The adage that good artist copy and great artists steal is in practically cliché at this point. Yet if this demonstrates anything it’s that many a great filmmaker is nothing if not the sum of their influences; even if their influences merely told them to be true to their original artistic voice.

Though the early days of film present an alarming lack of diversity, one must be conscious of the era these artists were operating in, and take extra time to salute the few within this list who made it possible for all peoples to be the influential filmmakers for the next generation. Here, chronologically, are the twenty most influential filmmakers in the history of cinema…

1. DW Griffith

Griffith remains something of a black (face) sheep in the history of cinema. Something of a Roman Polanski of his day, many cinéphiles and scholars of film and history struggle to reconcile his innovative contributions to the art form with the discomfortingly racist ideology of his film Birth of a Nation.

Griffith is typically recognized as a pioneering force in the legitimization of filmmaking and transposing it from a novelty attraction to a legitimate form of storytelling. His films introduced viewers and imitators to many a technique that would become permanent fixtures in filmmaking vocabulary. His dynamic camera use and editing techniques challenged the conventions of film temporality in his era.

2. Sergei Eisenstein

The philosophical notions of the camera’s eye and its use in ideology is well documented in the early days of the Soviet Union with such movements as the innovative Kino-Pravda newsreels of Dziga Vertov, but it’s the work of Sergei Eisenstein that stands above the rest.

Widely regarded as the father of the art of montage, Eisenstein recognized that stylistic editing was not only a useful tool in building the rhythm and flow of a film, but that particular montage could have thematic and ideological significance.

Eisenstein is widely credited for being one of the first auteurs to marry cinema to ideology and use the new art form as a channel for propaganda the way filmmakers like Leni Riefenstahl and Carmine Gallone would for future regimes.

3. Fritz Lang

Cinema and spectacle have been intrinsically linked since its genesis, and it wasn’t long before entertainers and wizards like Georges Méliès discovered that the moving picture wasn’t limited to a glorified stand-in to the stage performance, but could be exploited in fantastical ways.

Méliès may have been the first to merge film and fantasy, but it was German expressionists such as Fritz Lang that expanded the boundaries of how a fictional world could be.

Expressionism is the art of externalising the internal. Demented characters and sinister landscapes wear their hearts on their sleeves. Backdrops and set pieces take on surreal, warped proportions, and coloured filters are used to enhance mood.

Lang’s expressionist-era magnum opus is undoubtedly Metropolis; a work groundbreaking in its contributions to set design and science fiction. Any dystopian feature as well as any film to feature humanoid robots all owe a debt to Metropolis, whereas the legacy of expressionists at large can be seen in the brooding colours of Douglas Sirk’s and Dario Argento’s films, as well as Jean-Luc Godard’s Le mépris (in which Lang plays as himself, incidentally); as well as the melancholy aesthetics and design of Tim Burton’s films.

When sound films became the norm, Lang’s world-building prowess evolved to accommodate it. In M., Lang uses off-screen sounds in order to fortify the impression of a vast city that the characters inhabit. Not to mention his use of leitmotifs like “In the Hall of the Mountain King”.

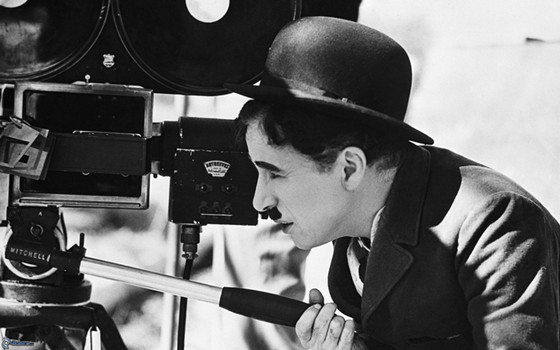

4. Charlie Chaplin

Comedy films of the early days of silent cinema drew inspiration from the American vaudeville tradition, with slapstick and physical comedy being the lingua franca. One such master of onscreen physical comedy was Buster Keaton, who was known for his daring and extravagant stunts.

