Primer is an independent movie produced by first-time director Shane Carruth on that most micro of micro-budgets, $7000. After winning the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance in 2004 it recouped a modest 200x return on investment at the box office. But the temporally-displaced fun was only beginning. Primer’s DVD release coincided with the early days of YouTube, and as high-level film discourse was suddenly democratized, few recent films merited sustained discussion more than this impossibly-complex piece of time travel kino.

Primer sometimes gets a bum rap as nothing more than a cinematic Sudoko puzzle. When Rian Johnson faced questions regarding the logic of Looper, he responded, “It’s not a film like Primer (…that deals in the complexities of time travel,) for instance, where the big part of the enjoyment is kind of working out all the intricacies of it. For Looper, I very much wanted it to be a more character-based movie that is more about how these characters dealt with the situation time travel has brought about. So the biggest challenge was figuring out how to not spend the whole movie explaining the rules and figure out how to put it out there in a way that made sense on some intuitive level for the audience; then get past it and deal with the real meat of the story.”

Even though Johnson and Carruth are friends, and Carruth was brought in as an advisor on Looper, Johnson sounds like he’s making a binary proposition: “Either a film can deal with the intricate complexity of time travel, or it can be about the human emotion involved in time travel.”

Perhaps only with the context of Carruth’s second feature, Upstream Color, did audiences realize that Primer, a dialog-heavy two-hander, was itself a character-driven work. Mixed up with the film’s massive jigsaw pieces are important questions around the ethics and emotions surrounding not just time travel, but also scientific innovation. According to Carruth, it’s these questions that give the film its title:

“I saw these guys as scientifically accomplished but ethically, morons. They never had any reasons before to have ethical questions. So when they’re hit with this device they’re blindsided by it. The first thing they do is make money with it. They’re not talking about the ethics of altering your former self. So to me, they’re kids, they’re like prep school kids basically. To call it a primer or a lesson was the easy way to go. And then there’s also this power they have in using the device is something almost worse than death. To put someone else in the position where they’re not sure they’re in control of anything. They’re not in the front of the line anymore and they’re living in someone’s past, to be secondary in that world. The thing that is most important is to feel like you’re at the front of the line, to be prime or primer. I definitely never wanted to say that in the film, but that’s where it comes from.”

All that being said, it is the film’s intricacy that’s made it such a cult phenomenon. So let’s dust off our thinking caps and look at some of the reasons Primer is the most cerebral time travel movie of all time.

1. Director Shane Carruth was a math major who developed flight simulators before making this passion project

In the annals of first-time filmmakers who’ve foregone the day job to pursue the cinematic dream, Shane Carruth’s journey is distinguished at every stage by a fierce intelligence. One of the foremost anxieties facing any newcomer to shooting on film is, “Just what is this going to look like?” It stands to reason that such concerns could be readily deduced away by a guy whose previous workplace deliverables involved teaching pilots how to keep airplanes in the sky.

As he told Indiewire, “Cinematography was incredibly foreign to me, so I read as much as I could about it. Once I figured out that it was just photography with a set shutter speed, I got some slide film and I just went about storyboarding the script and taking snapshots. I took a ton of time doing it just to make sure I knew exactly what I was doing. By the end of it I knew what the film was going to look like — my exposure and the composition and everything.”

He has said that “every inch of film we shot is used in that movie,” meaning he made the classic rookie mistake of essentially editing the film in the can. And yet as a result of his rigorous storyboarding, viewers would be hard-pressed to find a continuity error or glitch in the film’s cohesion. In addition to editing, casting, location scouting, writing, and acting in the film, Carruth also wrote the music. The score is never obtrusive, yet establishes a needling sense of the uncanny.

These renaissance man characteristics can be seen throughout Carruth’s career. His great lost work A Topiary called for expensive CGI effects, yet he hoped to make the film for under $15 million.

While many might shelve the effects, or sell out their vision to get a $100 million budget from the tentpole-industrial complex, Carruth set about teaching himself to develop his own CGI. The results are impressive. A Topiary never got made, but Carruth’s effects work can be seen briefly on a computer screen in Upstream Color.

2. Unlike other time travel films, it actually deals intelligently with issues of causality, free will, and predestination

Time travel films tend to be linear, and rather simplistic in nature. Think Back to the Future or Timecop; i.e., go back in time, change the past, return to your present, and now the present is different. But it’s been 120 years since H.G. Wells wrote The Time Machine.

