This year will mark the 88th time the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has given out it annual awards (somewhat affectionately known as Oscar, though why is veiled in mystery).

Oscar has its proponents but also its critics. For every fans/critic/historian who may look to the little golden statuette as some mark of quality in motion pictures there is least another person in one or more of those categories who insist that its nothing but a business/financial/industrial political tool of no artistic merit.

There are many lists on many sites which attempt to show that Oscar plain doesn’t known anything and almost always gets it wrong (and, make no mistake, the Academy has given plenty of ammo to the enemies).

This is not really one of those lists. Instead, the following list wishes to point out some of the award’s more….well, unique moments. In nearly 90 years there have been an abundance of moments of all kinds. Here then, are some of Oscar’s more singular instances.

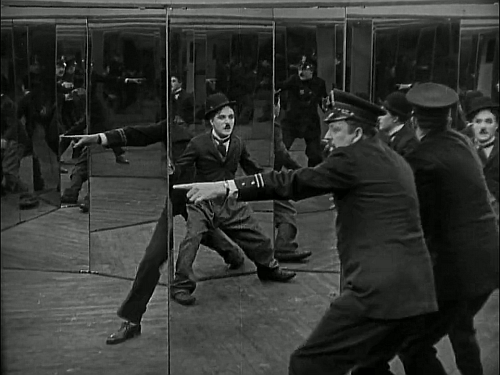

1. Charlie Chaplin get wiped away (best actor and best comedy director, The Circus, 1927-1928)

Oscar’s odd ways started right at the beginning. But for a rather strange decision, Charles Chaplin, one of the seminal figures in motion picture history, would have gone home from the first Academy Awards a double winner.

That year he was nominated for both acting in and directing The Circus (that year the Academy oddly gave out separate awards for directing dramatic films and comedic ones).

The new organization decided that was too much virtuosity and rather arbitrarily declared Chaplin ineligible for those awards, choosing instead to give him a special award. Huh? The voting record, public in the organization’s early years, shows that German actor Emil Jannings and Two Arabian Knights’ director Lewis Milestone, the eventual winners, should have been glad for the fact.

Sadly, this set the tone for Chaplin’s history with the Academy. His only other acting nomination was for 1940’s The Great Dictator, writing noms for that film and 1947’s Monsieur Verdoux (which contains possibly his finest acting work), and a most unusual Oscar win (more on that later).

Near the end of Chaplin’s long life, the Academy gave him another honorary award (to make up for much more than its own treatment of him). Too bad that they just didn’t do the right thing way back when.

2. Who’s on first? (1927-28)

Chaplin’s removal wasn’t the only oddity that first Oscar year. To this day official Academy records list the 1928 aerial war-action film Wings as the first Best Picture. This is true enough, as far as it goes, but not quite the complete story.

Also listed in the Academy records is an award for “most artistic quality of production” and that went to the F.W. Murnau’s exquisite late silent classic Sunrise. In point of fact, Wings, award was really for “best overall quality of production”. Actually there was no Best Picture as such.

Sunrise could be just as justifiably considered the first Oscar winner for best picture as Wings. The strange thing is that Wings, though rousing, is very much a product of its time (and more than a bit sentimental in a masculine sort of way). Sunrise, on the other hand, was, and still is, considered a great artistic achievement, the sort of film the Academy claims to have originally set out to honor.

There may be another factor in that Wings was a big box office hit and the prestigious Sunrise, which cost a fortune to make, wasn’t. Isn’t it strange that the group has stuck with the big commercial hit?

3. Jeanne Eagles blazes a trail none would wish to follow (1928-1929)

The second year of Oscar saw something happen that is sadly not unique. Academy co-founder Mary Pickford, as seminal screen figure as Chaplin, made her pretty unsuccessful talkie debut in Coquette (1929), giving an awkward performance in a now very dated version of a then hit play. She called the then small board of the Academy to her lofty estate Pickfair and more or less told them to give her the next Best Actress award…which they did.

Yes, someone got gypped but the most deserving actress on the nominated list (to modern eyes certainly) didn’t mind as she was too busy being dead. Jeanne Eagles was a legendary stage actress, even in her own turbulent time on earth.

