Admittedly writing and publishing a cinema list that, in this case, purports to be a definitive listing of “the 25 Best Foreign Language Films of All Time” is clickbait that borders on trolling. Well, that isn’t that case at all, despite the fact that numerous international favorite filmmakers didn’t quite make the cut (alas, Robert Bresson, Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, Abbas Kiarostami, and Kenji Mizoguchi are amongst the luminaries who are not represented here) and more than a couple noted classics are also absent (8 1⁄2 , Berlin Alexanderplatz, M, and The Rules of the Game are not listed below). No, the ambitious list that follows is not going to please everyone but it does contain 25 masterpieces from the those who rank amongst cinema’s finest artists.

So please, enjoy the films that follow, seek out and view those that are new discoveries, and list your favorites that slipped by us in the comments section below.

25. Chungking Express (1994)

Wong Kar-Wai’s ecstatic romantic comedy drama casts C-pop superstar Faye Wong in one of two impossibly energetic, color-saturated, and highly stylized stories. With a music video aesthetic, this vibrant, visceral film is also buoyed by its use of music (will Mamas and the Papas smash “California Dreamin’” ever be used to such glorious effect ever again?), adding the occasional clandestine dip into almost surreal reverie.

Chungking Express is hard to forget — romantic yearning and sacrifice both poignant and impassioned frisk with the facile uncertainties of youth and acquired wisdom — amounting to Wong’s first real masterpiece.

24. Raise the Red Lantern (1991)

Zhang Yimou confirms his status as one of the most masterful and artistic filmmakers of all time with his striking and stirring picture from 1991, Raise the Red Lantern. The final film in his loose trilogy that began with 1987’s Red Sorghum, and continued in 1990’s Ju Dou, this is the bleakest of these crimson-hued melodramas.

“People have compared Gong Li and Zhang Yimou to Dietrich and von Sternberg, but for me the Chinese couple is even more impressively cryptic in their design and Raise the Red Lantern is their best,” said actress Isabella Rossellini in a BFI discussion of her favorite films, adding that “…it feels like the history of a country, a culture and even a gender are all present in any randomly chosen frame of this serene and gorgeous poem.”

Filmed in three-strip Technicolor, a process long abandoned by Hollywood, which acquiesces a richness of reds and a luxuriance of yellows no longer achievable in American films, Zhang’s historical heartbreaker somehow sidesteps maudlin sentimentality while still maximizing its titular red blush. One could argue that the flushed palette matters as much as Songlian (Gong Li) does to this wintery tale of stifling coldness and bitter release.

Raise the Red Lantern is a lawful and lionhearted classic, and an absolute gem.

