other film studios developed by the three men, with particular focus on the Keystone Film Company.

Keystone was owned by Mack Sennett, to many unknown, to others known as the father of silent comedy. During the period of 1913 – 1935 Keystone produced a great number of “two reelers” (short films) and features films that were responsible for the birth and consolidation of slapstick comedy that often worked as a parody of more “serious” films such as Griffith’s.

Through Sennett’s hand a number of people became Hollywood stars. People like Roscoe ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle, Mabel Normand, Gloria Swanson, Charles Chaplin, Frank Capra, Carole Lombard. Names (with the exception of Fatty) that later diverge their own ways into the major studios. Which already existed in the decade of 1910.

In the 1910s, American cinema, which was already exploring a new range of film genres like action, adventure, drama or fantasy films, was organized in Three Industry Giants: Paramount Pictures, Lowe’s Inc. (later became MGM) and First National Pictures. Which controlled both production and distribution of films, as well as, theatre chains where they would be exhibited. For its competitors, “The Big Three” had: Fox Film, Universal and Keystone, which operated in similar concepts yet with lesser funds.

Below this line, operated minor studios such as Columbia (which later became a major studio), Republic or Monogram that became part of what in the 1920s became known as the “poverty row”, a group of small studios responsible for producing B pictures.

This was the state of the film industry when Chaplin and Keaton began their careers somewhat around the 1910s.

The Comedy style of Charles Chaplin

Charles Chaplin, whose parents were humble musical hall entertainers in London, had a difficult deprived childhood and recurred to the stage – at the age of 9 – in order to support himself once his mother felt mentally ill and his father failed with his parental obligations.

During his teenage years, Chaplin worked for several travelling vaudeville shows and managed to participate in theatre productions that toured all over the country, as well as, abroad. With one of those companies, Chaplin embarked on a tour to America and there he was offered a contract with Mack Sennett’s Keystone Film. The year was 1913.

In 1915, Chaplin signed a contract with Essanay Films which provided him with full artistic control over his projects. The most remarkable being “The Tramp”, “Work” or “A Night at the Show”. In 1916, while fulfilling a new contract with Mutual Film, Chaplin successfully worked on films like “One A. M” (1916), “The Pawnshop” (1916) and “The Immigrant” (1917).

