Like all the best artists, many filmmakers have taken it upon themselves to ask big questions with their work, questioning reality, identity and the meaning of life. Such explorations of the human experience are often intense, and can have earth-shattering conclusions.

These are the kinds of movies that may have you curled up in the fetal position by the end, not because of intense emotion or shocking imagery, but because they will make you question everything you thought you knew about yourself.

Put simply, an existential crisis is when an individual questions whether life has any meaning or purpose. It is often associated with psychological trauma or a major life event. Although watching a movie may not be a major life event, it can have a significant impact on the way a person thinks or sees the world at large. After watching these 15 movies, you may never see the world in the same light again. Oh, and you will definitely have an existential crisis.

1. Ikiru

Have you ever wondered how you will be remembered after you die? If so, you certainly aren’t alone. Filmmaker Akira Kurasawa tackles the meaning of life and death in the haunting drama Ikiru (translated as “To Live”). The story centers on Kanji Watanabe (played by a luminous Takashi Shimura) who, after thirty years is an unexciting bureaucratic position, discovers that he has terminal stomach cancer, and decides to do something significant with his final months.

Watanabe first decides to live for pleasure, joining some newfound friends in an all-night romp, but realizes quickly that the things he believed would give him enjoyment are not lasting. Rather than determining that life has no real purpose, Watanabe makes one last effort at meaning. After witnessing a group of mothers continually spurned in their efforts to petition the government to clean a cesspool near their homes, he takes it upon himself to clean the area and build a playground for their children there.

The park is completed just as Watanabe passes away, and at his wake, his involvement in the park’s construction is discussed at length. The sad fact of the matter is that, although he had control over his actions while alive, Watanabe has no control over how they will be interpreted after his death. Many of the men speak patronizingly of Watanabe’s final attempt at meaning, even taking credit for his hard work and sacrifice. Even Watanabe’s son doesn’t speak very highly of his father. It’s a maddening story that turns terrifying when the viewer realizes that s/he will have no impact on his/her personal legacy.

2. The Seventh Seal

Ingmar Bergman’s existential classic deals with one of mankind’s greatest fears is a very unique way. Set in medieval Sweden, The Seventh Seal follows a knight (Max Von Sydow) returning home from the crusades, only to discover that his homeland has been ravaged by the plague.

When the knight encounters death in person, he strikes a deal with death and bets his life on a game of chess. Their game continues periodically as the knight comes face to face with the worst of human nature.

The knight and his squire witness devastating sickness, infidelity, cruelty, and horrifying religious self-harm. The depraved actions of the characters of The Seventh Seal force the viewer to wonder whether there is any goodness inherent in human nature. As the wanderers acquire more travel companions, the knight’s chess game with death takes on a new meaning: he fights against death to keep his newfound friends safe.

In contrast to the greed and depravity around him, the knight attempts one small act of goodness and kindness. In the end, however, he realizes that death is inevitable and his attempts to create good in the world are so short-lived they appear meaningless. The concept that death will nullify our attempts at meaning is certainly a terrifying existential thought.

3. L’Avventura

L’Avventura practically caused a riot when it premiered at Cannes in 1960, causing its director and star to flee the theater. Audiences first encountering Antontioni’s revolutionary film had no idea what to make of it, and many viewers coming across it today still won’t.

Claudia (the beautiful Monica Vitti in her breakout role) joins her friend Anna and Anna’s boyfriend Sandro on a boating adventure to some islands near Sicily. Upon arrival, Anna quarrels with Sandro and promptly disappears.

Although the rest of the boating party spend a good deal of time looking for her, Anna is never seen again, and the narrative maddeningly moves on without her. In Anna’s absence, Claudia and Sandro begin a passionate affair, after only knowing each other for a few days. Unfortunately, their romance is not without distraction, and Sandro ends up deeply hurting Claudia.

Many have accused L’Avventura as being a film in which nothing happens. This isn’t far from the truth, but perhaps this is because real life is rarely exciting. L’Avventura is all about distraction; Claudia and Sandro have a mystery right in front of them that any Hitchcock character would obsess over, but they become immediately distracted.

In the end, even their romance is not enough to hold Sandro’s attention, and director Michael Antonioni seems to be suggesting that in a world full of distraction, meaningful human connection is simply not possible, even though it is something we desperately long for. The idea that all of our attempts at meaningful relationships will be unsuccessful is enough to send anyone into an existential crisis.

4. Persona

Yes, another Ingmar Bergman film. Honestly, every one of Bergman’s movies is an existential crisis waiting to happen, but Persona is easily one of the most pervasive. When actress Elisabet Vogler (Liv Ullmann) goes inexplicably mute, she goes for some respite in a seaside cottage with nurse Alma (Bibi Andersson). The two become strangely intimate, as Alma reveals her deepest secrets, and in the end, Alma practically goes mad questioning her own identity.

Psychiatrist Carl Jung used the word ‘persona’ to suggest the outward identity an individual projects in order to guard themselves. Bergman’s Persona is certainly interested in the differences between image and identity. One telling monologue even suggests that “every inflection and every gesture [is] a lie.”

