Greek cinema has not always been what you would call a flourishing business. Unsupported in terms of state funding and obstructed by tribulations and prohibitions of the country’s recent political history and the economic crisis that made things financially even more challenging especially for new directors, Greek cinema has not been very popular among audiences worldwide during the past century. As a matter of fact, it has been, unfortunately, underestimated even by the Greek audience.

However, there has been a list of directors who managed to make their presence felt both in the indigenous and in the global cinematic spotlight over the years, including Theo Angelopoulos, Nikos Koundouros, Costa Gavras, Nikos Nikolaidis, Michael Cacoyannis, Tonia Marketaki, Pantelis Voulgaris, Nikos Grammatikos, Stavros Tornes and others.

Despite the adverse conditions, while we progress from the dawn of the 21st century onward, Greek cinema is becoming more and more productive and appealing to audiences worldwide. Some modern Greek directors are represented in the following list, with Yannis Economides, Panos H. Koutras, Nikos Grammatikos, Alexander Voulgaris, Constantine Giannarisand Argyris Papadimitropoulos having the greatest effect among them.

Its freshly acquired universal reputation has been enhanced by the appearance of a rather new cinematic style, the Greek Weird Wave, established by Yorgos Lanthimos’ “Dogtooth” in 2009, which has inspired and now extended to other directors like Athina Rachel Tsangari, Alexandros Avranas, Babis Makridis and others.

This list is an effort to gather the best Greek films of the past 18 years, attempting for the titles to be as representative as possible of various directors and genres.

20. Wednesday 04:45 (Alexis Alexiou, 2015)

Stelios is a jazz club owner, ambitious and unresistant, on the verge of losing everything. He has repeatedly been neglecting his family over his work, bringing his marriage to an upcoming end. His greatest problem, though, is that he has 32 hours to come up with the money he owes to a Romanian loan shark gangster.

“Wednesday 04:45” is a drama film by Alexis Alexiou with the ambition to marry Greek pop culture with American neo-noir and Asian horror, and although it doesn’t absolutely live up to its creator’s expectations, it constitutes a decent effort, taking a rare (for Greek cinema) risk and therefore earning its place on the list. The film is divided into titled chapters, with a combination of dark, rainy shots and bright neon lighting to create a nightmarish noir atmosphere.

On a second level, it comments on the current situation in Greece with a lot of people ending up in debt and their dreams collapsing on the arrival of the economic crisis. Stelios Mainas as Stelios offers the film its greatest credit, however, with his fine, sentimental performance.

19. One Day in August (Constantine Giannaris, 2001)

It’s the 15th of August and, like most Athenians do, three families living in the same building leave the city for vacation, each toward different destinations. But this vacation is going to be eventful for everyone. In a parallel narrative, while the tenants are absent, we witness a young boy breaking into their houses who lives their lives for a while and reveals their secrets.

Three families, three images of the Greek middle class prior to the economic crisis, nine people, nine stories, nine dreams on hold, nine disappointments, nine desires. The hope for a change, for a miracle, common in all of them. Symbolically transcendental and realistic at the same time, the film attempts to render the balance between tragedy and magic defining life itself.

“One Day in August is a road movie […], where the tenants of a three-floor building at the center of Athens speak to us about love. About the absence of love. Where love collapses. […] And in the suffocating summer heat, their dreams and desires come true.” – Constantine Giannaris

18. Amerika Square (Yannis Sakaridis, 2016)

Billy and Nakos are childhood friends who have lived all their lives in Amerika Square at the center of Athens. Billy is a tattoo artist who falls in love with Tereza, an immigrant singer involved with the underworld. Nakos, on the other hand, cannot accept the fact that his neighborhood’s square has changed dramatically over the past years, turning into a shelter for immigrants and mainly Syrian refugees. And Tarek is a Syrian refugee who desperately searches for a way to flee to Germany with his daughter.

Based on Yannis Tsirbas’ novel “Victoria Doesn’t Exist,” “Amerika Square” is a film about racism. Other than a fair representation of the current situation in Athens, the film is more than that. Yannis Sakaridis uses Greece and the refugee crisis to set the background that allows him to speak about racism in general.

Understanding and kind to his characters, even those who “do wrong” but without justifying them, he sets the scene and lets his point get across sort of by itself. And that is the simple but not always easily acknowledged fact that racism is not just something “bad” that appears out of nowhere, but a learnt behavior that emerges from certain circumstances and is reinforced by certain circumstances. Circumstances the “victimisers” are also victims of.