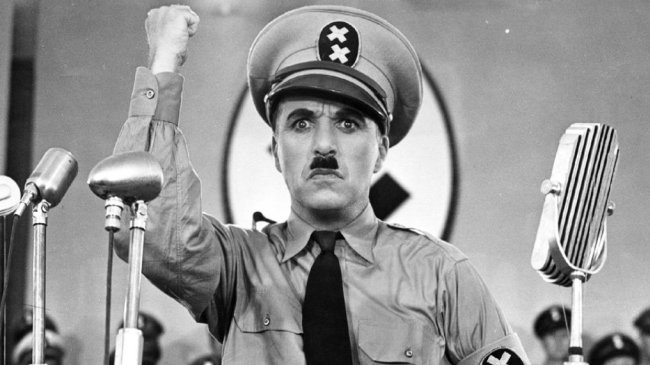

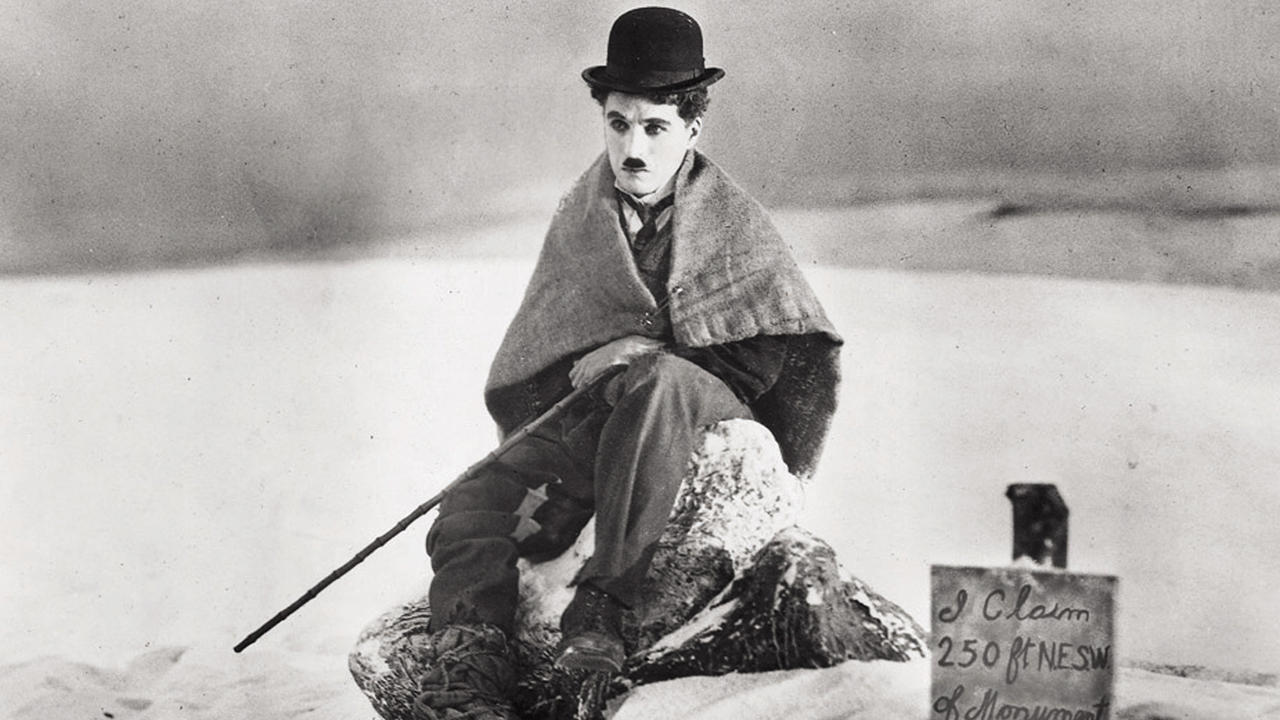

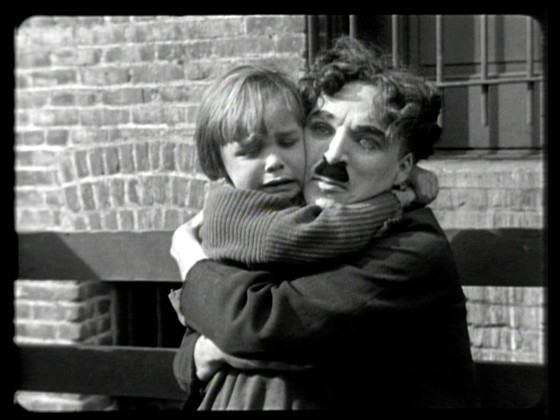

However, 1918 was his most profitable year once he signed a million-dollar contract with First National Pictures, for which he directed films like “A Dog’s Life” (1918), “The Idle Class” and “The Kid” (1921) or “Pay Day” (1922). Furthermore, this contract allowed Chaplin to establish his own studios where he directed most of his later films some released through United Artists (which he founded in 1919 with D. W. Griffith, Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford), such as “Gold Rush” (1925), “City Lights” (1931) or “The Great Dictator” (1940).

The paranoia that followed WWII, caused troubles to Chaplin in America, particularly with the FBI and the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), ultimately leading to his exile in Switzerland where he lived until his death in 1977.

His last films were “Limelight” (1952), “A King in New York” (1957) and “A Countess from Hong Kong” (1967).

1. Intelligent and restrained use of the Slapstick elements

The films produced by Keystone were responsible for the birth of Slapstick comedy. These films, borrowing techniques from vaudeville and musical hall numbers, exaggerated in physical comedy and frequently used a number of recognizable elements such as throwing pies, poking the eyes, falling, chasing, etc.

Even though in the beginning of his career, Chaplin worked on a number of slapstick comedies, while developing his own style he left aside some of this basic slapstick elements and decided to develop the narrative complexity of his films by exploring the effect they had over the audience, as well as, developing ideas behind flat comedy just for the show.

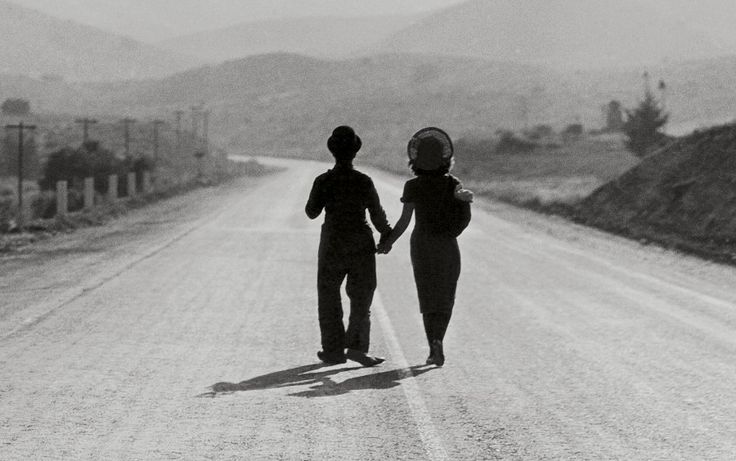

And this is the reason why after his period in Keystone, the comedy master started developing a character “the little tramp” which would become a symbol of Chaplin’s comedy style.