Best remembered for originating the role of Sadie Thompson in the first Broadway production of Somerset Maugham’s Rain, she was equally infamous for her excessive living, including much, much substance abuse and loads of irresponsible behavior to match. Like most stage performers of any stature in her day, she disdained working in movies after trying films a while during the World War I era and not liking the results.

Unfortunately, her behavior (especially not showing for performances and giving no notice beforehand) had gotten her banned from the stage by Actor’s Equity. Thus she took the movies up on offers starting at the end of the silent era. She was nominated for her talkie debut, 1929’s The Letter, an adaptation of another Maugham story.

Made at Paramount’s somewhat technically backward Astoria, Long Island New York studio, this tale of adultery and murder in Maylasia turned out to be, well, an awful film (look to the classic 1940 remake from Eagles’ great fan Bette Davis and director William Wyler to see how it should have been done). However, Eagles was superb (save for the badly written murder scene).

However, her habits, including Heroin use, were catching up with her. After making one more film, she died of an overdose of several substances. Be that as it may, the Academy did make her the first of a rather small handful of posthumous nominees but left it at that.

4. Twice as nice (1929-1930)

The third year of the Academy saw a strange and understandably short lived change in the proceedings. The first year the group had allowed performers and others to be nominated for their body of work rather than one film (a good idea, still followed by the New York Film Critics award). The next year saw nominations for just one film per nominee. Then the third year the group had a sort of change of heart.

Actors and directors could receive two nominations if they had done more than one film during that period (and the early years went by theatrical seasons, not calendar years). Thus most of the acting and directing nominees ended up with two nominations apiece. The winners, stage star George Arliss for Disraeli and MGM queen Norma Shearer of The Divorcee were also nominated for The Green Goddess and Their Own Desire.

Arliss competed with Ronald Colman for his first two talkies, Condemned and Bulldog Drummond and French star Maurice Chevalier for his first two US films, The Love Parade and The Big Pond, while Shearer, with the help of her powerful husband Irving Thalberg and the MGM front office, battled off her fellow MGM-er, the great Greta Garbo for her first two talkies, Anna Christie and Romance (and Garbo’s director in those films, Clarence Brown was a double-dipper as well).

The weird thing is that Academy records indicate that only one film would end up being determined to be the “real” nominee by a process the organization neglected to write down for posterity. So, were Colman and Garbo three or four time career nominees? Shearer five or six? Who can say?

5. Youth on Parade (1930-1931)

The Academy has had a most serpentine relationship with younger actors. Some (many) think that putting children in a contest with adults is quite cruel and they may well have a point.

From the mid-1930s until 1960 the Academy gave out a dozen special Oscars for juvenile performers and such bright little lights as Shirley Temple, Judy Garland, Deanna Durbin, Mickey Rooney (who, typically, didn’t collect his as he thought of himself as more than juvenile and, indeed, won his first competitive Oscar nom the very next year), and Margaret O’Brien received those miniature satuettes.

Walt Disney got the group to dust it off one last time for his Pollyanna star Haley Mills after younger performers had already started being nominated along with adults (notably Brandon de Wilde for Shane in 1953 and Patty McCormick as a child murderess in 1957’s The Bad Seed). Most of the nominees have been young ladies and most in the supporting categories.

The youngest best actress nominees were 13 year old Keisha Castle-Hughes for Whale Rider in 2002 and 9 year old Quvenzhané Wallis, a non-professional, for 2002’s Beasts of the Southern Wild. However, there has only ever been one child performer nominated in the best actor category, also at 9 years of age, and he was a true child star.

Jackie Cooper was the big kid star in Hollywood until the arrival of Shirley Temple. He started his climb to stardom as one of the lead kids in the famed Our Gang shorts and that’s significant since Skippy (1931), the vehicle that pushed him to stardom plays like the longest Our Gang episode ever. This means no disrespect to Our Gang, often quite enjoyable on its own level, but not thought of as Oscar material (though an episode did win an Oscar in the late 30s).

Cooper’s uncle, Norman Taurog, who often worked with younger performers throughout his long career, was the director and won the Oscar over such competitors as Josef von Sternberg! As for Cooper, the whole thing bored him and he fell asleep on the shoulder of actress Marie Dressler, who had to gently ease him off to go and collect her own award that evening.

