All through Sofia Coppola’s delicately poised filmography, there runs an undercurrent of a desire to dissect female isolation in all its understated, fiery angles. There is gloriousness in her characters living in their own world, staring out windows, looking at a world that would work without any irregularity if it were devoid of them and still attempting to find a place to settle.

The subtleties of her expression of their vulnerability and their tranquility was considered so poignantly unique, her breakthrough film “Lost in Translation” found its place in the pantheon of the greatest cinematic love stories, and earned her the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay.

Not all of Coppola’s films saw the same kind of success, even though each furthered her intense desire to consciously explore the themes of disconnect and abandonment. Even the often misguided “The Bling Ring” had shades of her trademark visual finesse and tender levity, and while not largely offering much to any kind of audience, it provided a template for themes that were not only relevant, but also worth exploring. 2011’s “Somewhere” heartfelt observatory style deserved more than it ever got and her small, but peculiar little royal extravaganza about the iconic French queen “Marie Antoinette” was tragically misunderstood.

What Coppola did with these films is establish a sense of authority one wouldn’t naturally come to expect from a filmmaker of her age. Even though she comes from a family that has had its feet firmly planted on the industry landscape for decades, there are no signs of any influences from the ridiculously influential oeuvre of her father. Her films flutter and dance to their own beat, manufacturing complex details with a benign ease.

After “Marie Antoinette” was met with boos at the Film Festival’s 2006 edition, much was at stake for Coppola, who hadn’t made a feature in nearly 4 years, when she was about to return to Cannes with her reimagination of Don Siegel’s 1970 film “The Beguiled” that starred Clint Eastwood as a wounded Union soldier who is looked after by the women at the Miss Martha Farnsworth Seminary for Young Ladies who have been left alone since the beginning of the Civil War.

The Siegel version was largely an exploitative, melodramatic and, not to reduce its value as a riveting entertainer, ludicrously campy film. Coppola’s take promised to be different and focus on the women’s experiences in that particular strand of time far more than the pulpy story of the 1971 film, based on Thomas P. Cullinan’s novel, ever does. Unsurprisingly, not only did “The Beguiled” delivered on its promises, it proved to be a worthy addition to Coppola’s canon of imaginative, full-bodied portraits of women, bound to one day line the hallways of the great cinematic museum.

So here are 10 reasons why “The Beguiled” is Sofia Coppola’s best film so far.

10. Interpretation of the book and the 1971 original

Coppola’s endeavor closely follows the plot of the book and Siegel’s film, with the stakes being almost the same if taken merely on face value. Yes, a prominent character was dropped from the film, which lead to much controversy regarding whitewashing surrounding the film at the time of its release. But discounting that inarguable misstep, “The Beguiled” is a tangibly faithful adaptation. It retains the atmospheric tension of its source material as well as its discernible potential for atmosphere.

But if looked at from a fresh perspective, this film raises the stakes to a whole new level. The original film, and especially the book, keep the Civil War and its repercussions a constant presence throughout their narrative structure. But Coppola reduces it all to what is essentially background noise. The blood is all to evident but its source is too distant to the main players’ lives for it to be consequential to their isolation. Women have seen many wars before, and they will see many more. Their experience holds more significance here, not the many things that shape it.

Coppola’s film has been labeled as a feminist reimagination of the similar story and she was even unfairly accused of making her agenda paramount and drenching the film of all its raw thrill. What those critics didn’t realize is that she so subtly replaced it with a shaded nuance whose pristine uniqueness is a thing to be cherished, even if it doesn’t reverentially inherit the melodramatic instincts of the original film.

9. The isolation of the characters

There is something that drives the thematic intentions of all of Sofia Coppola’s visual bravura, something that stands toe-to-toe with the dizzyingly sublime landscapes she selects for her characters. Her intent to divulge in every layer of her characters’ isolation from the apparently perfect world surrounding them makes all of her attention to detail and impeccable framing a valid, influential creative choice.

In “The Beguiled”, the protagonists relate their experiences without revealing any well-kept secrets so that only that stranded moment in time when we encounter them in a particular situation distorts our perception of them. As is the case with most of her films, a lot of character work is absent, because it is largely not needed. This suits the visual framework of “The Beguiled”, gradually undraping the emptiness that lies beneath the seemingly fulfilled personas of the women of the school.

Colin Farrell’s soldier is just as unmoored, having left his country only to arrive in a land densely divided. His palpable lust for the women is portrayed with a devilish sense of humanity. Frail and indecorous, all of the characters’ loneliness gradually begins to eat away at them, to the extent that even the most principled of them begin to desire a taste of the flames, and this study of behaviors rises up to the challenge at every single turn.

8. The relationship with history

Coppola’s “Marie Antoinette” was unfairly judged at the time for its lack of historical relevance and its use of pop songs to underline the events that occurred primarily in slow-moving carriages and palatial gardens. Few film enthusiasts who appreciated the film’s delectable vitality understood Coppola’s intentions – she attempted to get into the French queen’s head, to display the most mundane things and sequences riddled with vanity, to understand what Antoinette felt, instead of retelling all that happened to cause those feelings.

