Cult films regularly pride themselves with being eccentric, controversial, obscure, offbeat, and often unmarketably strange. Cult films also, unfortunately for fans waiting in the wings, often struggle to get noticed at all, let alone find an appreciative audience, or any kind of financial success.

The short list that follows consists of films you may have missed that have been met with adoration from those chosen few that have found them. They’re not bombs by any means, but most people will have to do a little scratching to dig them up.

Hopefully then, this will be a sort of shortcut for any adventurous moviegoers who want something both engaging and utterly unique. Who knows? Your new favorite film may await!

10. Hobo With a Shotgun (2011)

With a title like “Hobo with a Shotgun” you’d better expect a crass, off-color, gloriously off-kilter, and utterly over-the-top exploitation experience, because that’s exactly what you get. This deranged black comedy/horror-thriller doesn’t just leave good taste at the door, it gouges out its eyes and defiles it’s still kicking corpse as director Jason Eisener and writer John Davies go hardcore, with shotguns ablazin’.

Inspired by the mean-spirited trailer of the same name featured in the Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez omnibus film Grindhouse (2007), and the South by Southwest Grindhouse contest that coincided with it, this is a gory spectacle for exploitation fans.

Rutger Hauer is the eponymous homeless avenger who takes on the Drake (Brian Downey), a sadistic crime boss –– sadistic being an understatement –– and his cruel sons (Nick Bateman and Robb Wells), who rule over Hope Town with an iron fist and a raised middle finger.

The antithesis of cinematic subtlety, this gloriously gruesome homage to low-budget horror is actually pretty damn enjoyable if you can get past the deliberately vile content (mistreated hookers, horrible pimps, a pedophile dressed as Santa), blood-splattered gore, colorful dialogue, and guiltily enjoy the revenge-fuelled awfulness of it all.

9. Taxidermia (2007)

Hungarian surrealist György Pálfi’s second film was the visually striking and altogether outrageous generational drama Taxidermia. Displaying his signature imagination and wit, the film continues Pálfi’s obsession with machinery and processes, and while not always comfortable to watch, the creative flourishes at the film’s dark heart make it worth staying the course.

Divided into three segments over three generations, Taxidermia is a triptych that moves like this: a World War Two-era section gives us grandfather Morosgoványi Vendel (Csaba Czene), a sexually frustrated orderly whose bizarro sexual fantasies are rather outlandish; the second section involves Vendel’s morbidly obese son Balatony Kálmán (Gergely Trócsányi), who to be a champion speed eater; the final segment focuses on Kálmán’s child, Balatony Lajoska (Marc Bischoff) who becomes utterly obsessed with taxidermy. Lajoska’s ambition is to stuff his own body before he dies. Does he succeed? Let’s just say the final scene is something of a jaw-dropper.

Pálfi based Taxidermia off of two stories by noted magical realist writer Lajos Parti Nagy (the taxidermy sequence that stitches them all together is wholly of Pálfi’s own invention), and the resulting film, a miasma of body horror, aberrant desires, and flame-shooting phalluses (yes, you read that correctly). Few filmmakers are as imaginative and messed up as Pálfi, and that’s a sincere compliment.

8. Schizopolis (1996)

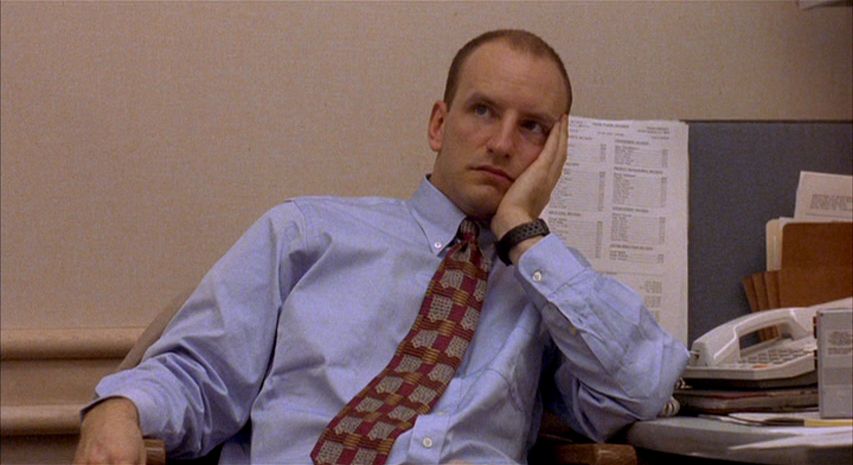

This seriously experimental comedy from Steven Soderbergh (Ocean’s Eleven [2001], Logan Lucky [2017]) is a non-linear perplexity like its title suggests. A strange, at times unintelligible, non sequitur-spewing affair, Schizopolis is also a shit ton of fun.