17. Milk (Giorgos Siougas, 2011)

Having emigrated from Tbilisi years ago, Rina and her two sons, Antonis and Lefteris, are trying to survive with dignity and ensure normalcy in their lives in Greece. Antonis intensely wants to forget about his past and origins in an attempt to be integrated.

Unlike his brother, Lefteris (portrayed beautifully by Prometheus Aleifer), who also struggles with mental illness seems to be attached in his memories, desperately trying to find acceptance and love. Rina, while trying to make ends meet, has the difficult role of endeavouring to balance the opposite forces of her sons and rebuild a home for them in the new country.

Based on the stage play of the same name by Vassilis Katsikonouris, “Milk” is a touching film exploring the concept of home in the sense of a safe space, and the relationship between homeland and the sense of belonging, as well as the important need for acceptance. It approaches the process and the difficulty in constructing a home when you are regarded as stranger.

Responsibility one is not willing to take or doesn’t know how to take, mental illness, stigma, liberation, voids that won’t be filled, anger, disappointment, maternal and homeland archetypes, fixation, and memory as a source of distress or comfort are discussed with care and subtlety in Giorgos Siougas’ film.

16. Miss Violence (Alexandros Avranas, 2013)

On the day of her 11th birthday, in a seemingly joyful atmosphere, Angeliki jumps off a balcony. As the police and welfare try to investigate into the reasons that urged the girl to commit suicide, the family’s decorous facade starts to fall apart and a repulsive family truth, rotten at its very core, timidly rises in its place.

Alexandros Avranas made a social drama about, as the title indicates, violence: sexual abuse, domestic violence, psychological violence, about its brutality and its effects. But really he made a horror movie, for the truth it depicts is a horrific one. With a deliberate choice of exaggeration in its theme, counterbalanced by the strictly structured frames and lighting and the steely, disciplined performances, the director manages to create a concise film which extends the discussion from the family to the society and the violence and hypocrisy concerning it.

What lies on the other side of closed doors is often scary and therefore ignored as nonexistent, until we can’t afford to ignore it anymore. “Miss Violence” reminds the viewer that tolerance is a stance and that appearances can be deceptive. But can it really ever not show?

15. Suntan (Argyris Papadimitropoulos, 2016)

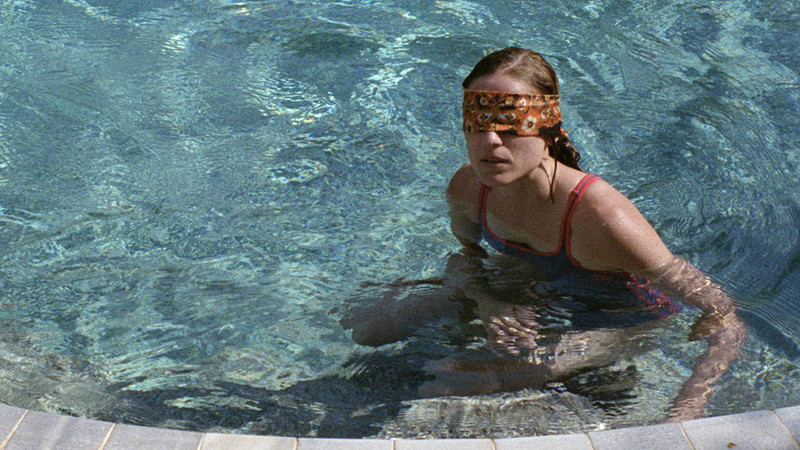

Kostis is a doctor assigned to work in the health clinic of the Greek island of Antiparos. He is not exactly young, not exactly successful, not exactly handsome, not exactly happy, not exactly anything. Anna, on the other hand is a pretty 20-year-old tourist who has come to the island with her friends to party. Kostis falls for Anna’s charm and soon he starts obsessing over her.

As Argyris Papadimitropoulos has stated, the idea for the film came from a division of people between those who have access to pleasure and those who don’t, found in Michel Houellebecq’s novel “Whatever.” Kostis (an outstanding performance as always by Makis Papadimitriou) and Anna represent the two different types of people, the two different worlds, raising questions on how each perceives their reality, is perceived by others and eventually place themselves based on their ability to access pleasure within the context of our modern world.

In a somewhat hedonistic summer background, the director introduces a dialogue on pleasure, lust, middle places, and the decadence ensuing the long gone youth and beauty.