2. Social Satire

Because Chaplin lived an impoverish childhood with great difficulties, he always felt keen towards the underprivileged and this became an essential trace in his comedy, as well as, in the films he developed – from the biographical “The Kid” in 1921 to the great final speech in “The Great Dictator” in 1940 or through the characters of Monsieur Verdoux (who commits crimes in order to support his ill wife and young son) and Calvero (who does everything he can to aid the ruined Thereza).

However, Chaplin’s satire doesn’t come only from the characters but also from situations that reflect the values society lived and still lives for – the essence of its ‘rottenness’. Blindness and greed in “The Gold Rush” (1925), consumerism and the essence of America’s Golden Twenties in “City Lights” (1931) and “Modern Times” (1936) or hypocrisy in “Monsieur Verdoux” (1947).

3. The introduction and use of Pathos

Pathos or the appeal to emotion was introduced in comedy via Charles Chaplin. And many historians have claim “The Tramp” (1915) as one of the first examples of putting emotion in comedy, particularly, in a scene where the tramp gets shot by a farmer and instead of using this to introduce yet another gag, Chaplin chooses to have the tramp really hurt and showing pain which made audiences feel pity and sorry for Chaplin’s character.

Also noted is the introduction of morality in comedy of which “The Tramp” is also a pioneer at, since in this film the little tramp returns the stolen money to its rightful owner, thus, showing moral integrity.

4. Visual simplicity

In his autobiography Chaplin wrote “Simplicity is best…pompous effects slow up action, are boring and unpleasant…the camera should not intrude”. This sentence sums up Chaplin’s philosophy when it came to shooting and this is also connected with his creative process.

Since Chaplin improvised in many of his films, the adding of unexpected elements such as a fall or a gag with an object of some kind had to assume that the camera should be there to capture it. Not to move around it or capture the action from different angles just capture it. Therefore, one must assume Chaplin’s visual style as coherent, simple and sharp. In which the camera should be unconsciously present.

This reveals yet another distinctive trace in Chaplin’s style, he understood the emotional potential of film and its mechanics and used it to reach audiences, whereas, for instance, Keaton used this knowledge of the mechanics of film to build complex visuals and intricate narrative-gag sequences.

So, naturally, editing comes as another element in which both diverge. Chaplin used editing to achieve a visual perfection and precision in terms of rhythm while putting a clear emphasis on pathos and in the depth of scenes.

More in Chaplin than in Keaton, editing achieved an extreme importance. Since Chaplin improvised a lot, editing was more than just the moment where the film was put together, it was the moment where all the apparent loose scenes he had shot were assembled into one piece – a film.

Therefore, editing was the stage in which the film’s rhythm was really defined for Chaplin, because, unlike Keaton who worked with a team of small collaborators who used to draw an idea of the story before filming, Chaplin worked without a script.

5. Distinctive production system

Chaplin should come in the dictionaries as the synonym of one man show. ‘The little tramp’ was a really gifted artist who learned by himself many important notions when it comes to performance and film. Chaplin had an intricate knowledge of how to express himself through body motion and the importance of the body in performance.

Chaplin also learned and was a pioneer in exploring film as a vehicle. A vehicle for different types of comedy, for emotion, for ideas and for channeling a message. All this he learned from experience, and mostly, by himself. Facts that made him want to control every aspect of his films.

Contrary to Buster Keaton, Chaplin worked around unscripted stories and, thus, his storytelling process was based solely on improvisation. On this subject PBS describes Chaplin’s shooting process writing: “He shot and printed hundreds of takes when making a movie, each one a little experimental variation.

While this method was unorthodox, because of the expense and inefficiency, it provided lively and spontaneous footage. Taking what he learned from the footage, Chaplin would often completely reorganize a scene. It was not uncommon for him to decide half-way through a film that an actor wasn’t working and start over with someone new. Many actors found the constant takes and uncertainty gruelling, but always went along because they knew they were working for a master.”

Chaplin also had a restrict number of faithful collaborators, that can be reduced mostly to one person, his cameraman Roland Totheroh. This was due to the fact that films really absorbed all his energy and, thus, when shooting a film, he became a moody, unstable person which lead to a number of conflicts with crew workers and actors (famously with his third wife Paulette Goddard in the set of “The Great Dictator” in 1940 which lead to their divorce). Chaplin also had a preference for shooting in studio because it provided him with an environment where he be in control of everything.

For more information on this topic, a great source is the documentary “Unknown Chaplin” (1983).