Texan filmmaker Wes Anderson has always been a conundrum Hollywood has never been able to solve. On one hand, his precocious curiosity and deft economy has manifested itself in singularly authoritative, humble and mischievous stylistic inclinations that have gifted us with gems of American independent cinema that have not only some of the best uses of color, costumes, narrative quirkiness and ensemble acting, but have influenced a generation of filmmakers who have adopted his peculiar, comforting style to both excellent and subpar results. On the other hand, you can’t possibly pin him down to one label, however carefully selected that label might be.

Anderson’s distinguishable qualities have evolved over the years due to his remarkable consistency at using the same tools to explore varying ideas that seem to be mounted by the same emotional insights and yet, feel utterly fresh every time. It’s hard not to expect certain things from a Wes Anderson feature and with every film, he seems to both meet and subvert those expectations. You expect his characters to be quirky, the dialogue to be funny and the mellowed color palette to be as washed out as it always is, and yet, with all of that, he seems to underline the narratives on display with a sublime, piercing darkness that grounds the heightened reality of his films.

The characters in a Wes Anderson film don’t interact like they’re in a film. Their language is blunt, direct and while on the surface lacking in subtext, are layered with identifiable realism. Anderson exercises wit like most writers exercise exposition. He never insults the audience’s intelligence, but it’s almost as if he’s a child telling us a story from his little notebook as we all sit around a fire listening to it. His childish naivete combined with an elegantly hipster sensibility empowers his vision with a warm, irresistible flair.

Another discernible trait of his approach is tackling the subjects he chooses with a nearly Kubrickian attention to detail. All his frames seem to contain clues to uncovering an expansive, intricately fabricated vision that pulsates with humor and depth in the smallest of objects and handwritten messages. Through his carefully placed whip-pans and delectable voice-overs, the vastly abundant landscape of his imagination reveals itself to us in multiple viewings.

On the surface, all this makes Anderson seem like a crowd-pleaser. And yet, his films are often quite divisive. Fans of his style are overjoyed at every film of his that holds the prospect of him perfecting it with trademark dexterity. But detractors feel he has been exploiting the same tools with disturbing regularity and essentially making the same the film over and over. It’s hard to argue with said detractors, for they seem to have never been sold on the style anyway.

Ranking Wes Anderson’s feature films is quite the unenviable task. Even if we keep aside the fact that the man has never made a bad film in his career, his films complement each other in tone, atmosphere and overall sincerity to a degree where they’re virtually inseparable and it’s hard to determine which one seems better than the other at a particular point of time. Our relationship with his films seem to change with our own moods and perceptions.

So here goes an attempt to rank his 8 films that can only be, for all intents and purposes, called inconclusive.

8 . Bottle Rocket

Wes Anderson arrived in the world of cinema with a bang. While the box office collections say otherwise, to those who could tap into its electric eccentricity, “Bottle Rocket” announced Wes Anderson’s arrival with much more inventive pomp then he could’ve hoped for. Critics rightfully observed how far Anderson’s potential would take him and were able to see the free-spirited soul of the filmmaker behind all the amateur mistakes Anderson makes in this one.

Revolving around a trio of young men who plan a heist and encounter increasingly absurd obstacles at every turn in the execution, “Bottle Rocket” contains the breezy, light-headedness that sets it apart from the Wes Anderson films that followed. While all his instinctive narrative choices are unmistakable, the film isn’t as contained as the others in his oeuvre, which is its biggest strength and flaw.

“Bottle Rocket” displays Anderson’s unquestionable knack for adventure with an endearing confidence. It is also one of his most outrightly hilarious films, thanks largely to a cast that includes the Wilson Brothers – Owen and Luke, as well as a memorable James Caan. The pacing is as reckless as the protagonists, but if considered as a whole, even the parts come off as ambitious, albeit not fully realized.

7. The Darjeeling Limited

Perhaps the most divisive Wes Anderson film, “The Darjeeling Limited” now feels like a film Anderson could’ve perfected a little more. The attempt is in no way half-hearted, forced or even lacking in the robust, manic energy that can be associated with his other work. But Anderson feels a little out of place here. The setting naturally contributed to the vivid, luscious vision, but Anderson’s discomfort can be easily felt.

Like “The Royal Tenenbaums” before it, “The Darjeeling Limited” is a story of three siblings venturing to escape their realities and exploring uncharted territories to find new identities. The film moves though its meagre plot with deft employment of humor and character and even manages to add requisite depth to the proceedings.

Using the music of legendary Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray, Anderson himself seems to be on a journey here, with no destination in mind. As the film progresses, he seems to be getting closer to getting somewhere and lends sufficient intelligence to the writing to make the journey itself worthwhile. His actors are, per usual, astonishingly natural at portraying touching dynamics of a family that has no one holding it together. Their empathetic work makes the film instantly accessible.

6. The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou

The film the most ardent of Anderson fans have to always defend is actually his most movingly ambitious. It forays into territories that few filmmakers would so early in their careers, and yet manages to infuse a sense of delicious sovereignty and unmitigated joy, even as it almost misses its targets most of the time.

An homage to the great French explorer Jacques-Yves Cousteau, “The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou” follows an oceanographer who cracks a revenge plan to destroy the shark that killed his partner. Insanity ensues in pure Anderson fashion, while we see Zissou’s tumultuous relationship with a young airline pilot named Ned Plimpton, who believes he is Zissou’s son and who subsequently joins his crew.

Bill Murray and Owen Wilson have an irrepressibly charming chemistry. Murray charts Zissou’s arc over the course of the film with some of the most indelible employment of his characteristic deadpan realism. The cherry on the top is the always dependable Cate Blanchett in one of her most underrated performances as a reporter who joins Team Zissou.