The Higgs Boson was discovered. The Many Worlds interpretation has gained traction in even the most conservative circles. Current time travel hypotheses put forth by the likes of Michio Kaku involve time travel to a parallel worldline rather than a past identical to our own. Time travel enthusiasts are ready for a fresh take on the genre.

While Primer does not involve parallel worldlines, it does tackle many of the issues around predestination, causality and free will that plagued the traditional time travel narrative. The grandfather paradox is handled by putting short-term limits on the scope of the protagonist’s time travel options, in that they can’t go any further back in time than when the machine was initially turned on.

And while no less than five new Abes and six new Aarons are generated throughout seven different timelines, each new Abe or Aaron disappears into the past, while the previously-extant Abe and Aaron (or sometimes Aaron but not Abe, or Abe but not Aaron) take measures to avoid them.

This brings up tricky problems like, “If an alternate version of yourself possesses an alternate version of your cell phone, and someone calls it, which cell phone will ring first?” And when conflict between the Abes and Aarons does manifest, Carruth’s elegant handling of these interactions is at the root of the film’s brilliance.

3. Carruth refused to dumb down the scientific language

Parobalas, Feynman diagrams, and lines of dialog like, “This isn’t frame dragging or wormhole matching. It’s basic mechanics and heat,” work on two levels. The scientifically illiterate can be left out of the ‘causal’ loop, so long as they believe that Abe and Aaron know what they’re talking about.

For the eggheads in the crowd, it’s a treat when implausible assaults on credulity and good sense aren’t glossed over by a couple silly sounding words like flux capacitor.

4. Carruth had faith that the audience would return to the film for repeat viewings

Carruth himself said that only about 70% of the film would be accessible on the first viewing. Here Carruth is guilty of what so many great intellects do: crediting the slack-jawed masses with having cognitive ability comparable to his own.

Due to the film’s structure alone, it would be impossible for even the most astute viewer to comprehend everything during the first viewing. And for the average viewer, chances are they will be completely out in left field by the halfway point, and just hanging on for the ride by the three-quarter pole

“So that was the intention,” Carruth has said, “To make sure that the information is in there and that at least thematically I’m telling a solid story. So that if you care enough about it, if you liked it, and you want to take another look at it, by all means, the information is in there. That’s my favorite kind of film.”

5. Major plot points are glossed over in seemingly-irrelevant conversation, rewarding viewers who pay extremely close attention

Rarely has so little been spoken—or God forbid, shown—regarding key plot points. Take the pivotal Mr. Joseph Platts. The first reference to him is made obliquely during cross-talk between four people. Subsequent references seem no more significant and are easy to miss amidst the bombardment of information coming at the viewer.

