To love cinema is to be a padawan in the art of gold mining for obscure films around the world, learning about different cultures through their rich artistic expressions.

There’s a bit of Indiana Jones in every movie buff, or there should be, since intellectual laziness never does well. So to help with this goal, I have selected titles from various parts of the globe that deserve greater recognition. Don’t waste time, start today!

1. Seven Beauties (1975)

Italian director Lina Wertmüller (who started as assistant director to Fellini) caught the attention of the world with this film, even breaking the sexist chain of Hollywood and being the first woman to compete for an Oscar for Best Director. The greatest merit of production is not in this fleeting award event of American self-celebration, so immersed in politics, but in the strength of its script and the incredible courage it shows in each frame.

The greatest challenge was to use comedy as a tool to tell the story of Pasqualino Frafuso (Giancarlo Giannini in an impeccable performance), a man who lives in appearance, false morals and cowardice. He disrespects any sense of ethics, but reacts violently (and clumsily) whenever his seven sisters are exposed to some humiliating situation.

The humor is born when we realize that the “Seven Beauties” are incredibly devoid of any charm or grace, accentuating the feeling that we are facing an allegorical work. Our clumsy hero ends up getting involved in a crime while trying to maintain the honor of his family, which ends up leading him to a court and a downward spiral of events, where he will be stripped of all ego and self-love, against background the Nazi rise in World War II.

Giannini works his characterization with subtle references to Chaplin, evidenced by his looks and his walk. The classic vagabond, even surviving a precarious existence, maintained his refined “pose,” as did Giannini’s Pasqualino, who conceals a corruptible and fearful heart wrapped in a secure, bon vivant and authoritative pose. This position is already clear in the early stages of the work, when he witnesses the murder of Jews by the Nazis and does not seem to feel remorse for not trying to avoid that slaughter.

The critique of conformism (already included in an efficient way in the music that starts the film) becomes more and more direct, while the protagonist finds himself having to make increasingly degrading decisions, such as flirting with a rather attractive German at a concentration camp, in an attempt to escape the hell of war. As one of the characters states in the film, when order is driven by chaos, only a disorderly man can be saved.

The greatest triumph of the movie is to make us cheer for a non-heroic protagonist. A man who survives from his cowardice. Someone who shapes his character through the obstacles that confront him. The wonderful final scene accurately expresses the traumatic consequences of this lifestyle.

