Frogs falling out of the black night sky. An oil well owned by a man possessed by greed blowing up. A drug-infused investigative endeavour. Two men fighting in a garden, rolling around on the grass – in love or repulsion? Dissecting the emotion that drives the characters or the storyteller in a Paul Thomas Anderson film is a futile task. The crystalized imagery is so inherently pristine, that it makes the reason for why a particular emotion exists or why many particular emotions exist, utterly unnecessary. The only thing of consequence is that an emotion does exist, and there is palpability, there is urgency to it.

Anderson’s perception is so singularly incisive and intelligent, that more often than not, you have no choice but give into the shaded absurdity of some of his most radical ideas. Brimming with consciously crafted detail, his films rage and rile like the placid ocean in “The Master” and whisper and contemplate without saying almost anything like Phil Pharma in “Magnolia”.

In a time when most filmmakers seem content with attempting to tell the same stories as were being told decades ago, wrapping them in the neat packages of modern convention, Anderson’s stylistic traits seem nearly old-fashioned, in that they still seem to consider cinema as an art form that can be moulded, reshaped and pushed to new extremes. He began his career with the frenzy of an artist afforded opportunities few harbouring the dream of filmmaking ever come across.

There is an urgency to express anything and everything that ever came into his head and a certain restlessness that wouldn’t go away unless all of those ideas had been expressed. This impatience benefited the films he made in those initial years, breathless with the layered exploration of their characters’ experiences, accompanied by an intoxicating poetry that elevated those ideas to a level of mystifying, epic realism.

In his recent films though, he has begun to exercise much more discipline, both in the craft and the design, but in the structure and the patience with which he employs his narratives to captivate us. This became evident with 2007’s “There Will Be Blood”, considered widely to be his masterpiece – a sprawling, gritty, unsentimental, yet richly emotional epic on greed and ambition.

The films that followed still retained the vivid sense of experimentation similar to the high of his earlier films, but exhibited a more ruthless, sharp visual and acoustic energy, making them much more effective experiences. That’s not to say the earlier films lacked an eye for the filmmaking tools he has become so adept at exploiting, but in his more recent work, he has begun to understand more of experiential qualities of cinema, taking risks that are in turns reckless and carefully considered.

So here are 10 reasons why Paul Thomas Anderson, with his meagre filmography, has become the greatest filmmaker of our generation.

10. Experimentation

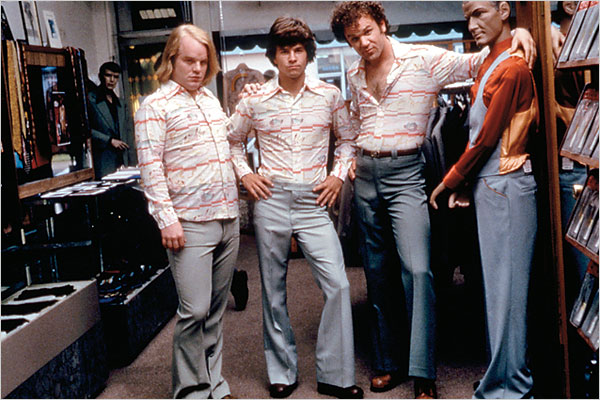

Let’s consider the filmography of the subject of this article. He began with “Hard Eight”, a noir film based on his short film “Cigarettes and Coffee”. The film doesn’t demonstrate Anderson’s strengths the way the others do, but still shows a willingness to take unlikely tonal leaps most would assume to be jarring. He followed it with his humane examination of the adult film industry, where he deploys such meticulous detailing to his crafting of each character and their believable loneliness that for a second feature “Boogie Nights” is a gigantic step forward.

In “Magnolia”, Tom Cruise hisses and expositions about the superiority of men and how they, with will and intelligence, can conquer the weaker sex, while his father dies an unhappy, bitter death. A lot of highly divergent things happen to a lot of other people, all connected to each other somehow, and all telling the same story: when we are beyond repair, we can only be saved.

He lurched forward with the oddly romantic comedy “Punch-Drunk Love”, by the end of which the only thing that makes any sense is the relationship of the two protagonists, the lemony tinge of sadness making the film a small-scale miracle in its own right.

