The seed of existentialism is often addressed to Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard, who described the human condition as an individual struggle against time in which angst plays a primary role.

Since Kierkegaard, many philosophers have tackled the human condition through philosophy to try to understand the nature of suffering, fulfillment, etc. By the time that cinema became a mature art form, it also started to display the philosophical preoccupation through the experiences of the characters and by the way they communicated.

Films that displayed an individual with a subjective struggle against society, truth, and more are examples of the great degree of depth that a film can achieve in the portrait of the human condition.

These films are found in several kinds of styles and with several subjects, but there is always the constant questioning of the reality in relation to the individual. Here is a list on 10 great films that display an existential crisis, crafted by greatest legends in the film world.

10. Hamlet Goes Business

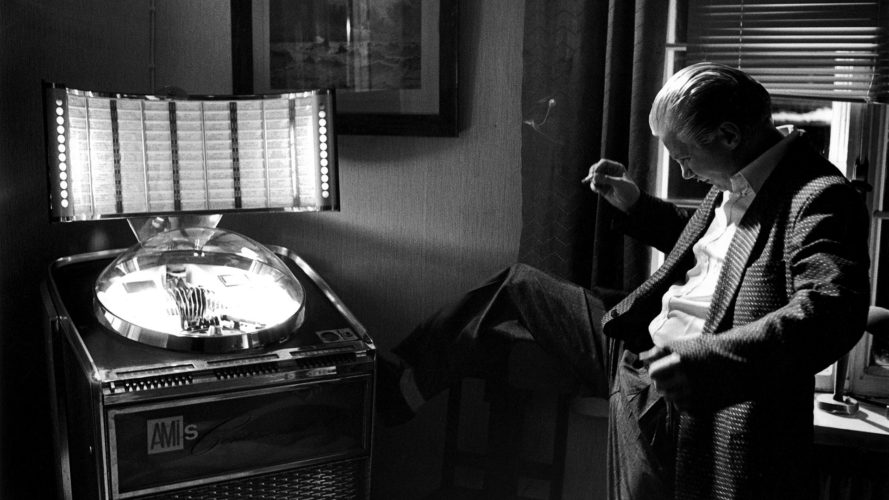

Aki Kaurismäki’s fourth feature film is an adaptation of the classic Shakespearean drama, released in 1987 and staged within the industrial empire of a Finnish group. The adaptation that Kaurismäki made is one that is very conscious of the particularities of film form, without the classic Shakespearean dialogues and monologues; the film relies much more on silent contemplation and gestures to display the inner struggles of the character. The film shows the classic characters in contemporary scenery and shows the dilemma and transformation of Hamlet without any monologue.

The character of Hamlet is one with a profound crisis; on one side, there is his dilemma of vengeance that adds to the existential void in which he feels. Hamlet is an alienated character who transforms from an inactive observer to a destructive force that ends with everything he loves and hates.

By the end of the film, Kaurismäki creates a wonderful epilogue as he presents one of the factories inherited by Hamlet while a song plays. The song fills with a sense of the adaptation as a meditation on the fatality of human existence, and whether history is condemned to repeat itself.

9. La Dolce Vita

It was in 1960 when Federico Fellini displayed his highly personal and mesmerizing style with the first of his masterpieces, “La Dolce Vita.” The film is a group of episodes in the week of Marcello Rubini (Marcello Mastroianni), a journalist immersed in the glamorous and eccentric world of modern Rome.

Throughout the film, Marcello is in a constant search for fulfillment that is never satisfied. He tries to satisfy himself through several mediums, but the void in him and his existential malady never goes away as he keeps on in the degraded world of “La Dolce Vita.”

The episodes of the film are crafted with the unique and strange style of Fellini, full of provocative dialogue, rarefied atmospheres, and symbolic interactions. In this film, Fellini creates an allegory of the modern man in an absurd search for fulfillment in the world of pleasure and spectacle.

The film builds up to a memorable finale where Marcello is shown in relation to a young and innocent girl, a character who remains unreachable to him (he is not even able to understand her) due to the different natures of the worlds in which they live.

8. F for Fake

More than 30 years after the outstanding “Citizen Kane,” Orson Welles proved to the world that he was still able to create unique and original films with his 1973 unclassifiable film “F for Fake.”

With the affirmation that “a magician is just an actor playing the part of a magician,” Welles starts a reflection (or is it a fraud?) on the nature of fakery and its relationship with art. One of the great subjects of existential crisis is the nature of truth and reality, and in this film these topics are tackled with an uncompromised and poetic approach that was only achievable by the genius of Welles.

With portraits of legendary art forger Elmyr de Hory, himself and even Picasso, Welles meditates on the human condition as it relates to art. He questions the true value of art and authorship as he tries to reveal where the true value does resides. Guided by the personality of Welles in complete control of the film, the viewer who enters an existential crisis as our conception of art, authorship and truth is challenged by the “magic” that Welles does with film language.

7. What Are the Clouds?

Adaptations of Shakespearean dramas always involve character with deep existential crises, but this short film by Pier Paolo Pasolini is one of the greatest adaptation ever made of a Shakespearean play, because it goes beyond what the play originally proposed and creates a unique experience through film language.

This is an adaptation of “Othello,” or more precisely, a film of an adaptation of “Othello.” We assist a montage of the classic play by marionettes that we see interact behind the stage to question the decisions of their characters.

The marionette that plays Othello questions both his character and the reality of the representation, and here is the existential crisis that goes beyond the jealousy of Othello. Interacting with the marionette of Iago, Othello questions the reality of the play as he is forced to play a role for which he not sure certain.

As the short film goes on, the play is interrupted, getting both marionettes out of the theater and allowing them to see the clouds. This experience of reality and fiction is the subject of the crisis wonderfully depicted by the unique Pasolini.

6. The Meaning of Life

The films that Monty Python made were so enjoyable for not only their cynicism and inventiveness of the group, but also for the deep understanding of society and philosophical problems that the group displayed in the films.

“The Meaning of Life” is a group of thematic sketches that tackle different aspects of human existence, such as growing up, sexuality, or religion with an acute sense of humor. The film reveals the absurdity and contradictions of many of the ways in which humanity tackles these matters. The film is a complete tour of the human experience that does not leave anyone safe from ridicule.

The lightweight humor of the Pythons is displayed in one of the sketches where they finally decide to reveal the “meaning of life.” Delivered without any kind of seriousness, the answer is something like “try to be nice to people, avoid eating fat, read a good book every now and then, get some walking in, and try to leave in peace and harmony with people of all creeds and nations.”

This “answer” is delivered with great irony after the previous sketches have shown how human existence is indeed extremely complicated, but showing that these complications are mostly absurd. Here is a film that indeed displays an existential crisis, but does so with a great deal of humor that puts into perspective the solemnity with which we address this crisis, sometimes doing so with wonderful musical numbers.