With “The Beguiled”, Coppola thankfully hasn’t changed her style of viewing history. It remains an indispensable template for her to base her story on and she never shies away from reflecting on its significance on shaping the way her characters move, the way they so guardedly keep to themselves, or at other times, flamboyantly reject convention and cross lines forced on them by a world they don’t quite fit in.

The characters in “The Beguiled” all think, act and move in a way that makes it clear at all times the period of the story and its consequences. But the Civil War is not at the forefront here because their experiences are so breathtakingly universal, it makes the gap between our time and the time of the film’s setting seem irrelevant. Not much has changed, and not much will. You may wear corsets and gown, and in your head, swoon to the music of punk rock bands. In Coppola’s world, it all makes sense.

7. The production design

When Sofia Coppola is at the helm, the craft of the film tends to lean towards the impeccable. Each fabric of the carpet, each painting, each carriage or even a taxi seem to serve the story with an intelligent, purposeful drive. Whether it be “Marie Antoinette’s” lavish palaces and similar set pieces or “Lost in Translation’s” minimalistic, exotic sets, Coppola has a great eye for production design and she never comprises. She holds the audience’s attention so intensely over the details that some mistake her proficiency in exploiting this detailing for pretentious emptiness.

‘The Beguiled” benefits from this lack of exposition, marking a sly shift in Coppola’s style, while keeping the abilities of her visual storytelling intact. The large house a great majority of the film takes place in creaks and squeaks, adding to the emptiness of the frame and Coppola never allows it to be peppered with excessive details. It remains efficient and translates her deep focus on the women’s experience and their condition into remarkable visual terms, accentuating our sense of their isolation.

The walls here are not decorated, the halls are not adorned with inessential aesthetic. Everything is typically authentic, yet it feels like we are staring at it through a crystal ball – time and people utterly unknown to us – and that makes the film’s believability deviously fascinating.

The curtains do not look washed, but they are clean, reflective of the efficiency with which the school is run. There is a haze surrounding every object and its imprecise serenity feels as if we’re moving through an old, haunted place with a candlestick in hand. Even though different places were used for filming the interiors and the exteriors, the house becomes the most important character of the film – a time portal through which you can look and feel, but not touch. The veil Coppola draws between her film and the audience would ruin the endeavor of a lesser filmmaker, but here it elevates the film’s mysterious persona.

6. The performances

Kirsten Dunst never fails Sofia Coppola – whether it was Coppola’s debut film “The Virgin Suicides”, where her frailty helped in elevating that small, beautiful film to another level, or “Marie Antoinette”, that gave Dunst the opportunity to create a historical character from scratch and one she made entirely her own. She doesn’t fail her in “The Beguiled” either, slowly peeling away such intoxicating layers of sadness as her character’s richly composed history is gradually revealed.

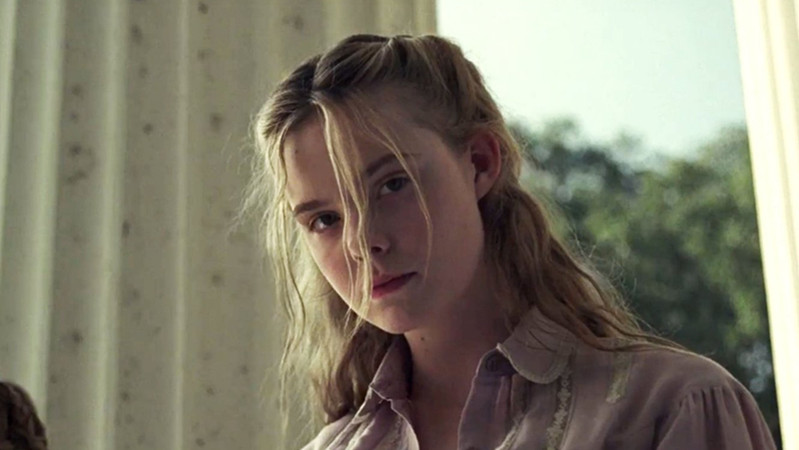

Each performance in “The Beguiled” is so masterfully lived-in that there is no need for any backstories. You are intimately aware of each person’s aura as soon as Coppola places her camera on them. Elle Fanning, one of the most exciting young actors of our generation, skillfully creates as nuanced a portrayal as she did in last year’s “20th Century Women”. She is devious, secretive and childish all at once, without making anything look like a strained effort. The other girls follow her lead and carefully play each beat to thrilling and astonishing perfection, considering most of their ages.

Colin Farrell is consciously vulnerable and functions as the perfect object in Coppola’s study of the male ego. The murkiness of his intentions never goes away. There is honesty in his eyes, but there is something off-kilter in the way he smiles and holds someone’s hands. Farrell plays all the shades as subtly as he played the deadpan comedy of “The Lobster”, but adds to it a riveting self-awareness that lends an aura of ambiguity to his character that is breathtaking to behold.

Kidman is a worthy rival to him, giving a masterful, sensitive performance as a woman who knows and sees everything but says and acts with the utmost care and restraint. Her accent is not consistent, but her poise never stops reflecting how sharp her instincts about the character are. She knows Martha to be a tough woman, but her toughness can always be substantiated with reason. Enveloping her with an air of vulnerability as she intelligently allows her to blur the line between the moral and the immoral. Each performance is human and breathes life into the somewhat staid composition of Coppola’s stunning visuals.