Much of the conversation surrounding the “best of” when it comes to this decade has seemed sort of futile since there was so much of the decade still left to come, and seeing where we are now as compared to where we were in 2010, that optimism, that held the inherent expectation that what would come in the years left in the decade would far surpass what came before it, is hardly one that was baseless.

Yes, films in every genre have made strides towards the better and the greatest accomplishment, perhaps, has been that of independent cinema, which has really taken over the filmmaking scene in terms of quality, ability to take incredible risks and inclusion of filmmakers who, within the studio system would have possibly never gotten an opportunity.

But when one realizes that we are in 2018, and the decade is almost over, the declarations and claims of “best of” seem to contain much more gravity than they did before, and subsequently, come with much more consideration.

So, yes, you are welcome to mock the idea that a release as recent as Ari Aster’s “Hereditary” can be hailed by anyone as the greatest of the decade in the horror genre, or any genre for that matter, but it comes with a realization that even though the game in horror and its ability to gel so fluidly into any other genre and sneak up on us has been upped quite a bit by the filmmakers this decade.

There is quite simply nothing that beats the frenzied, blood-soaked, despair-ridden anxieties of Aster’s masterpiece when it comes to the advancement of one of the most naked genres of cinema – one that is so dependent on and feeds off of the experience of its audience that at some point all literary aspects need to be stripped away and the pure sensation of being pulled into the darkness is required to overpower you for you to feel impressed by what the filmmaker has pulled off.

Many ghost stories and psychological anxiety-fests this decade have employed and twisted the generic tools of cinematic horror for their use this decade and come the other side either horribly unbearable with their predictable set of jump scares with even worse executions (“Don’t Breathe” being the typical example of a film where a fascinating idea is bogged down by abhorrent filmmaking), or be so hypnotic you feel as if you have been immersed into the film’s universe of dread and catastrophe completely (“It Follows”, “The Witch”, “The Babadook” being prime examples), or fall somewhere in the middle where the thrills are exquisitely laid out, but the affair on the whole is pretty much forgettable (“The Conjuring” series and “A Quiet Place” being two that fit that box.)

Aster’s family-drama-turned-nightmare-saga is somewhat beyond these characterizations. It is perhaps, in effect, the closest any film this side of the century that has come close to the paralyzing fear of a nightmare you cannot escape because your limbs just won’t work since the Wendy’s scene in Lynch’s “Mulholland Dr.”, and that’s saying a lot.

So with that, here are 10 factors that are an attempt to deconstruct the magic of “Hereditary.” Needless to say, spoilers galore.

10. The cinematography

There is a bleakness with which “Hereditary” is shot; its visual tapestry allowing for a complete bathing of the audience in dark, sinister, moody and placid undertones. It’s shot in digital (Arri Alexa Mini), so even in low light scenes, there isn’t total darkness, but a washed-out, stone-coloured stillness that is as unnerving as it is intoxicating. It crawls under your skin, without so much as whispering its presence, and stays there until you can shake it off, which, with its brilliant use of solid, lack of eye-popping colour makes it virtually impossible.