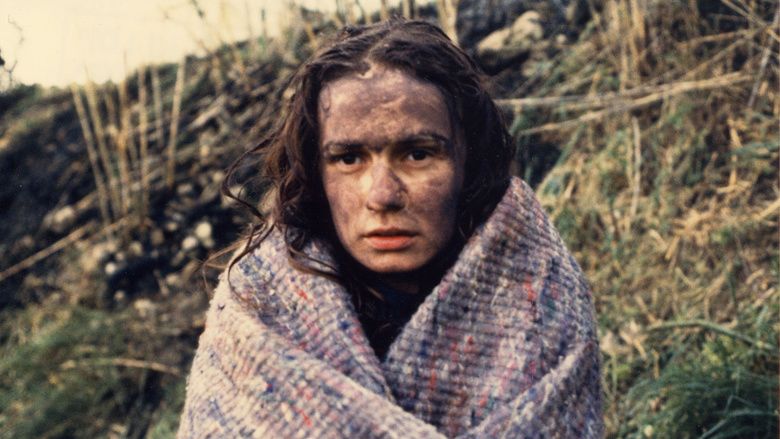

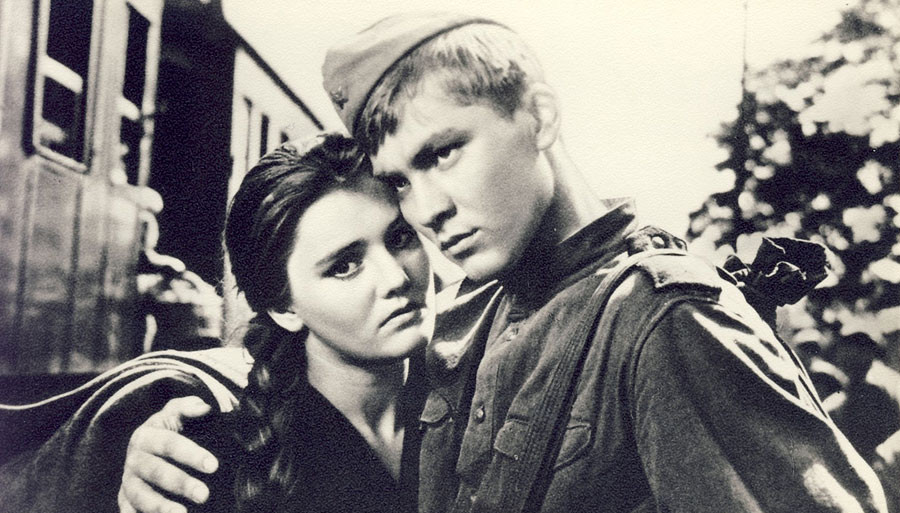

2. Ballad of a Soldier (1959)

One of the arguments I listen to most from moviegoers when I suggest movies that are not part of the Hollywood circuit is, “There you come with those Ukrainian art movies.” As I firmly believe that the initial step for anyone interested in breaking the seventh art is to risk looking for diamonds encrusted in the deepest rock formations, I usually point out “Ballad of a Soldier.”

Seen today, it presents an agile and fully efficient narrative structure, thrillingly telling the odyssey of a 19-year-old soldier, an immature boy thrown in the midst of the cruelty of war. After clumsily performing a heroic feat in battle, he receives an honorable notification from his superior. Distraught from not having been able to say goodbye to his mother in his humble village, having followed his road leaving behind an unfinished repair on the roof of his house, the young man asks his superior that in the place of the notification, he can have at least one day next to his mother, promising to return next.

The goodness of the young Alyosha (Vladimir Ivashov), who ends up various times risking to deviate from his desired goal, seeking to be useful to compatriot strangers (like the soldier who lost a leg and intends to let his wife believe that he died).

A quick and beautiful scene occurs soon after the young man knows the reality of those who await the return of the soldiers, indulging in frivolous passions as a way of escape. He meets the weakened soldier’s father, choosing to lie to reassure him about the high status of his son, while the father chooses to lie to the young man about his son’s wife, asking him to return and tell him how much she loves him and awaits her return. Both know that they are deceiving themselves, but respect prevents them from showing it.

Dramatic moments like this keep its vigor, as well as the efficiency of the comic relief, represented by the figure of the young and bountiful officer on the train, who clandestinely accommodates the young soldier and a beautiful girl (Zhanna Prokhorenko), his first love.

3. Not One Less (1999)

The saga of a stubborn teacher and a child who would not be a statistic. An impressive effort by sensitive director Zhang Yimou to portray the most beautiful side of human nature.

With a cast of amateurs who use their own names (and occupy functions similar to their characters), “Not One Less” tells of a 13-year-old girl (Wei Minzhi) who lives in a poor Chinese village, far from civilization. When the teacher of the humble local primary school needs to be absent for a month, the mayor summons the girl to be the substitute teacher. The modest payment will be given if she is able to avoid giving up the children. Families are poor and there is no hope in the eyes of students who express their anguish by acts of rebellion.

Zhang begins the work making us believe that the obstinacy of the girl is guided only by the payment, but throughout the plot he moves us to show the devotion of the old teacher, who, with a limited amount of chalk and no money to replace it, even uses the powder left on his fingers to complete his teachings on the blackboard. This love, which is only explained by the genuine vocation, ends up contaminating the young woman, who embarks on an arduous journey (external and internal, of maturity) to rescue the most strenuous student of the class who had fled to the big city to find work.

The discussion that the work fosters, between the lack of demotivating perspective and the progressive stimulation of the girl in fighting for that single student, establishes an inspiring and realistic parable. In the course of her journey (which begins at school, when she and the children carry bricks, intending to pay for the bus trip), she ends up spending a lot more money than she would receive at the end of her mission.

On the other hand, we are presented the figure of a secretary of the city, who is unable to show compassion when denying help to the girl. Zhang introduces us to an adult woman who denies a simple gesture (which would take her only a few minutes), while the young woman exudes maturity by keeping her aim to the point, sleeping in the street. The documentary naturalism of filming adds value to it, causing us to identify with the situations and hope that the protagonist can find the boy and take him back to school.

Like any 13-year-old child (not so different from the ones she must teach) in the same situation, she starts focusing only on not letting any of them escape. Before she even boldly ventured into town, her actions already demonstrate that something has changed in her (matured) and, more importantly, in the students. Her stubborn devotion proved to the needy children that they are not statistics. The exciting finale makes it clear that where formerly dominated hopelessness and chaos existed, the light of self-esteem is now shining. The internal change was much greater than the external one, coming from the young woman’s journey.