Yet, however perfectly timed and executed Keaton’s domino-like setups would go, they lacked emotional depth. This is where Charlie Chaplin comes in. While with Keaton, one would marvel at the intricacy and timing with which the dominos fell; Chaplin, on the other hand, would make you feel and sympathize with each falling domino.

After a flourishing reign over silent cinema, Chaplin blazed onward into the sound-era of the 1930s with an ardent desire to keep his onscreen persona, The Tramp, voiceless. As a result, Chaplin became one of the few filmmakers to so defiantly resist “talkie” cinema. This setback mattered not, for Chaplin never struggled to convey sentiment and story through sight alone. Combining laugh-out-loud slapstick with genuine heart and sympathetic storytelling, Charlie Chaplin is recognized as a true innovator of the visual language.

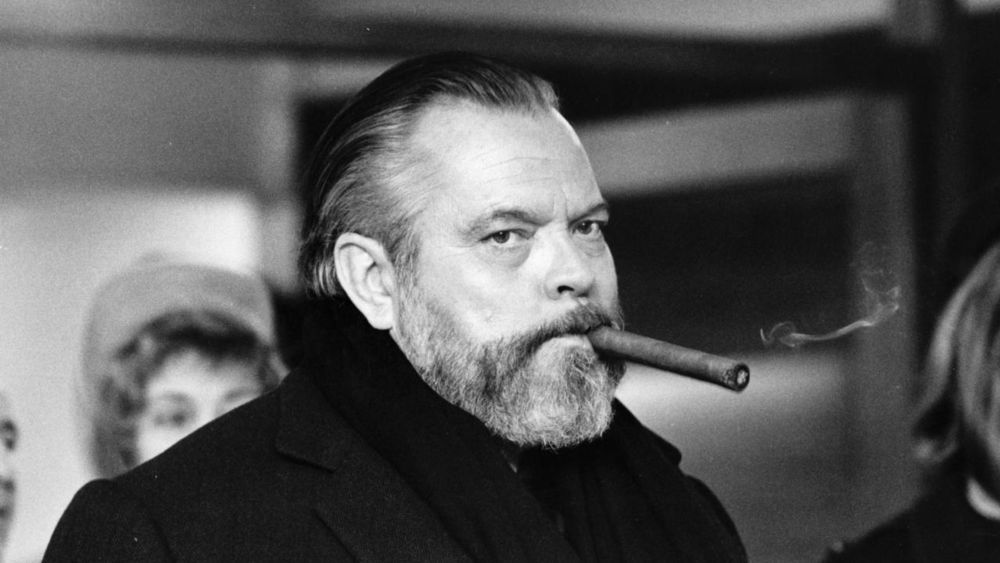

5. Orson Welles

Orson Welles’s technical innovations to film include the long tracking shot and the use of forced perspective to enhance the grandeur of a scene, but most significantly is Welles’s contribution to mise-en-scène. Eisenstein may have conveyed meaning through the juxtaposition of shots, but Welles was able to craft symbolism through the depth of one single shot.

A prime example of this is the scene in Citizen Kane (a film equally groundbreaking in its use of non-linear storyline), where instead of alternating between two simultaneous scenes as pioneered by Griffith, Welles shoots the sit-down between the parents of Charles Foster Kane and banker Walter Parks Thatcher with the living room window in the background; out of which we can see a young Kane playing with his sled while his parents negotiate Thatcher’s raising of their boy. This juxtaposition illustrates what would come to signify his loss of family and innocence in the pursuit of wealth and resource.