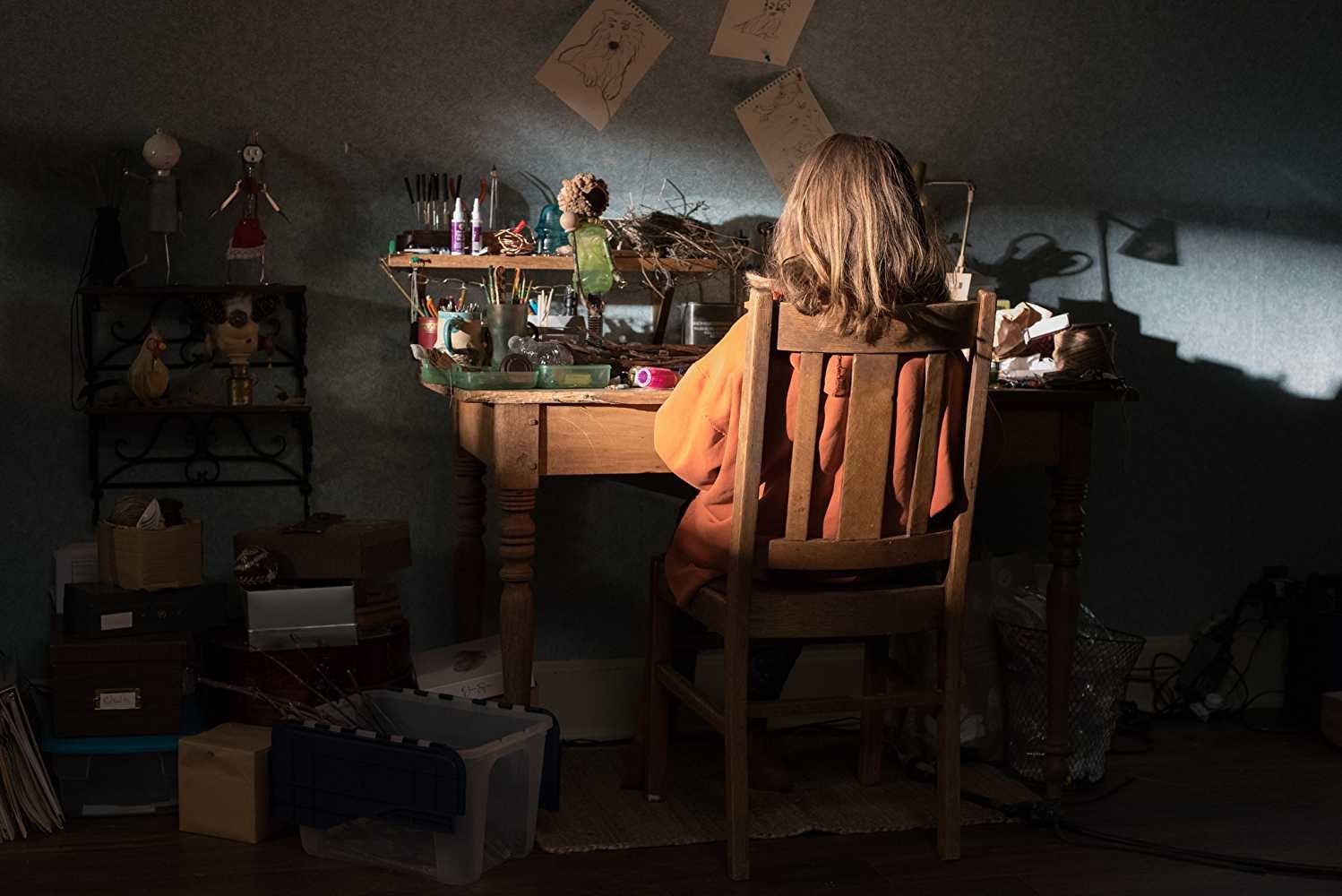

Another aspect of “Hereditary’s” lucid, sour, but somehow simultaneously piquant camera work is how it zooms in and out and uses perspective to capture its characters. Annie at the support group meeting is a perfect example of this.

When she begins speaking about her turmoil, the camera is close to her face, ravishingly displaying Toni Collette’s perfectly timed monologue, but when, near the end of it, when her worries seem to be leaning towards the irrational and exaggerated, and her heaviness seems like something that she has always carried with herself, almost by choice, it zooms out, and we view her through someone’s shoulder, and of course, we later find out who is observing her in that meeting and the way the camera looks upon her almost seems like we are inflicting a sort of cruelty on her by looking at her this way. It’s so carefully studied that it’s nearly impossible to pick up on your first watch.

There is another great shot of Annie as she walks towards Joan’s door towards the end of the film, attempting to confront her about the things happening to her son. It’s a complete 180° turn and the image is reversed as if the lens is perverted enough to enjoy her plummeting towards desperation this way.

