There is no Academy Award, or any other type of cinematic award outside some of the more fanciful film festivals, given for a certain type of style. This is too bad, for if this were ever to take place, the first in line in terms of deserving it would be director Michael Mann.

Chicago born and British educated, Mann seems to have absorbed the best of both American and European film/dramatic culture in his work. He is a genre specialist and one whose sharp and knowing eye, married to a keen sense of the theatrical essence of his pieces, has made his contributions quite vibrant to both the various genres and to film culture as a whole.

Though several of Mann’s projects have been deemed quite memorable, the consensus in recent years is that 1995’s crime drama/character studies “Heat” may well be his high point.

Though well enough received by critics and audiences at the time (and better than that by the discerning few), not very many gave much thought to the film’s lasting potential, much less that it looks more and more like a masterpiece of what is known as “neo-noir”. How and why did this film get from point A to point B in such a relatively short space of time? The following list will attempt to give some answers on that subject.

1. More about Michael

There are some filmmakers who can conjure magic just be attaching their name to projects. One of these is Michael Mann. He was, as pointed out, educated on two continents. However, his real cinematic education began in the younger, smaller sibling of movies – television, where he was drawn to crime shows. It can be argued that he was one who helped guide the medium in which he still works, to the much more highly regarded artistic place it occupies today.

TV history shows that some of the best work in the medium during Mann’s developing years was done in the crime genre. Yes, he worked initially as writer and director in such standard fare as “Starsky and Hutch”, “Police Woman” (his first directing credit) and “Vega$”, but also on the excellent, forgotten anthology series “Police Story” and the superb made-for-TV movie “The Jericho Mile” (1979), earning Emmys for his script and star Peter Strauss’ performance.

This success set him up for the big screen and he started with his fine script for unjustly overlooked Dustin Hoffman-starring, Ulu Grosbard-directed “Straight Time” in 1978 (now on its way to being a cult New Hollywood classic) and his own feature directorial debut, 1981’s “Thief”, an ultra-stylish caper/character study which bore the locus of things to come.

Shortly after “Thief” came out, Mann’s name became quite well known as the producer and guiding force (though not creator as many did and do believe) of “Miami Vice” (1984-1990), a big hit 80’s fashion show masquerading as a crime/cop show (the memorable first season was a crime/cop show with style but, as Mann’s movie career began to divert his attention, clothes, dwellings, cars and the like started to dominate).

He also produced two seasons of “Crime Story” (1986-1988), a fine series that now looks like a harbinger of the more limited, finite, and sophisticated series which are coming to define TV’s current platinum age as well as a prelude to “Heat”.

In the middle of all of this TV activity, Mann made his first real dent in the movie-going world’s consciousness with the release of 1986’s “Manhunter”, the first adaptation of one of the novels of writer Thomas Harris, which features the character of a certain insane but brilliant psychiatrist/psychopath with most peculiar dietary habits. Yes, this was the film debut of Hannibal Lecter (here played quite well by British actor Brian Cox), albeit as a supporting character

. Although the film loses some strength by straying away from author Harris’ carefully constructed plot midway, the first half, weighed by style and content, may be the best Harris adaptation ever (yes, even more than the Oscar-winning classic from 1991, “The Silence of the Lambs: and decent remake of “Manhunter” from 2002, “Red Dragon”, which was the title of the novel). More than one savvy critic also noted that Mann had cribbed the basic plot for a “Miami Vice” episode shown the season previous to the film’s release.

Following that in 1992 was a version of “The Last of the Mohicans” which gave James Fenimore Cooper’s musty relic of a classic novel far better than it deserved and is still most fondly remembered. Then came “Heat”, which had a long and convoluted gestation, to be covered shortly.

After “Heat” came such notable films like the much-lauded “The Insider” in 1999, “Ali” in 2001, and “Collateral” in 2004 (the same year he produced “The Aviator” to Oscar-nominated effect for the great Martin Scorsese). Some were more acclaimed or popular in their time than Heat, yet this supreme example of Mann’s muscular, masculine, yet oddly ornate and probing style looks better all the time.

2. A good idea is hard to keep down

In the midst of all of this activity, most of it very positive, one big Mann project did not come to pass, at least not in the way Mann envisioned it. His output has often centered on two men on opposite sides of the law, men who have surprisingly much in common, though the thought of ever making a truce is an impossibility.

These men always must fight to the death, though each regrets the inevitability of it all and respects a worthy opponent. This idea came and went a few times on “Miami Vice”, applied in some degree to “Manhunter” and “The Last of the Mohicans”, and was the whole show on the period crime series Crime Story.

However, there was another similar story which was obsessing Mann’s mind in the late 80s. In the 60s, a Chicago policeman pursued a master criminal named McCauley for a very long time and it all ended rather dramatically. Mann thought this was ideal material for the ultimate expression of this idea. His original idea was to turn it into another TV series since that was the medium in which he held the most sway. Thus he shot a pilot, which didn’t sell as a series.

Since Mann’s name did mean something, especially in TV terms, NBC, the network that most closely worked with him, asked him to film scenes providing closure for the plot of the pilot and then aired the results. It was entitled “L.A. Takedown” and aired in 1989. Though there were some critical reservations (Mann’s knack for casting appropriate, if not the most effective, actors, seemed a bit faulty on this occasion), it got some viewers and was rather popular in Europe particularly.

