The cliché generalization “the sequel is never better” has been disproven enough times that it has lost its credibility. The best sequels, however, are often direct follow-ups to the original. There are plenty of Part Twos that hold their own or more against their respective Part Ones – “The Godfather: Part II,” “The Dark Knight,” “For a Few Dollars More,” and “Terminator 2,” just to name a few.

The genuinely good threequel is more elusive. Here is a list of fifteen good – if not always genuinely great – threequels that deserve to be mentioned in the same sentence with their predecessors.

Mild spoiler warning: I often hint at the endings of films but rarely give them away entirely.

15. The Dark Knight Rises (2012)

“The Dark Knight Rises” is undeniably the messiest episode of Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy. But following up the genre-transforming “Batman Begins” and the even more genre-transforming “Dark Knight” is no easy task, and so regardless of its flaws, this conclusion to the trilogy can still easily hold its own against most modern superhero movies. Eight years have passed since “The Dark Knight,” and Bruce Wayne has given up the Batman gig.

Like all retirements from crime-fighting, Bruce’s retirement must be interrupted, and the interruption here is the arrival of Bane, a menacing revolutionary who exploits Gotham’s poverty and crime rates to advocate a terroristic societal leveling that involves sentencing the upper class to death.

Sure, “Rises” is bombastic and often poorly paced. Its predecessors had a fine-tuned balance between introspection and spectacle, and in “Rises,” the scales tip toward the latter, propelled in that direction by atomic bombs and exploding football fields.

But the astounding set pieces are interspersed with more contemplative moments, like the scenes where Alfred advises Bruce to continue giving up the Batman gig. And toward the end of the film, it’s difficult not to be moved by Gotham finding hope again.

14. Lady Vengeance (2005)

The films of Park Chan-wook’s Vengeance Trilogy are linked not by story but by theme: the notion that vengeance is ultimately futile but nevertheless highly entertaining to watch. “Lady Vengeance” opens with Lee Guem-ja being released from prison after a thirteen-year stint for a murder she did not commit. She sets out to exact revenge on the man truly responsible for the murder, reuniting with her now-adolescent daughter along the way.

“Lady Vengeance” is less bleak than “Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance” (the first entry) and less complex than “Oldboy” (the second entry), but Chan-wook’s violent energy remains on full display, at least until the surprising restraint of the final scenes.

It’s possible to identify parallels to other revenge flicks – such as the mother-daughter reunion that echoes Tarantino’s “Kill Bill: Vol. 2” or the snowy final scene that has glimmers of Fujita’s “Lady Snowblood” – but Chan-wook’s resolution of Guem-ja’s retributive quest feels entirely unique. Guem-ja finds other vengeful parties with which to share the responsibility of vengeance, which allows the violent energy to diffuse.

The violence becomes a matter of calculation rather than unhinged rage – a matter of plastic bodysuits and off-screen sound effects rather than freely splattering blood. Chan-wook allows us to appreciate the futility of revenge by refusing to let us enjoy it.

“Lady Vengeance” is not an elaborate, almost Shakespearean tragedy like “Oldboy,” but it may be the most mature film of the trilogy. It is the only entry that stops reveling in the visceral pleasure of revenge for long enough to genuinely anticipate the possibility of a peaceful life.

13. Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985)

Alternately called the worst of the series and – according to Roger Ebert – “one of the best films of 1985,” George Miller’s “Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome” departs from “The Road Warrior” just as much as “The Road Warrior” departed from the original.

While “Thunderdome” does contain one of the elaborate vehicular chases for which the franchise is famous, the most memorable aspect of the film’s dystopian landscape is Bartertown, a poor development built mostly from salvaged metal. The town is in the midst of a power struggle, and Max gets caught in the middle, of course.

After a turn in the Thunderdome, which is a sort of amalgam between a cage and a gladiatorial arena, Max ends up exiled into the desert and adopted by a Lost Boys-style band of teens and children who live in an oasis.

From its post-apocalyptic production design to its creative action sequences, “Thunderdome” is just as visionary as any other film in the series. Miller’s singular imagination is on full display here, and like the makeshift vehicles that the characters of “Thunderdome” fuse together from spare parts, the film feels like a hybrid – a mad cross between spaghetti westerns, punk fashion, “Peter Pan,” and something we’ve never seen before.