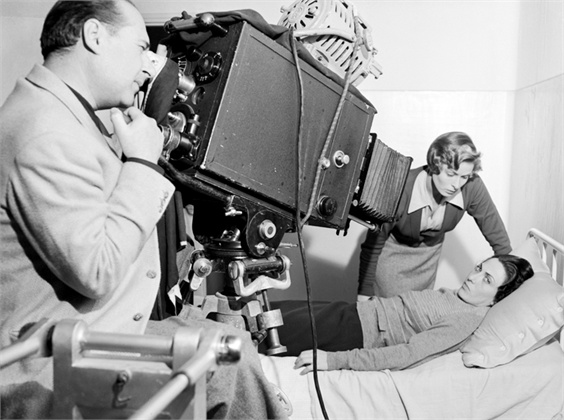

6. Alfred Hitchcock

The title of engineer or technician would be a more apt description of Alfred Hitchcock’s filmmaking duties rather than merely “director”. The British filmmaker was noted for his meticulous attention to detail, and the actors in his films were known to be considered “moving parts” in the visual stories he told.

While horror directors could effectively provoke emotional responses from their audience with the aid of the unseen; shrouding the threat in mystery and ambiguity, Hitchcock’s preferred avenue of suspenseful filmmaking was much more challenging; the threat was fully known to the audience, and it was time during the establishment of this threat and the moment it revealed itself that Hitchcock spent bringing his audience to the edge of their seat.

For example, in Rope, the spectators know there is a dead body in the room; it’s just the matter of when its presence will be uncovered by the other characters. Hitchcock’s masterful command of suspense and dramatic irony would make him a patron saint for thriller directors now and forever more.

