No matter how hard you try, it is virtually impossible to see everything that film industry and small workshops have to offer, whether you’re into mainstream, festival circuit or underground cinema. And if you are a very curious cinephile, then you probably often wish sleep weren’t a vital necessity.

So, whatever your case may be, let this modest selection of the 2010s titles from different corners of the world guide you to the next favorite. From an experimental supernatural drama to a humorous road movie, something will surely strike a chord with you…

1. All My Friends Are Funeral Singers (Tim Rutili, 2010) / USA

The frontman of Chicago-based indie rockers Califone makes his first foray into filmmaking with a quirky fantasy dramedy “All My Friends Are Funeral Singers” which shares the name with his band’s 2009 album. Casting the delightful Angela Bettis in a starring role, Tim Rutili recounts the “folksy” tale of a kind-hearted “psychic advisor”, Zel, who lives a harmonious life with a bunch of ghosts until a mysterious, “heavenly” light shines through the trees of the nearby woods.

Once “Caspers” enter the naughty mode, their “hostess” is precluded from continuing the tarot and palm reading practice, as well as from channeling the spirit of her best friend Camille’s husband Frank and the household starts to fall apart in a maddening cacophony of sounds.

What initially appears to be a slice of (after)life chronicle takes a slightly darker turn in the film’s second half which could be labeled as a melancholy-fueled subversion of a haunted house sub-genre peppered with quirky humor. In addition, there are fourth-wall-breaking mockumentary sequences –almost certainly the work of a specter called Bunuel – which offer (witty) glimpses into the restless souls’ past.

Although most of them are not fully fleshed out characters (after all, they are nothing but the echoes of the humans they used to be), somehow the viewer feels comfortable around them and takes their (sur)reality for granted, just like Zel do. The important part of their charm is a certain je ne sais quoi about the cast of non-professionals, musicians and anonymous theatre thespians, with Califoners as a sight-impaired band whose live-on-set jam sessions bind the narrative non-sequiturs and establish the offbeat “spiritualistic” atmosphere.

Old-wives’ superstitions contained in title cards further help you get into the right mood and the set decorator Keith Kolecki fills the interiors with all the bric-à-brac you’d expect to see in a fortune-teller’s dwelling. The antique magick captured in the eclectic visuals is dispelled in the final shot.

2. Lore (Cate Shortland, 2012) / Germany | Australia | UK

Based on the British writer Rachel Seiffert’s novel “The Dark Room”, “Lore” marks Shortland’s sophomore effort – a fine blend of road movie and postwar drama which gives clear insight into the life of “Hitler’s children” after the fall of the Third Reich.

Accompanied by her younger siblings (sister and three brothers), a titular heroine – the fifteen year old Hannelore Dressler (a magnetic performance by Saskia Rosendahl) – goes on a forced journey across the ravaged land, in order to reach her grandma’s home near Hamburg. When they’re joined by a young Jew, Thomas (Kai Peter-Malina, excellent), Lore is torn between the need for a protector and still smoldering anti-Semitic feelings. Raised in the Nazi spirit, she will have to face the bitter truth that all of her childhood, she has been nourished with lies.

An emotional and perceptive story about growing up too soon, accepting chaotic reality and taking over the heavy burden of responsibility is knowingly told as a bleak, disturbing and fragmented anti-fairy tale holding no supernatural elements. Looking upon Terrence Malick, Shortland relies on loud whispers of the grainy impressionistic imagery and frequently emphasizes the contrast between the misdeeds of men and the beauty of natural surroundings.

Whether she paints the Black Forest shrouded in fog, temporary shelters for the survivors or the ruins with ant-infested corpses lying around, she demonstrates a keen sense of detail, fetishizing the close-ups. Directing the photography is the Australian cinematographer Adam Arkapaw who’s more proficient at hand-handling the camera than, let’s say, Ben Richardson of (epileptic) “Beasts of the Southern Wild” fame. The cacophonous tragedy is complemented by Max Richter’s evocative score and striking sound design.

3. Painted Skin: The Resurrection (Wuershan, 2012) / China

The talented actress/singer Xun Zhou reprises her role as Xiao Wei – a sly fox spirit who is released from her ice-covered prison thanks to a “little bird”, Que’er (the lovely Mi Yang), after fifteen years of captivity. Together with her new friend, Xiao Wei sets off on a quest for human hearts which she has to devour in order to maintain the form of an attractive seductress.

Hoping to find the volunteering “organ donor” who will help her become mortal, she accidentally comes upon a princess with disfigured face, Jing (Zhao Wei, excellent), and offers her a Faustian bargain. Meanwhile, she spellbinds the poor girl’s love interest general Huo Xin (Chen Kun) who blames himself for the accident that has left Jing heavily scarred…

A melodramatic, fairy tale-like story of unrequited love, true beauty and redemption plays out like a parable of what makes us human, focusing on the two heroines’ obsessions. Epic in scope, it involves two subplots – one of Que’er’s relation with a clumsy demon hunter, Pang Lang (Shaofeng Feng) and the other of a barbarian kingdom, Tian Lang, whose queen wants her brother to marry Jing.

As intricate and convoluted as most of Chinese fantasies, “Painted Skin: The Resurrection (Hua Pi 2)” does suffer an imbalanced script, yet Wuershan manages to keep our attention throughout the film and all the way to the cathartic finale, delivering a sequel superior to the original. Unlike his more prominent compatriot colleagues whose historical spectacles take us back to the Far East’s (alternative) past, he builds a fictitious world that follows its own rules.