6. An unbreakable record (1931-32)

During the golden age of Hollywood, the studios were well enough organized to be able to direct employees to vote en mass for certain films and individuals. MGM, the biggest of them all in the 30s, was the king of using this practice.

There is no better example of this than the winner of the best picture of 1931-32. Grand Hotel was a huge hit in its day and is still remembered for the commercial formula it inaugurated. Up until then studios would usually only feature one big star in a film on the theory that the public would pay the same price for one star as ten.

What was being missed is that the star power could greatly increase the box office since each star might bring its own public. MGM genius Irving Thalberg finally hit on the idea and thought that the play Grand Hotel, adapted from German author Vicki Baum’s bestselling novel, would be a perfect proving ground, having several roles of equal status woven into its plot.

The eventual stars were Greta Garbo, brothers John and Lionel Barrymore, Wallace Beery, and a vibrant young Joan Crawford, all under the smooth direction of the distinguished and socially popular Edmund Goulding and all the top technical people at MGM worked on it. The film was a huge smash and when the front office at MGM sent out the memos concerning who and what they wanted the studio employees to help push, Grand Hotel was prominently mentioned for Best Picture.

Well, it got the nomination…and nothing else. Now at the time there were usually ten pictures nominated per year (a custom resumed in a modified way in recent years) and it wasn’t that unusual to have nominees in that category garner no other notice but those films were thought of as just being along for the ride. Therefore it was a shocker when Grand Hotel won, despite not having (apparently) anything worth noting in any other category. (Beery won for another film that year but that’s the next story on the list.) This was rather typical of MGM.

The only other film to win Best Picture and nothing else was their own The Broadway Melody in 1928 (though it had other noms). One amusing incident happened in 1936. One of the films MGM pushed to a nomination was the fine comedy Libeled Lady.

One of the stars was William Powell, who was having a great year appearing in not only that film but the eventual winner in that category, The Great Ziegfeld, and copping a nom of his own for one of his most enduring films, the classic comedy My Man Godfrey. That film is still one of the few to be nominated in all four acting categories, and for its direction and script….but no Best Picture nom, unlike Libeled Lady, which was nominated for nothing but that award.

7. The horse shoe Oscar (1931-32)

On the books there have been two acting ties in Oscar history. One was for Best Actress of 1968 with the winners being Barbra Streisand for her film debut in Funny Girl and Katherine Hepburn winning number three for The Lion in Winter. The other was for the Best Actor of 1931-32 but closer examination shows that, in fact, only the 1968 contest was really a tie.

Wallace Beery, a big bearlike actor who has been given a second career wind by the coming of sound, was having a great year between acting in Grand Hotel (actually giving one of the better performances in the film) and his own personal hit, the sports themed male weepie The Champ (which paired him for the first time with Jackie Cooper, his partner in several more hit films).

Though he wasn’t Mr. Popularity with co-workers, MGM boss Louis B Mayer personally liked him and was determined to get him an Oscar for the later film.

Rather oddly, there were only three acting nominees in each of the then existing two acting categories. Beery was up against stage star Alfred Lunt in another MGM film, the sophisticated comedy The Guardsman (which he and wife/partner Lynn Fontanne rather haughtily agreed to make and then fled back to Broadway thereafter) and a surprising third nominee from Paramount, Frederic March for the first talkie version of Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic horror tale Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Horror films were having a famous vogue at the time but, as with most genre films, the Academy didn’t want to know. Had March been any less famous, respected and popular in the film community, or under the direction of anyone less renowned than Rouben Mamoulian, the nomination would have been unthinkable.

Even more unthinkable was the fact that March’s name was in the winner’s envelope come Oscar night, at least to Mayer. Not believing his boy lost, Mayer stormed the Academy accounting office on Oscar night (and, at the time, now sealed information such as the voting results were public). He discovered that March had won by the slimest of margins…one vote. He raised cane and demanded that Beery be given an award also.

Being Louis B. Mayer, he got his way and the ceremony was interrupted to announce there were now two best actors. The irony to modern eyes is that the forced upon performance looks to be the best of the three. March’s simian Mr. Hyde is amusing (Jekyll is rather colorless) but the Oscar would have better gone to make-up man Perc Westmore. Maybe there was some justice, after all.