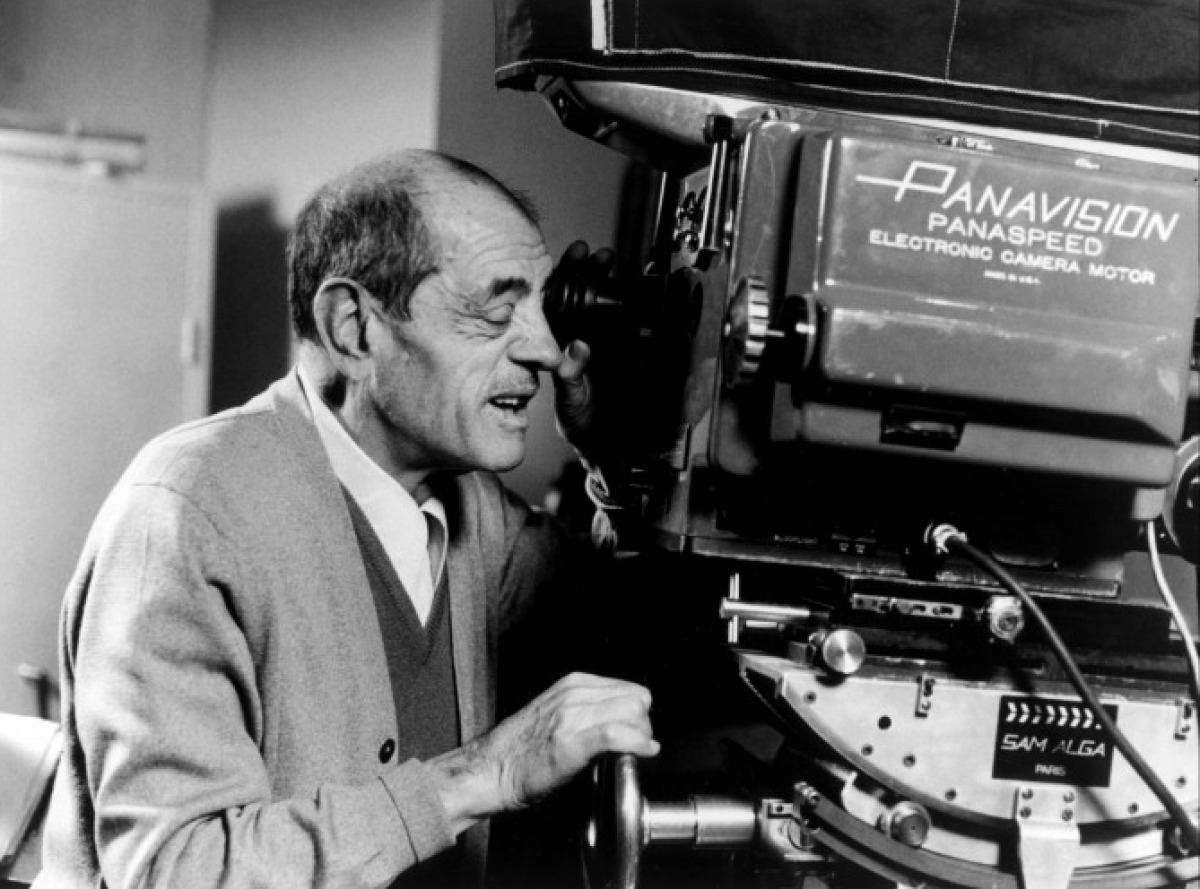

7. Luis Buñuel

While film was still widely viewed in academia as a platform for popular entertainment and a distraction from everyday worry, bold artistic talents such as Spanish surrealist Luis Buñuel would exploit cinema’s potential as a fine art worthy of display in museums.

Perhaps what is most remarkable about Luis Buñuel is his utter disregard for narrative logic. In typical surrealist fashion, Buñuel’s characters often find themselves in impossible dreamlike situations that would go onto influence the works of David Lynch, Jean Cocteau and Alejandro Jodorowsky; as well as Denis Villeneuve’s film, Enemy.

One concrete example of this is the sequence in The Phantom of Liberty, in which a couple searches for their missing daughter—accompanied by their missing daughter, which can be compared in absurdity to the scene in David Lynch’s Lost Highway wherein the protagonist is prompted by a mysterious man in black to call his home phone, with the voice on the other end of the line belonging to the man in black standing directly in front of him.