Free of space/time restraints, his creative team let their imagination run wild and come up with some innovative designs influenced by their own country’s heritage, as well as by Hunnic, Japanese, Turkish, Indian and Tibetan cultures. The sumptuous visuals are supported by CGI and inspired by Yoshitaka Amano’s ethereal artwork, which makes virtually every frame a succulent eye-candy. A bit of grotesque and eroticism serves as an unexpected spice in the melting pot of larger-than-life ideas.

4. Bright Future My Love (Marko Žunić, 2014) / Serbia

The only short film on the list – sardonically titled “Bright Future My Love” – recounts the story of (non-)life in the dystopian future which is, all things considered, not very far from the (Serbian) present.

An unnamed employee is a prisoner of an oppressive society defined by apathy, alienation, consumerist darkness and brainwashing via bizarre TV program. His every day is the same (just like in that Nine Inch Nails song), so his home-to-work route never changes: claustrophobic crib – a decomposing corridor – ramshackle buildings – a concrete railway station – a shabby passenger car – an abandoned industrial complex. But, one chance encounter brings a welcome change with the smell of love…

Marko Žunić utilizes a simple, yet timeless “boy meets girl” concept as a starting point in his exploration of dehumanization in extremely Orwellian conditions. Embracing otherness, not unlike the early works of Cronenberg and Lynch (whose “Eraserhead” he cites as major influence), he skillfully portrays an eccentric, doomed romance, because given circumstances prevent anything “normal” from happening.

Eschewing words turns out to be a wise decision, considering the series of powerful black and white compositions – seemingly inspired by the works of anarcho-cineaste F.J. Ossang and the cyberpunk aesthetics of Shin’ya Tsukamoto – speak crystal clear. Gloomy drones (unnerving buzzing, uncanny hooting, machines clacking) and the sinister hissing of water create the atmosphere of existential anxiety.

As a writer, director, producer, editor, supporting actor and keen-eyed DoP, Žunić has complete control over his work, whereby the non-professional cast’s performances complement his vision. Also commendable is the choice of locations, wonderful in their decrepitude and worthy of the characters status.

“Beautiful Future My Love” is available on the author’s official vimeo channel.

5. Macadam Stories (Samuel Benchetrit, 2015) / France

In a charming ensemble dramedy “Macadam Stories (originally, Asphalte)” or rather, in its central setting which is a decrepit residential building of the French suburbs, three improbable friendships are forged.

Gustave Kervern of (the surreal comedy) “Avida” fame plays a party pooper neighbor, Sterkowitz, who refuses to pay for the elevator repair (because he lives on the first floor and never uses it), only to end up bound to a wheelchair after a treadmill accident. During one of his nocturnal excursions (when nobody goes up or down), he meets Valeria Bruni Tedeschi’s reserved night shift nurse and presumes the identity of a pro-photographer, gradually falling deeper and deeper for the lady.

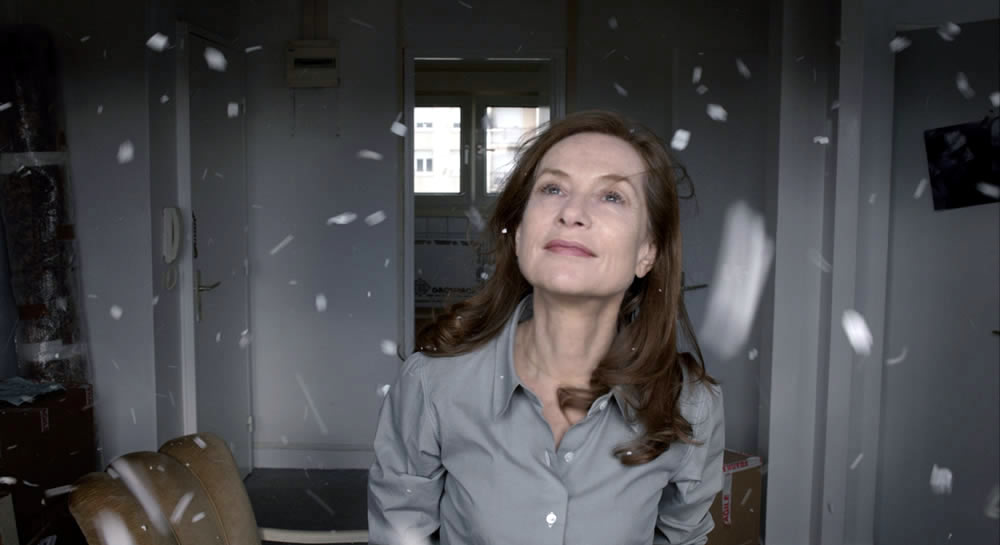

The other story sees the attention-grabbing Isabelle Huppert as a washed-out actress, Jeanne Meyer (an allusion to Jeanne Moreau, perhaps, God rest her soul) who moves next door to an adolescent boy, Charly (the director’s own and very talented son Jules Benchetrit), introducing him to the wonders of old school cinema. In return, he helps her rebuild her confidence and get back in thesp-business.

The third and arguably the most absorbing narrative thread involves Michael Pitt as a NASA astronaut, John McKenzie, who mistakenly lands on the roof of the high-riser and is helped by a hyper-kind Algerian immigrant, Madame Hamida (the outstanding Tassadit Mandi). Unfortunately, she doesn’t speak a word of English, but makes a delicious couscous.

Imbuing the protagonists with remarkable nuances, the entire cast displays an easygoing rapport, as Benchetrit’s screenplay shines with gentle ironies, deadpan poignancy and heartfelt meanings. The grayish palette of Pierre Aïm’s modestly beautiful photography may be cold (as Roy Andersson’s world), but this feature’s humanity lends it many warm hues.