Anderson’s visuals form a bittersweet terrain, while his off-kilter set designs effectuate hugely divergent responses from different viewers. In “The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou”, Anderson doesn’t play much to his strengths, and perhaps flies too close to the sun, but it still refuses to conform to any standardized methods of storytelling and demands to be perceived as an autonomous jaguar shark – entirely one of its kind.

5. Rushmore

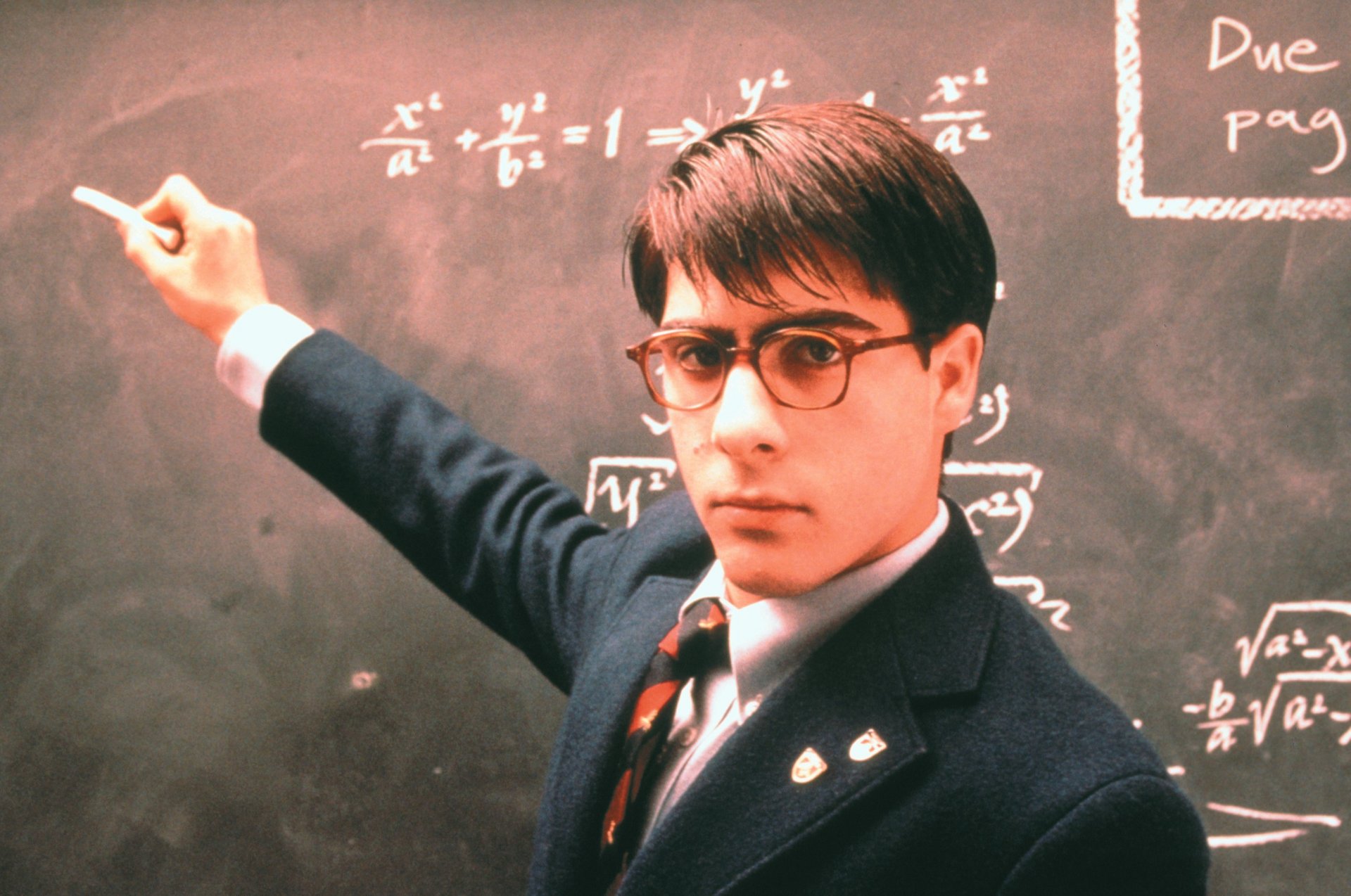

It’s hard to understand how delicate Wes Anderson’s character study of the 15-year-old Max Fischer is on a single viewing of “Rushmore”. Many viewers are put off by the presumably frivolous handling of what are some pretty dark themes. Others find its tonal inconsistencies jarring. But a full comprehension of Mas Fischer’s complex coming-of-age story requires surrendering to the unsentimental, sharp humor and having faith in its ability to lead you to tangible insights.

Max Fischer doesn’t love Rushmore as much as he loves the idea of a version of himself who studies at Rushmore, who excels at everything he ventures into and who for bonus points has a neurosurgeon for a father. Herman Blume is in love with the same Max Fischer and they must stumble upon the devastating conclusion that he doesn’t exist. But life isn’t written in neatly edged chapters, but rather in misappropriated and messy rhythmic convulsions. And so Max has to bid farewell to Rushmore and to the beautiful elementary teacher Rosemary Cross both he and Herman are in love with.

Anderson’s authoritative, visceral touch surrounds Jason Schwartzman’s dizzyingly full-bodied performance with a serene effortlessness. Bill Murray’s subdued vulnerability works wonders at conveying Herman’s inability to see the world for what it is while making his constant attempts to fix everything come off as vivaciously ironic. And Olivia Williams’s quietly wise school teacher might just be the beating heart of the film. “Rushmore” cemented Anderson as an auteur in command of a style that would make him a household name. He wasn’t there yet, but the way he marches to the beat of his own drum here, it was evident he was on his way.