Shirking no responsibilities whatsoever, Soderbergh directs, writes, stars (in multiple roles, no less), edits, and films the decidedly unconventional tale; a pointed thrust and parry at society’s ills, in a three-pronged self-aware narrative.

Told from at least three differing perspectives (not counting the viewer, who is frequently implicated in the proceedings and addressed directly), Schizopolis details the life of office drone Fletcher Munson (Soderbergh), who works for an L. Ron Hubbard-type guru, and also depicts the duplicitous goings on of Munson’s dentist doppelgänger, Dr. Jeffrey Korchek (Soderbergh), an artless exterminator named Elmo Oxygen (David Jensen), and Munson’s liberated wife (Betsy Brantley) also referred to, in vulgarized fashion as “Attractive Woman #2”.

Schizopolis works as a comedy and as a satire, in spite of it’s self-destructive tendencies and deliberately serpentine storyline. It’s the type of film that alienates a large portion of the audience, but the other portion will love it and find it imminently quotable, perhaps obsessively so.

7. Insignificance (1985)

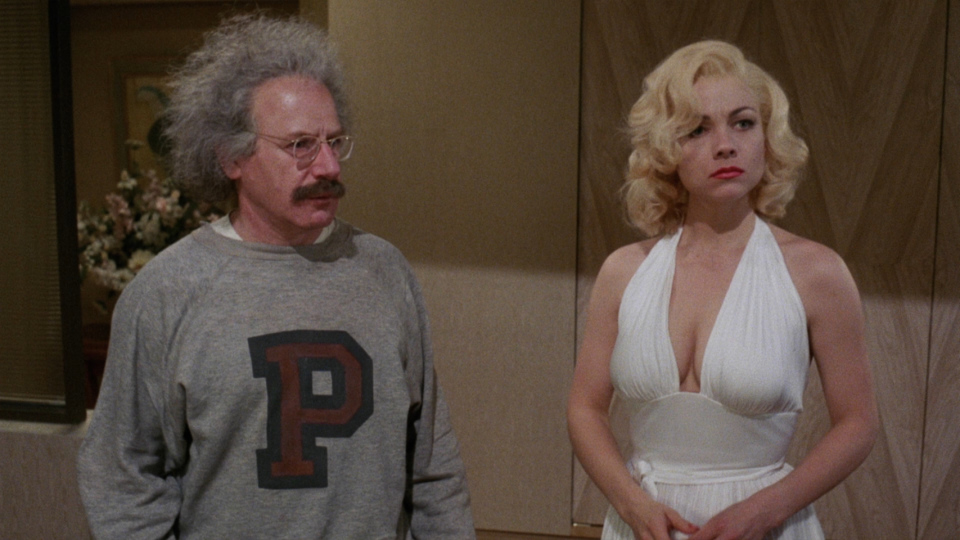

Adapted from Terry Johnson’s play, this film from Nicolas Roeg (Don’t Look Now [1973], The Man Who Fell to Earth [1976]) occurs on a summer night in 1954, set in anonymous hotel rooms where the lives of four iconic figures; Marilyn Monroe (Theresa Russell), Albert Einstein (Michael Emil), Joe DiMaggio (Gary Busey) and Joe McCarthy (Tony Curtis) – though in the film they are simply and slyly referred to as the Actress, the Professor, the Ballplayer, and the Senator – fatefully intersect.

These recognizable popular culture figures, in typical Roeg fashion, riff on grandiose ideas and floundering emotions. What begins as trivial digressions gains momentum and significance, buoyed by stellar performances (like Curtis’s McCarthy, witch-hunting endlessly in his mind, or Russell’s Monroe, who, despite her ditzy dilettante routine can still teach Einstein a thing or two about relativity).

On the surface Insignificance may not be the exacting pedigree of Roeg’s recognized masterpieces, but it’s still a vast, ingenious allegory on fame, life, love, obsession, jealousy, and substantially so much more. Don’t miss it.

6. Poison (1991)

Todd Haynes (I’m not There [2007], Carol [2015]) rushed onto the stage as a New Queer Cinema trailblazer in the dizzying 1991 debut, Poison. This audacious, confrontational, and uncompromising portmanteau triptych takes on three wholly different genres (faux documentary, gay prison romance, and 1950s sci-fi horror B-movie), drawing perhaps most notably from French iconoclast Jean Genet’s lurid BDSM-addled poetic writings.

The common thread that sews these stories together rests in the dissection of traditional attitudes on homosexuality, and social panic, with results that move from subtle to extreme as familiar modes, methods, and archetypes get reworked and regenerated right before our eyes. Even today, over 25 years on, it’s rare to see such contrastingly delicate, lithe, and polemical designs in a single film. Poison is powerful stuff.