4. Aniki Bóbó (1942)

Portuguese director Manoel de Oliveira has already received much criticism for his esteem for the long takes, present in almost all of his works. His detractors argue that cinema is the art of movement, not a collage of still photos. With good humor, the filmmaker says that his long takes are not photos, in these fixed planes there can be a lot of movement. His keen cinematographic gaze assured him the position of a symbol of the Portuguese cinema. Among all the films of his career, my favorite is “Aniki Bóbó,” his first feature-length fiction and one that’s unfairly very little known (even in his country).

Another brilliant Portuguese writer named Fernando Pessoa once said, “no children’s book should be written for children”. The same can be said about cinema. Rarely do studios make films aimed at the children’s audience with intelligence and refinement, believing that just putting an incompetent director on the front line with a lot of color and a minimum of creative ideas will win the attention of children and the money of adults. It is not always that beautiful works such as “The Boys of Paul Street” and “Stand by Me” appears in cinemas.

With “Aniki Bóbó,” de Oliveira created a poetic tale that can be seen as a cinematographic equivalent of the literary work “The Little Prince” from Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, aside from being great as an instrument for a first appreciation of his work, for being simple and very objective. My advice to those who like this: do not forget to watch also “The Divine Comedy” (1991) and the interesting “A Caixa” (1994), to fall in love with the director’s style.

The story of the film is based on the short story “The Millionaire Boys” by João Rodrigues de Freitas, and tells the adventures of a group of Portuguese children, and their first loves and frustrations. It is interesting to note a certain similarity between the lyrical gaze on de Oliveira’s childhood and François Truffaut in his majestic “The 400 Blows,” released 17 years later. I sincerely believe that de Oliveira’s work influenced that of Truffaut, being a forerunner even of the neorealist movement.

Among my many favorite scenes is one in the beginning, when the grumpy schoolteacher does not notice that a cat is walking through the window, causing the whole crowd to shake. Trying to put order in the room, he screams without success, but when he bangs his table for silence, the cat is scared and runs away, causing the children to express sadness with a sigh.

Another comical scene that still provokes laughter is the one in which the owner of a store (lived by the fantastic Nascimento Fernandes, who began his career acting in Brazil), after being irritated with a child who had called him a giraffe, slaps his assistant. Frightened, the young man questions the reason, in which the man replies, “I can not beat the customers!” A simple scene, but with a perfect rhythm that becomes funnier than on paper.

Another one that does not last more than a few seconds, but which enchants me, is when the trio of child protagonists are in front of a shop window of the same store (aptly named like “Shop of the Temptations”) and admire a doll. There is a poetry in these few seconds.

5. Bab’Aziz – The Prince That Contemplated His Soul (2005)

This is the best film in the desert trilogy directed by Nacer Khemir, with scenes that linger in one’s memory for a long time, like the dance of the young Ishtar and her grandfather in the desert, and the way the narrative mirrors “1001 Nights” with the grandfather (like Scheherazade) telling the fantastic story of the prince in parts to entertain the girl, who is getting more and more fascinated. The script (written by the director in partnership with Tonino Guerra, who also wrote “Amarcord” and “Blow Up”) is based on the dignity and devotion of the noble Baba Aziz, who knows that death lies in wait and tries to teach his knowledge to his spiritual granddaughter, who accompanies him on the journey.

As in the first movie, we have a character who represents the contemporary world. A young man in a denim jacket and cap meets Baba Aziz (Parviz Shahinkhou) and his young granddaughter Ishtar (Maryam Hamid) as they walk on the desert sands looking for the site of the great gathering of dervishes (nomadic Muslim monks), which occurs only once every 30 years.

The young man is present initially by the sound of his singing, which leads us to the first moment of rare beauty in the work. Asking the elder about which way to go, the sage responds, “You should just walk.” Worried about getting lost in the undulating vastness, he listens to the girl: “He who has faith never loses.” Baba then hands over a beautiful symbology: “Each one uses his most precious gift to find his way, yours is the voice, then sing my son, that the way will show itself to you.” He continues singing until he disappears into the horizon.

The essential message that Khemir wants to pass us through is lyrically represented in the final speech of the dying old man: “If they told a baby trapped in the darkness of his mother’s womb, there was an illuminated world out there with high mountain peaks, endless oceans, undulating plains, beautiful flowering gardens, creeks, a sky composed of a myriad of stars and a scorching sun, the baby without knowing these wonders, would not believe such things could exist as we do when we face death. This is the reason for fear.”

In Khemir’s view, the search for “God” (“the truth to reach God is in the very interior of man” – Agostinho) is an incessant yearning for self-knowledge and appreciation of the human being, in search of a crystalline feeling and a detachment material. The “Desert Trilogy” is rich in symbolism, beautiful to admire, and with a philosophical richness rarely seen in cinema.