However, Mann would not give up the idea that there was a better expression for this project (around this same time, David Lynch felt the pilot of his failed proposed series “Mulholland Drive” contained some of his best work and, likewise, found an also brilliant way to give it new and better life in 2001). Though he would have to wait a decade to have rights cleared and his own movie cred rise, Mann didn’t give up on this dearly-held idea.

This time, though, everything was going to be right with all the best people on both sides of the camera, as will hopefully be expressed by this list. One of the most important of those elements was courtesy of Mann himself, namely a finely rewritten script which ably fleshes out the characters and ideas. Yes, the film has Mann’s trademark coolness, toughness, and élan in addition to depth of theme and characterization. It all starts with what’s on the page…which quality Heat has on it’s pages.

3. The meeting of two great leads

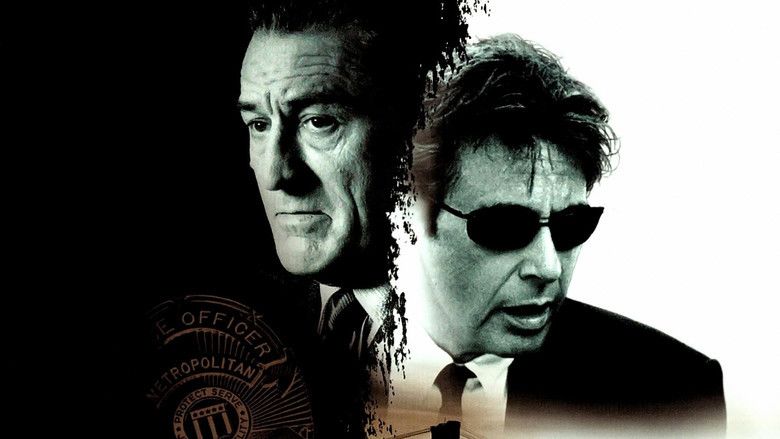

One factor that had seemed to work against the original TV version of the story was that the two lead characters, the poles around which the other characters and events of the plot would whirl, weren’t played by actors of sufficient power and presence. That factor was corrected to a great degree in “Heat”.

Many fine and exciting new actors came along in the New Hollywood era and two of the most acclaimed and intense were Al Pacino and Robert De Niro. Both East Coast-born and no strangers to the legitimate stage, both were the types of non-glamorous performers who would have been relegated to character parts in an earlier Hollywood period, if not left to make their careers on stage and TV.

Both were also devotees of the famed Stanislavski method of acting as presented by New York City’s also famed Actor’s Studio, which stressed actors using personal memories in finding the truths of the characters they portray. In fact, De Niro was infamous from his earliest days as an actor for taking this invective towards verisimilitude to sometimes outrageous lengths.

By common consent, two of the great jewels in the crown of the New Hollywood era were the first two stanzas of Francis Ford Coppola’s exalted Godfather trilogy (1972 and 1974) and those films would play vital parts in the careers of the two men. Both had filmed before those films.

In fact, De Niro made his debut in 1968 and had attracted some real attention in 1973 in both the baseball drama “Bang the Drum Slowly” and, most significantly, “Mean Streets”, his first film with his early patron, the great director Martin Scorsese (sadly, that film wouldn’t be well known until years after the fact).

Pacino, who had a much busier stage career, made a forgettable film in 1969 and then attracted attention in 1971’s “The Panic in Needle Park”, the best by far of the many drug addiction movies of that era, but no more successful at the box office than the others of its kind.

Enter Coppola, casting Pacino (and most of the other cast members) against Paramount’s wishes in “The Godfather”. However, Pacino, like many of the others, was Oscar nominated (rather unfairly in the supporting category) for his performance as crime dynasty heir Michael Corleone and received star-making reviews and starry subsequent roles.

When Coppola reluctantly but brilliantly made a sequel in 1974, Pacino was back to continue Michael’s story, but the writer-director decided to also tell the story of the family’s rise in the crime world with the arrival of Michael’s father, Vito, in New York in the early days of the 20th century.

Though De Niro was, at least partially, of the correct Italian ancestry, he could not speak Italian and, very daringly, all of the flashback sections of the film would be filmed in Italian with subtitles. The actor learned the language, got the role and his first Oscar (Pacino would get another nomination and have to resign himself to bridesmaid status for several more years to come).

By the time of “Heat”, De Niro had added another most deserved Oscar (for 1980’s masterpiece “Raging Bull”) and Pacino had finally won a deserving Oscar, but not really for the right film (for 1992’s heavy-handed “Scent of a Woman”). However, Oscar seemed to work its sometimes reverse magic for both men in that a certain amount of fire had gone out of both careers thereafter.

However, both were still forces to reckon with and this film had the script and roles they needed. Each could have played either part but Mann played on previously established roles, casting Pacino as the morally ambiguous agent of the law (much like his iconic performance in 1973’s “Serpico”), while De Niro played the magnetic outlaw (his rogue repairman/rebel in 1984’s futuristic “Brazil” is as good an example as any).

The two obviously didn’t have any scenes together in “The Godfather: Part II” but would have two excellent scenes in this film. Many had awaited this matchup and their first, bigger, scene is a real keeper as the two characters have coffee together (!), discuss their problematic personal lives and career challenges like old friends, but also renew their quest to fight each other to the bitter end. Only a great set of actors working with a great script and director could have pulled it off. Anyone watching to that point in the film would know that it had all that.