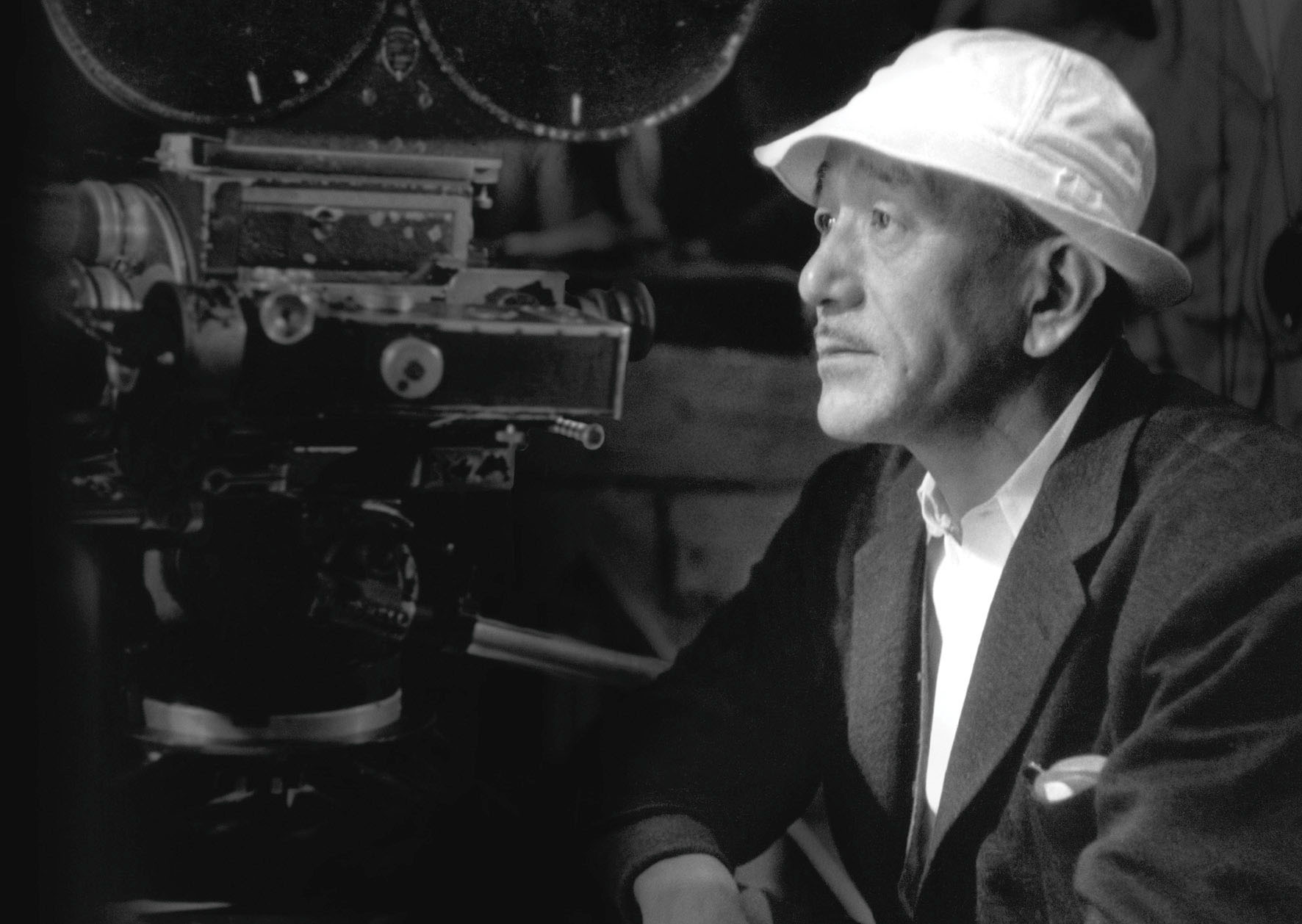

8. Yasujiro Ozu

While many filmmakers embraced the innovations in sound and filmic world-building brought forward by artists like Lang and Welles, Yasujiro Ozu’s work conjures a certain purism reminiscent not only of the silent film period, but of the early years of cinema which more closely resembled a stage play.

Much like classic Lumière short films such as L’Arroseur arrosé, Ozu strives to contain the entirety of his cinematic world with in his shots, with the main action at dead center. To Ozu, there is no( what the Lumière’s referred to as) hors-plan, or off-screen/out of frame. His entire world is condensed into the frame, and the result is typically a masterful example of mise-en-scène.

In terms of content. Ozu was a master in what is called gendaigeki, a genre of Japanese media that deals in contemporary drama about modern Japanese life.

One can see the influence of Ozu’s mise-en-scène most notably in the films of Wes Anderson and Xavier Dolan. The former of which thrive on centering the action and concentrating on what goes on within the shot, without a great deal of depth. Although Dolan’s films are much more three-dimensional that Ozu and Anderson’s films (see the long hallway shots of Lawrence Anyways), his affinity for symmetry to the point of gaudiness can be traced back to Ozu’s work.

9. Roberto Rossellini

While the definition of the term “modern” can be quite divisive, many film scholars agree that cinematic modernism emerged in part due to the Italian neo-realism movement.

After the end of the Second World War and the fall of the fascist regime, it became more difficult for Italian filmmakers to so easily churn out the idyllic escapism that cinema had presented heretofore. Rossellini, along with other neo-realists such as Vittorio De Sica, crafted a more representative vision of Italian life both during and after the war; depicting the toils of the Italian working class against a war-torn backdrop populated by mostly non-professional actors.

After the height of Italian neo-realism in the late 1940s, Rossellini would go on to make modernist dramas such as A Journey to Italy featuring then-wife Ingrid Bergman; the atmospheric, freeform narratives of which would greatly influence other Italian filmmakers such as Michelangelo Antonioni in his portrayals of a disaffected privileged class.