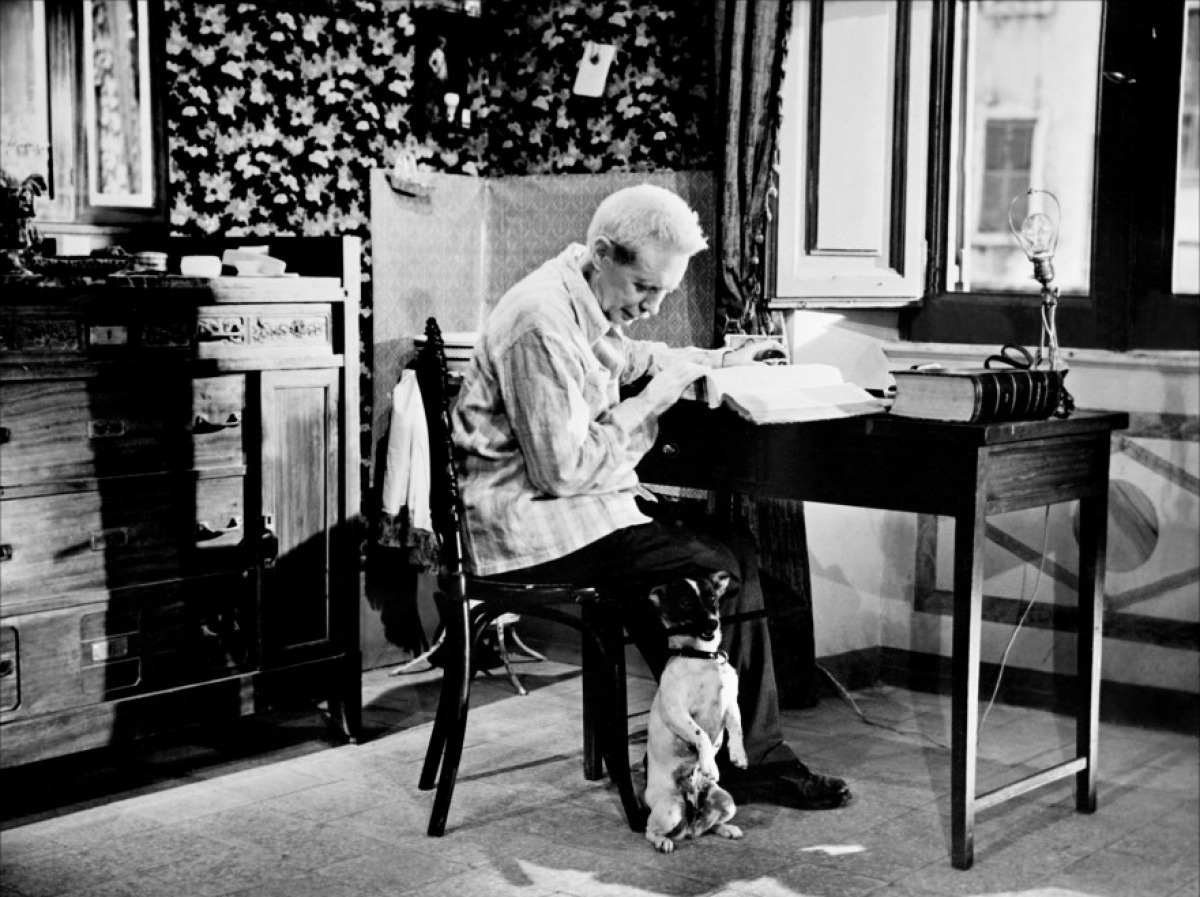

23. Umberto D. (1952)

Ingmar Bergman has said that Vittorio De Sica’s “Umberto D. is […] a movie I have seen a hundred times, that I may love most of all.” An Italian neorealist masterpiece from a true innovator of the form, De Sica (whose 1948 classic Bicycle Thieves also occupies this very list) crafts a film of subtle elegance with a Chaplinesque tale of a poor old man out to protect his dignity during the course of the often degrading everyday.

Carlo Battisti, a non-professional actor, is absolutely brilliant in the titular role of Umberto Domenico Ferrari, an elderly pensioner well below the poverty line, living in Rome, he struggles to keep his rented room and to care for his beloved dog, Flike.

Antonio Belloni (Lina Gennari) is the landlady who insists upon her 15,000-lire rent by the end of the month, or else Flike and Umberto will be out on the street. Feigning an illness to buy a little time, Umberto ends up at the hospital, leaving Flike with the pregnant maid, Maria (Maria-Pia Casilio), but when Flike runs away in search of his master, events take a turn that is damaging for Umberto’s vulnerable emotional state.

“It is said that at one level or another, Chaplin’s characters were always asking that we love them,” wrote Roger Ebert in his glowing review of the film, adding that “Umberto doesn’t care if we love him or not. That is why we love him.” And there is much to love about this beautiful little film.

22. Pan’s Labyrinth (2006)

Mexico’s Guillermo del Toro’s deeply personal dark fantasy coup de grâce from 2006, Pan’s Labyrinth is a sublime and stunningly beautiful masterpiece. Set in Spain in 1944 we meet young Ofelia (Ivana Baquero) and her mother Carmen (Ariadna Gil), who is pregnant and whose health is diminishing. The two women have just relocated to be with Carmen’s new husband, the sadistic army officer Captain Vidal (Sergi López).

Ofelia takes an instant dislike to the Captain and soon finds distraction in an ancient maze where she encounters the mysterious and otherworldly faun, Pan (Doug Jones). Pan tells Ofelia of her forgotten lineage as the lost Princess Moanna and how she must perform three potentially deadly tasks in order to reclaim her throne and the immortality that goes along with it.

Epic in scope, with a poetic Dickensian influence, tangible excitation, a fabulist, fairytale-like cognizance –– Alice in Wonderland is another obvious inspiration –– making for an elegant flight of the imagination. But make no mistake, this is no children’s movie.

The violence of the real world around Ofelia is terrifying and extreme, but del Toro, while never sugarcoating anything or Disney-fying his creations still imbues the film with a sense of wonder, danger, artistic ambition, and compelling, tragic, astounding poignancy. Not for the faint of heart no, but for the strong of imagination and for the deeply adventurous and bravely devout. Pan’s Labyrinth is a beautiful and terrifying place to get lost in.

21. Beau Travail (1999)

Loosely based on Herman Melville’s 1888 novella “Billy Budd”, provocative French director Claire Denis’s Beau Travail is almost like a work of black magic. As Salon’s Charles Taylor suggests, “[Beau Travail] is the most extreme example of [Denis’s] talent, baffling and exhilarating. I don’t know when I’ve seen a movie that is in so many ways foreign to what draws me to movies and still felt under a spell.”