12. Die Hard With a Vengeance (1995)

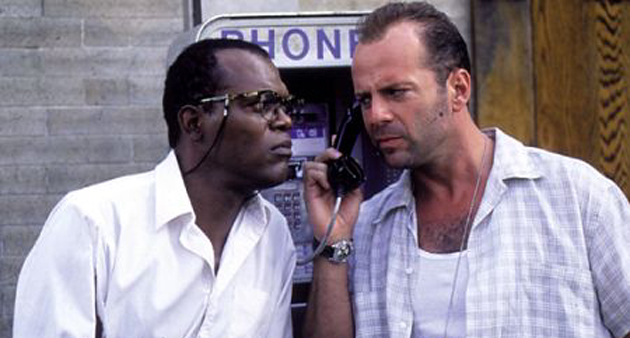

Gone are the claustrophobic settings of the first two films, replaced by a wild game of Simon Says that leads the film’s characters all over New York City. The Simon giving directions is Simon Gruber, out to get revenge for the death of his brother Hans in the first movie. This time around, Bruce Willis’s John McClane is joined by reluctant shopkeeper Zeus Carver, played by Samuel L. Jackson.

Willis and Jackson have a semi-antagonistic sort of buddy-cop chemistry that keeps the film dynamic, as if the tense races to stop bombs from detonating in various parts of the city aren’t dynamic enough. Save for the anticlimactic pacing of the ending, the film is suspenseful throughout, filled with enough ridiculous stunts and vehicular mayhem and amusing banter to make it one of the more entertaining action flicks of the 90s.

11. Goldfinger (1964)

There’s not a bad entry in Sean Connery’s string of pre-Lazenby James Bond films, but “Goldfinger” is rivaled only by “From Russia With Love” as the best. Bond must stop smuggler Auric Goldfinger from using a bomb to contaminate the gold depository at Fort Knox, an evil plan which is quite believable in comparison to the grand, often nuclear and/or world-dominating schemes devised by the villains of the Roger Moore era (see “Moonraker”).

This is not the only sense in which “Goldfinger” feels restrained; it also largely avoids the exotic locales that are an integral part of the Bond formula. Much of the film takes place in and around Fort Knox, and with all due respect to Kentucky, nondescript semi-urban areas of the southeastern U.S. rank lower on the intrigue meter than tropical islands and alpine fortresses.

But this is not a criticism. “Goldfinger” uses its restraint to set itself apart from other entries in the series, staying more grounded than, for instance, Bond’s missions to stop Blofeld. That’s not to say that it forsakes the trappings of the spy genre.

On the contrary, “Goldfinger” contains some of the most iconic sequences and characters of the entire series – from Oddjob and his razor-sharp hat to the laser that nearly slices Bond in half to the memorable image of Bond’s short-lived romantic interest Jill dead and covered entirely in gold paint. “Goldfinger” plants the improbable elements of the Bond formula into a suspenseful plot that feels quite plausible in comparison to the Roger Moore films.

10. The Bourne Ultimatum (2007)

The Bourne trilogy is a cut above its companions in the shaky cam thriller genre, though it is undeniably responsible for the proliferation of that particular cinematographic choice.

The trilogy is arguably the first great post-9/11 action series; its relatively grounded stunts and attempts at realism resist the cheerful implausibility displayed by many of the most influential 90s action films – such as the cheerfully implausible “True Lies,” “The Rock,” and “Face/Off,” to name a few.

In the Bourne films, the threat feels realer and closer to home, due in part to the top-level, top-secret counterterrorism operations on display and in part to the rough camerawork and brutal hand-to-hand combat.

In “Ultimatum,” Jason Bourne is finally coming close to learning his real name and maybe even exposing the illicit CIA-operated black ops programs that left him near-dead in the first place.

Amidst the tense cat-and-mouse chase sequences and impressive fight scenes, “Ultimatum” does find time for some deeper thematic concerns: the defining features of identity, the ethics of behavior modification, and the political corruption caused by excessively utilitarian moral frameworks. “Ultimatum” is a thrilling conclusion to the trilogy that demonstrates above-average intelligence for its genre.

9. The Silence (1963)

Ingmar Bergman’s unnamed trilogy consisting of “Through a Glass Darkly,” “Winter Light,” and “The Silence” is probably the most loosely connected set of films on this list. The link between the films is purely thematic, with all three confronting spirituality (especially faith) and emotional isolation. Bergman identified the titular silence as the silence of God, though this is the member of the trilogy in which the struggle with religious faith is least apparent. God has already left, and all that remains is his silence.

Bergman uses this negative space as the setting for a story about two sisters: Ester, a translator who is gravely ill and uninterested in sex, and Anna, who is younger, healthier, and more sexually minded. Bergman constructs the film around the dichotomies the sisters represent –mental vs. physical, isolation vs. togetherness, sickness vs. health.

Anna’s ten-year-old son Johan seems less like a conduit for Bergman’s ideas about alienation and duality, as he spends his time wandering around the hotel rather than ruminating on sex and death. Whenever the film feels in danger of floating too far into Bergman’s abstract tendencies toward philosophy and psychology, Bergman reminds us that the story is tethered to Johan’s ability to look past the problems with which his mother and aunt wrestle.