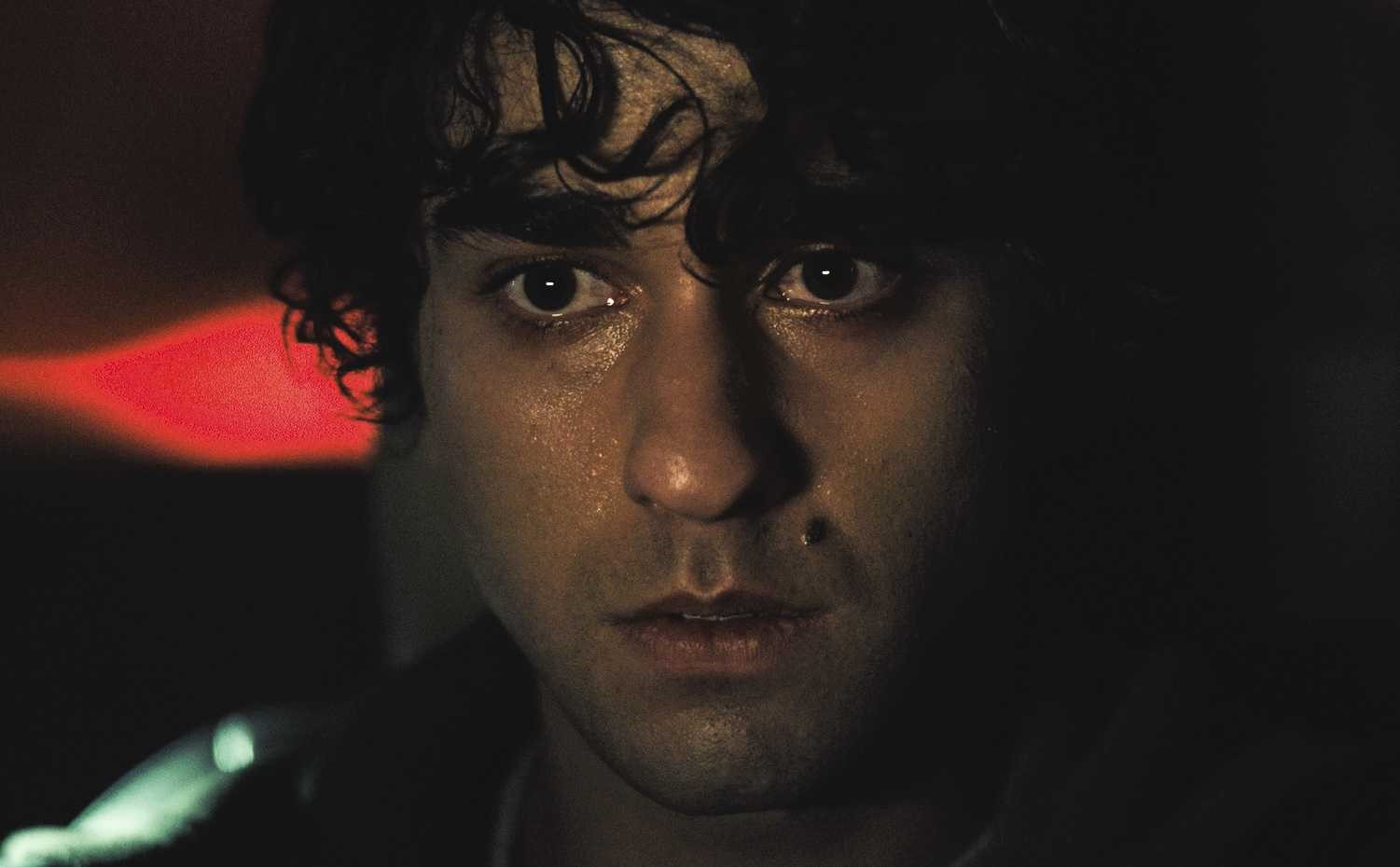

Reflections play a strong role in some of the most haunting scenes in the film – Peter looking at a freakishly happy reflection in his classroom, Joan telling Annie that Charlie isn’t gone yet, and they work to pull you to deeper into the film because even the shadows shimmer with such intensity in this one.

9. The character of Charlie Graham

Charlie Graham isn’t your typical horror movie kid. She’s not smart, or happy, or even someone you root for. All that is she is can be described in one word: transfixing. There’s something about the way she talks, as if hiding something every time she opens her mouth, not to protect herself, or to be nice, but almost as if to protect her family.

There is no spark in her eyes as she draws, or works on a toy, or cuts a dead bird’s head off, it’s all like a chore she’s both deeply engrossed and couldn’t be more disinterested in. It’s a double whammy actors twice actor Milly Shapiro’s age would have a hard time pulling off this successfully.

Her unusual face and even more obscure, secretive demeanour hangs over the film like the stench of death that wouldn’t go away, and because you relate so deeply to Annie and the way joy has been completely sucked out of her life, that face and that presence is indispensable.