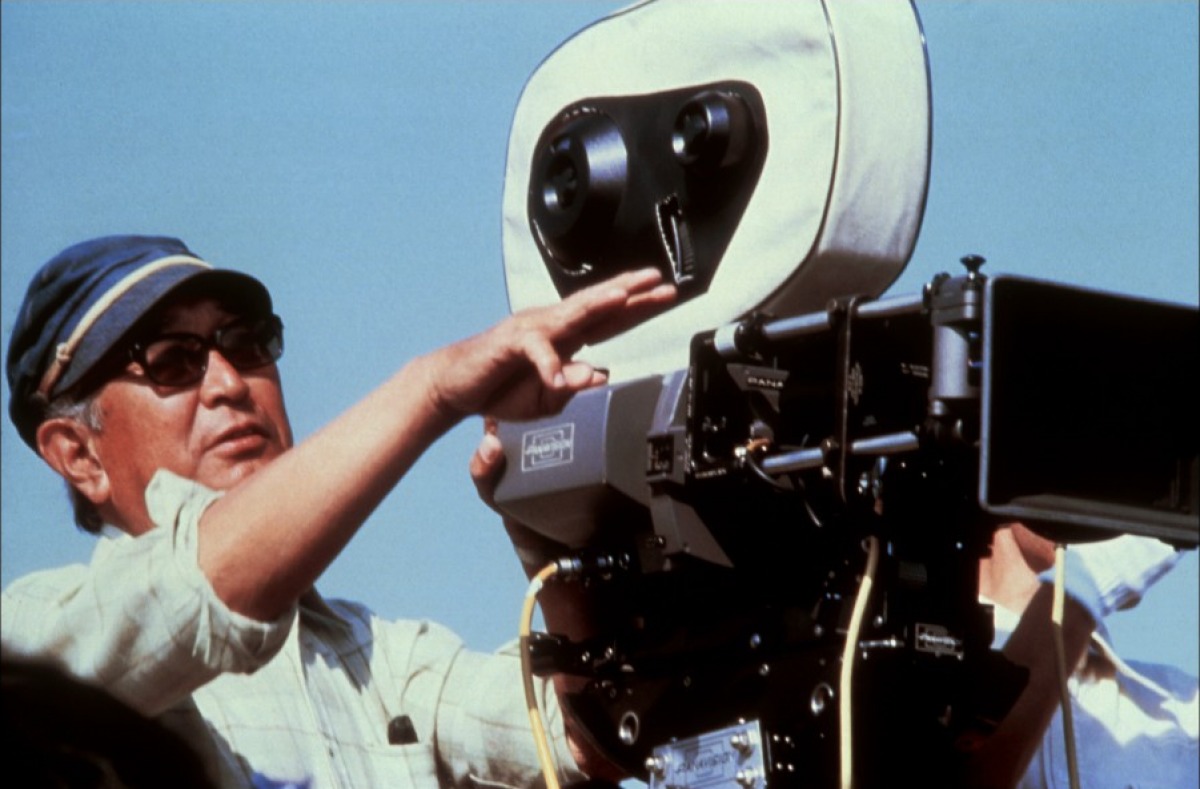

10. Akira Kurosawa

While Yasujiro Ozu made vibrant but modest films about 20th Century Japanese life, his contemporary Akira Kurosawa had his sights set on something much greater. Where gendaigeki refers to contemporary drama, jidaigeki refers to period drama; where Kurosawa predominantly thrives.

With his film Seven Samurai, Kurosawa is widely credited with the invention of the modern action movie, with its plot of a sage veteran warrior assembling a rag-tag bunch of misfits clearly mirrored in The Magnificent Seven all the way to A Bug’s Life.

His film The Hidden Fortress is often viewed as a narrative predecessor to the first Star Wars film. Through his modus operandi of running western art themes through a Japanese filter, Kurosawa also pioneered several other action tropes through his use of slow motion and the modification of filmmaking trends typically only seen in American westerns.