Worse than the concept that we cannot be true to our identity is the concept that identity may be an illusion. Although Alma attempts to maintain her own individuality, when Elisabet’s husband comes to visit, he mistakes Alma for his wife.

Eventually the women’s identities literally merge into one in one shocking scene. The horrifying implication here is that all people are essentially the same, and that the idea of the individual is a myth. Of course, Persona is a film open to several interpretations, but each comes with its existential questions.

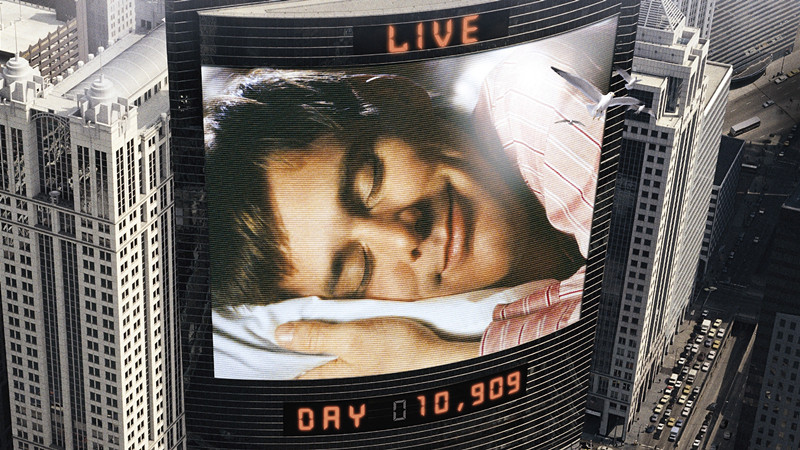

5. A Clockwork Orange

In Stanley Kubrick’s brilliant interpretation of the Anthony Burgess novel of the same name, juvenile delinquent, Alex DeLarge becomes a victim of the system. Alex (played with gleeful energy by Malcom McDowell) is far from innocent himself—his chief interests, according to the film’s poster, include rape, ultra-violence, and Beethoven. When Alex is arrested for murder, however, he undergoes an experimental procedure to cure his bad behavior.

What follows is essentially sessions of classical conditioning training in which Alex’s penchant for violence is undermined by crippling nausea. When his rehabilitation is demonstrated to a group of officials, the prison chaplain complains that Alex’ free will has been taken from him, but the Minister thinks this is a small price to pay to reduce violence and crime.

A Clockwork Orange brings up several questions about freedom and identity. Even the characters who claim to care about Alex, really only use him as a pawn in their agenda. Alex’s freedom of choice is taken from him in more ways than one, and we are left wondering if our own identity is so malleable that our choices can be made for us. If those in positions of influence wanted to condition us to act a certain way, could they? And even more menacing, have we been conditioned without realizing it?

6. Blade Runner

A sci-fi staple, Blade Runner’s stunning cinematography and distinct mood are impressive, but what really stays with the viewer are the existential questions. Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) is a ‘blade runner,’ a hitman hired to track down and kill rogue humanoid robots called replicants. His latest assignment has Rick (and the viewer) questioning the meaning of humanity and empathy.

Early in the film, Deckard pays a visit to Tyrell Corporation, a replicant manufacturer, and discovers that Tyrell’s beautiful niece is actually a replicant. This revelation comes too late, as Deckard has already begun to develop feelings for her, and when Deckard learns to have sympathy for one replicant, it becomes harder for him to see all replicants as ‘others.’

As Deckard hunts down the rogue replicants, we realize that we care about them as well, cringing when they are gunned down, and hoping secretly that they will find a way to coexist with humans. At the film’s climax, one replicant gives a monologue about existence and memory that will give the viewer chills, and blurs the line between man and machine. Blade Runner asks what it really means to be human. We like to think of ourselves as superior beings, but if a human-like personality can be manufactured, is our identity and existence really significant?

7. Slacker

Almost all of Richard Linkalter’s films deal with existential issues in some way or another. The Before Trilogy deals with the potential for meaningful human connection, and Boyhood studies the passage of linear time, but Slacker deals explicitly with the philosophy of the working man in a unique way. Following denizens of Austin, from hippies, to hipsters, to misfits, to anarchists, Slacker eschews narrative for a series of conversations seemingly eavesdropped upon.

The entire cast is a group of generation X bohemians trying to find themselves and figure life out. This sounds like a great idea in theory, but Linklater’s characters are exactly what the title implies: a parade of slackers without real goals or ambition.

Although the film romanticizes the ‘slacker’ movement, Linklater is aware of the potential hazards of the bohemianism on display. The characters consistently challenge common sense and even each other in their attempts to discover truth. The film makes assertions impossible to back up such as: “The passion for destruction is also a creative passion” and that “Time doesn’t exist.”

Slacker is a buffet of existentialism. If taken literally in its entirety, it presents such a hodge-podge of ideologies and philosophies that the end result is a Gordian Knot of thought, overwhelming enough to induce an existential crisis. Fortunately, Linklater doesn’t take his message too seriously, assigning everyone names like Disgruntled Grad Student and T-Shirt Terrorist that transform them from characters into caricatures. Even with the tongue-in-cheek humor, there is an earnestness to Slacker that will definitely have you contemplating your existence.