In the bleak emptiness that surrounds the three characters after Charlie’s death, her “cluck” is as much filling the gaps left by her absence, as it is bone-chilling in the way most horror movies dream their jump scares are.

Her demise itself is so unimaginably shocking and so left-of-field dark that it sinks its teeth into you and doesn’t let go. The grief felt by Annie, Peter and Steve transports into you so effortlessly that by the time you realize how heavy your chest feels, you’re already breathless. It is tragic, demonic and so masterfully executed, that in its cocktail of rage, grief and inevitability, leaves you feeling possessed by its sheer awfulness for the rest of the film and for days after.

8. The use of music

As the foregoing text might indicate, there is a heart-stopping dread pulsating through “Hereditary” that makes it such a delectable psychological drama. Most of that dread it owes to its dizzyingly stoic and concertedly hypnotic soundscape – a large part of which is the score by Colin Stetson, the famous saxophonist whose clarinets and basses will keep ringing in your ears for hours after.

It lays the groundwork for the characters and introduces them all with the most foreboding and the least generous of thematic notes, as if trying to quietly perfume their consciousness with evil. Its mood is at times calm and restrained and at others calling out to wolves. It’s both kinetic and rapid and yet, silent and watchful.

Stetson’s greatest achievement perhaps is the way his score envelopes the character of Charlie with such mystery and fear. It makes her both immensely tragic and figure of unimaginable darkness just bubbling underneath the surface.

It’s harrowing and propels you to look deeper into Milly Shapiro’s static gaze, and of course there are no clear answers, only the most incredulous sense of macabre anguish. And in the end, when the spirit of Charlie (read: Paemon) is finally at peace, it feels joyful and grandiloquent, as if taunting us for sustaining hope of any contentment.

7. The subversion of expectations

Much of the criticism for “Hereditary” is focused on how it follows the predictable course of a conventional, old-school horror film. Detractors, who say it is scary only for those who aren’t, to quote one critic, as “Immersed in horror” as they are, have unfortunately not allowed themselves the opportunity to let its singular hysteria creep under their skin. They are viewing it, quite simply, from the outside in.

What lies at the core of the originality with which so much of “Hereditary” is constructed, is the ability to not let knowledge of how the events in the narrative might unfold, or even a premonition of it, deter it from creating an atmosphere so sombre and grave that it if inherited in its full gravity, it will claw away at you, no matter how easy it is to guess which turn it will take. It colours its melancholia with such a desolate, unforgiving tone, that there is no way out.

Yes, it frequently resorts to tools used previously by horror classics, and it is unabashed in drawing influence from “Rosemary’s Baby”, “Don’t Look Now” and “Cries and Whispers”, but it also, like those films, carves something deep inside you, pushing you into some sort of pool of depravation where the only prevailing sense is of inescapable dread.

It is not made for stunning you into silence every few minutes, and its scares might look sparse on the surface, which has led to many decrying its acclaim. But I agree with Telegraph critic Robbie Collin who says, “The comedian Norm Macdonald once said that the perfect joke would be one in which the set-up and the punchline were identical. I’m becoming increasingly convinced that something very similar holds for horror: being blindsided by fright might be fun in the moment, but it’s the scares you can see coming that last.”

6. The lack of horror movie tropes

This might seem ridiculous considering the unconventional horror that has come out this decade, but still does not reduce the validity of “Hereditary’s” claim that it might be one of the most original films of the last 10 years, let alone a horror one. And yes, cults and séances have become staple for horror films, but the way they are used in this film defies all categorization. The dread doesn’t come from the announcement of their presence, but the weight with which the film makes you feel like they have been here for years.

“Hereditary” does not bring its innocent, naïve protagonists into a new, unfamiliar setting and let demons loose upon them as we watch over them with pity and mild amusement. It somehow conjures up the devil from within the roots of the house they have always lived in and from within their family members, which consequently, makes so much of their pain and grief internal and personal; escalating our fears to imagine the worst.

It crafts each detail – the mother’s possessions, Annie’s minimalist creations, Steve’s exhaustion, Peter’s constant anxiousness with great care and passion, and with equally intoxicating authority and ambition. It doesn’t demand shocks and cries and hysterics, it demands pain and misery and wrenching devastation with an almost beautiful stillness. It’s a majestic feat to pull off, and this one does it so effortlessly that the meticulousness is never apparent.