“There Will Be Blood” doesn’t need any further adoration and “The Master” is a love story of two men – one who cannot be controlled and one who desires more than anything to control the former – masquerading as a telling of how cults came into prominence after World War II left everyone feeling unmoored. “Inherent Vice”, his most recent adventure, is based on the highly complex Thomas Pynchon novel, inheriting the humour and the darkness of its source material entirely to create a full-bodied, if somewhat incoherent imagery of the world of Pynchon.

All this can only be evidence to how diverse and bold Anderson’s creative choices are, not only in terms of the delectably risky subject matters, but also in terms of the narrative scope of his films. “Magnolia” and “Punch-Drunk Love” for instance, are the most intimate examination of vulnerability, but their universality expand their access to landscapes much wider than their prickly absurdity might suggest. “There Will Be Blood’ and “The Master”, on the other hand, seem to be painted on a much larger thematic canvas, but focus as intently on the tiniest of strokes as they do on the big ones.

In the hands of a less inventive filmmaker, the blueish white hue that makes much of the vinegar-like “Punch-Drunk Love” resonate would have been a catastrophic misfire, but Anderson plays with it like a precious child with his new-found toy in that he takes the risk of never leaving it alone, and it pays off in multitudinous ways.

9. Subtly Intense Focus on the Craft

Like the dangerously subversive and fanatically attentive Stanley Kubrick, Paul Thomas Anderson tells more than half of his story through the detailing of the lighting, the production design and the costumes. There are secrets to be unravelled within the knotty textures of an Anderson setting and he lays it all almost deceptively bare for the audience to discover.

This is not to say the craft, which also includes the deftly implemented sound design and the staggeringly moody scores of his films, is only to relate the filmmaker’s thematic intentions, which if communicated otherwise, would lose all their enigmatic qualities that make them so utterly transfixing in the first place. It also induces a nearly indescribable other-worldly sense of pleasure at being witness to such indomitable command of the cinematic tools.

In films like “Boogie Nights” and “Magnolia”, the craft is almost singularly purposed for character development. Each aesthetic choice reflects a deep understanding of extending the character’s experience to a degree where it touches the muddied realm of wisdom.

There is wisdom in the warmth radiated by the dying man’s house and in the impossibly expressive eyes of his compassionate nurse, while standing sharply in contrast is the dying man’s son lecturing men on how to win over women in his glossy attire. There’s also wisdom in the wailing of a woman who can only tell her most secret predilections to a pharmacy store worker, the store’s densely placid colouring contrasting brilliantly with the woman’s deep red fur coat and her bright red hair.

Anderson has begun to venture more frequently into historical narratives, giving his diligently manufactured craft the opportunity to adorn his bold storylines with textured, inventively populated frames. With “There Will Be Blood”, “Inherent Vice”, “The Master” and now the upcoming “Phantom Thread”, which promises nothing short of being the most meticulously crafted of all of his films, his reflection of our ever-fascinating perception of history has only gotten more breath-taking to inhabit. But at the end of the day, the sheer omnipresence of the blue-white colour palette of “Punch Drunk-Love” should suffice in informing anyone of how Anderson interweaves sensual cinematic pleasure with deviously knit observations on the human condition.

8. Radicalism

In the past few years, cinema has become a medium where either radicalism can exist or realism. When Kubrick, Bresson, and even Lynch were in their prime, both could exist without causing the film to be a complete disaster. Cinema was still being explored as a medium of expression and the likes of Jodorowsky and Buñuel were expanding the perception of the audiences who had never seen anything like their work.

It was almost an inaccessible combination of reality and unsheltered radicals that transcended the medium and became something beyond the cinematic language audiences assumed they were well versed in. The blood is real, but the reason it flows is beyond our reach. We not only feel the pain, we are also captivated by the mystery of its muddied cause.

But since the form took the established shape it finds itself in today, real stories are rarely radical and the radical ones seem to be either too far off our condition to be of consequence or depressingly self-indulgent. Paul Thomas Anderson is that invaluable contributor to the cinematic evolution whose oeuvre is neither too radical nor too real.