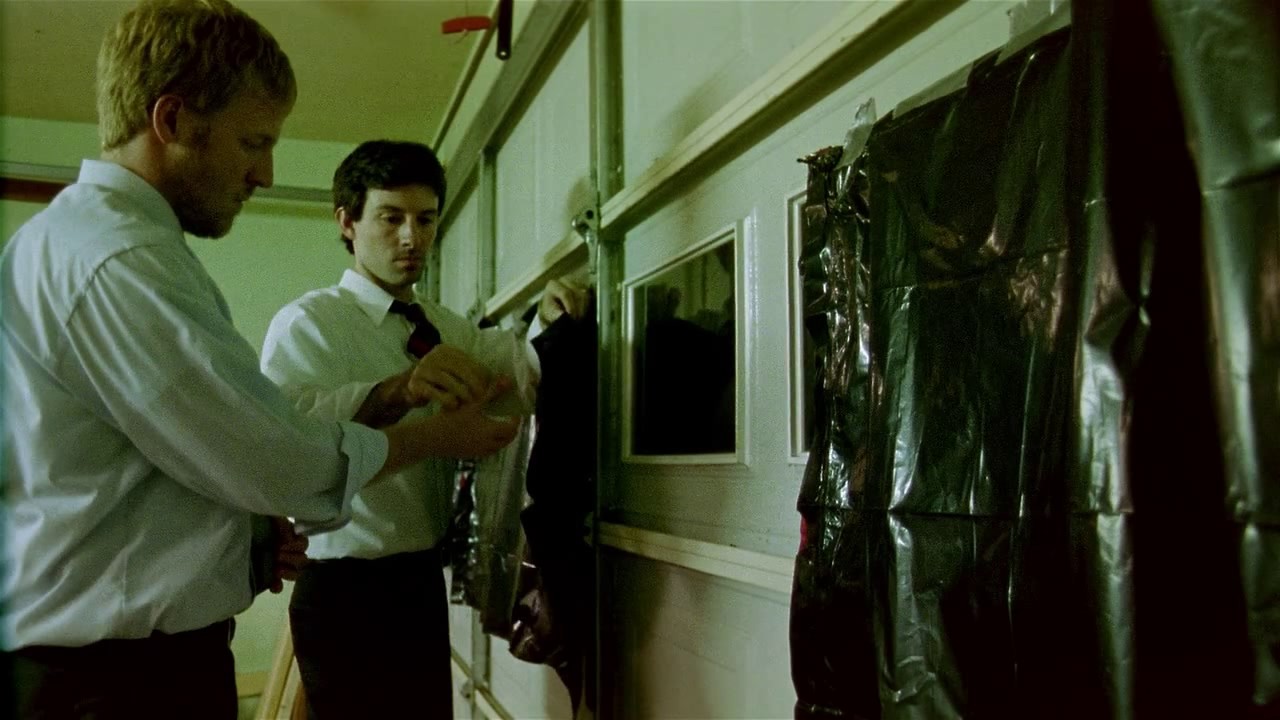

Carruth gleefully breaks that most overstated of writer’s rules: “Show. Don’t tell.” He tells us everything by way of dialog. He shows us almost nothing. And while this may be the result of budgetary limitations, the film somehow emerges all the richer for it.

6. Like other puzzle films, Primer has created its own cottage industry of analysis and speculation

In 2017 we have it easy. After a confounding viewing or two, we can take to the Internet, read any number of detailed breakdowns, and refer to graphs that look like they’re lifted from Fundamentals of Physics before returning for a repeat viewing.

There are weighty podcasts of two- or three-hours duration, lengthy YouTube deconstructions complete with animated graphics, and a chart so dense and complicated that it is referred to by Primer obsessives as “the chart” in tones similar to how religious people might say, “The Bible.”

For the emotionally-stunted and validation-starved: Why not watch it for your third or fourth time with someone who is watching it for the first time. Start Netflix. “Hey, this looks neat.” And when the movie ends, explain every minute detail in a calm but lightly-patronizing tone.

7. Actual science people can’t get enough of it

The culture doesn’t offer much for the empirically-enthused set. Imagine pursuing a doctorate in condensed matter physics or the slightly-sexier accelerator physics, and you can’t even line up in the college cafeteria without overhearing some normie remark, “I’m such a nerd! I love The Big Bang Theory.” Actually, friend, you have been sold a bill of goods that consists largely of trumped-up grade school science.

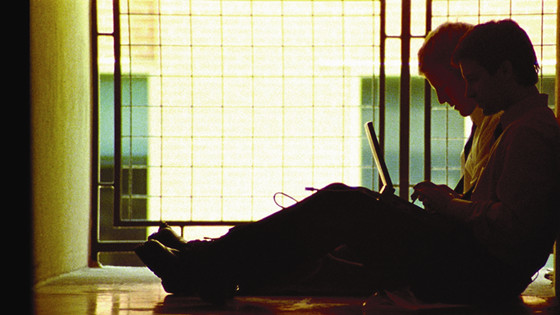

As the YouTube analyses reveal, many first-time viewers of Primer are engineering students hanging out in dorms, writing plot points furiously upon white boards, drinking a lot of coffee before they start the second or third viewing, all while feeling cinematically alive for the first time in ages.

It’s not just students either. At a screening in Queens sponsored by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, Carruth found himself on a panel with several esteemed scientists including “the guy who invented the laser scanner.” Ever humble, Carruth said of the event, “I don’t know if I’ve talked to anybody about what’s happening on a quantum mechanical level, or whether it’s plausible, or any of that. It seems like the scientific community is okay with it. I haven’t been chewed out yet.”

Author Bio: Mike Sauve has written about film for The National Post, Variety and Exclaim! Magazine. His novel “The Wraith of Skrellman” is narrated by a precocious, teenaged “upstart Jodorowsky scholar.” His novel “The Apocalypse of Lloyd” involves an apocalypse that is a Stanley Kubrick production featuring Dennis Hopper, strangely enough. His most recent book “Who Authored the John Titor Legend?” investigates the story of a self-proclaimed time traveller. He has discussed the subject of time travel on Coast to Coast AM, Fade to Black with Jimmy Church and a number of other radio programs and podcasts. Visit his website at www.mikesauve.com or reach him on Twitter @MPSauve.