It’s a double whammy of tangibly heartfelt realisation of our deepest emotions cooked with exactly the right amount of fluidly singular absurdity. His films do not purport to carry a higher meaning or neatly shaped messages. They begin as a reflection of life at its basest, gradually building up to a crescendo of pure, cinematic, off-kilter mastery.

Anderson can manipulate your senses with something as small as an unusually long pause or as huge as a song all the major characters of his film break into out of the blue; throwing you off the scent and still somehow holding your attention in his palm. There is grittiness and pulsating emotion to his narratives, but his visual styling ensures that a sweeping limitlessness is constantly felt by us.

There is a vastness to his intimacy and a raw untarnished reality to his odd affinity with the epic. So, is Paul Thomas Anderson a radical? One would be inclined to say yes, and there is a part of Anderson’s fluttering, breathless, at once stoic and impatient style that wants to be called a faithless radical. But that does not mean we must be swift to do so.

7. Symmetry of the Camera

Like the other filmmaker who shares his last name, Anderson is known for a painstakingly diligent composition of the frames of his films. The other Anderson knows how to exploit the impossibly symmetrical frames to assign a mysteriously lived-in discipline to his hipster sensibilities.

This one uses it in such a rebelliously breathy manner that blink and you will miss the economic employment of this symmetry that works more as a filmmaking tool than a storytelling one. It makes a quantifiable difference to our experience, even in places where the story would suffice to appease us and a lesser filmmaker would be willing to limit himself to that. But it would be half a film when compared to the one Anderson would make.

This symmetry is not just restricted to what populates the frame, but also includes the way those objects do so. They are colored in ways so honest to the way the story and the dialogue serve the characters and the thematic intentions of the filmmaker.

As Anderson is evolving as a filmmaker, his frames, in their askew simplicity, are pulsating with a greater authority and vibrancy – a combination so rare it makes the work of filmmakers who either disappear into their ivory towers once their presence has been established on a global stage or those who continue to take risks that have never paid them off, seem embarrassingly inferior.

Like another one of his great contemporaries Todd Haynes, Anderson has, with time, conceded to becoming a part of the industry that profits off of their art but has had his feet firmly planted on the outside. He looks at his characters as tiny specs of sand disappearing into the desert or a man of incessant greed overpowering another one of cloth, but has constantly, despite all the odds stacked against him, captured them in the most generous lights and the most forgiving colors, making them more human than any sentimentalist ever could.

6. Cool Irony

Irony is that unattainable cinematic high most filmmakers don’t come in proximity of, let alone comprehend the dynamics of. Literature, admittedly, offers more accessible opportunities for ironical narratives and themes but great filmmakers have, in the past, led us into the darkest nightmares only to subtly make us realize that all they are attempting to do, even in post-apocalyptic avenues and historical fiction, is hold a mirror out to us and leave us as ill at ease as possible. Few are able to pull this off without the heavy-handedness of forced, unnatural comical detours and even fewer with the kind of covert airiness that adds a subtle believability to even the most acidic infusion of irony that Anderson so frequently, so consistently does.

Take for instance, the ending of “Boogie Nights”. In what is only his second outing as a feature film director, Anderson takes all of his characters out of their misery at being confronted with reality, only to bring them back to their world of make believe because he knows their denial is their only saviour.

While on the surface, he has given them a happier ending than we assumed they would get, his treatment of their surficial joys is delectably ironical, best exemplified by Mark Wahlberg’s final monologue in front of his green room mirror. He can see himself in the mirror, and not shy away from his reflection. Can we say the same about ourselves, Anderson delicately asks, ending his film, like the best of movies, with a question that is not only unanswered, but is largely, unanswerable.

The animalistic tendencies of Freddie Quell, the enigmatic protagonist of “The Master” is only human when he gives up all control of his senses, to break and contort his body in ways so abhorrent that you can’t look away. When he quietly reflects on a past love, or peacefully submits to his deplorable condition, he seems to belong from another world.

Peggy Dodd, another player in this endlessly fascinating landscape, passionately convinces her husband after he has humiliated himself in a high society gathering of how inconsequential the eccentric scepticism of the big city is. But in Amy Adams’s incandescent performance, her devotion comes off more as ambition, the purpose of which is only to fuel her husband’s ego, and if you were comforted by it, how are you any better?