Recalling his once glorious and full life, Foreign Legion officer Galoup (Denis Lavant) leads his troops in the Gulf of Djibouti. Though strict and regimented, Galoup’s life’s a happy one until the arrival of Sentain (Gregoire Colin), plants the seeds of toxicity. Feeling compelled to stop him from coming to the attention of the commandant who he admires, Galoup’s jealousy will lead to mutual destruction as gender and racial politics meld with Denis’s love of lighting, color, and unerring composition.

“So tactile in its cinematography,” wrote the Village Voice’s J. Hoberman, “so inventive in its camera placement, and sensuous in its editing that the purposefully oblique and languid narrative is all but eclipsed.”

In the years since Beau Travail, Denis has remained one of contemporary cinema’s most audacious directors, and with a ferocious talent to boot. This may well be her crowning glory and it certainly helped close out the 1990s on a terrific and terribly high note.

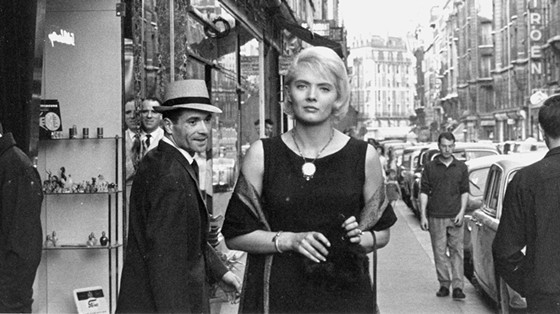

20. Cléo From 5 to 7 (1962)

Incredibly modern, even startlingly so, Agnès Varda’s second feature not only further established her international reputation, it also remains an enchanting classic of French New Wave cinema. Cléo from 5 to 7 unfolds very closely to real time as it chronicles two suspensefully sustained hours in the life of Cléo (Corinne Marchand, wonderful), a self-absorbed pop singer, as she waits to find out whether or not she has cancer.

Cléo’s anxiety heightens all of her perceptions and gives her a dazzlingly new appreciation for the beauty of the simple things and the everyday. Elegantly and luminously shot on the streets of Paris, and with cool cameos by Jean-Luc Godard and Anna Karina, this pioneering film proves to be both as influential and innovative as any from the Left Bank.

Pauline Kael famously enthused that “Varda sustains an unsentimental yet subjective tone that is almost unique in the history of movies.” Don’t miss it.

19. Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974)

Shot in a scant fifteen days, Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Ali: Fear Eats the Soul is a timeless classic, and a love story of great unshakeable power. Deceptively simple, spare and yet artful, Fassbinder’s film is technically flawless, and 44 years on, has proven to undoubtedly be a cinematic monument.

Deliberately indebted and paying rich homage to Douglas Sirk, particular All That Heaven Allows (1955) and Imitation to Love (1958), Ali: Fear Eats the Soul is a melodrama for the ages. Gaining its rich texture from the minutiae of working-class life the film stars Brigitte Mira as a sixty-something German cleaning lady living in Munich and El Hedi ben Salem as Ali, a Moroccan guest worker twenty some years her junior. Their love affair germinates amidst a climate of hostility, racism, ageism, and societal lassitude, but they stay the course, knowing that their happiness will conquer all.

This is a film that fearlessly takes huge risks, is incredibly courageous, and, when all’s said and done, attempts nothing less than to romanticize life’s rich mystery. It will surprise you in delightful ways and you’ll carry it’s warmth with you forever.

18. The Seventh Seal (1957)

A profound and philosophical classic of world cinema that unravels in Sweden during the Black Death, Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal is a masterclass in iconography, artistic vision, and the silence of God. Max von Sydow is unforgettable as Sir Antonius Block, a knight who has returned from the bloody Crusades only to find that his homeland is in the throes of an apocalyptic plague.

Challenging Death (Bengt Ekerot) to a chess match for his life, and tested and tormented over his new found belief that God doesn’t exist, how long can he evade Death and will he find redemption before it’s too late?

The New York Times scribe Bosley Crowther detailed how Bergman’s themes were enhanced by Gunnar Fischer’s sterling cinematography: “the profundities of the ideas are lightened and made flexible by glowing pictorial presentation of action that is interesting and strong. Bergman uses his camera and actors for sharp, realistic effects.”

Tackling themes of great heft such as man’s mortality, spirituality, religion, and reflections therein, The Seventh Seal had a stunning visual symbolism that, as James Monaco describes it in his book “How To Read a Film” as being “immediately apprehensible to people trained in literary culture who were just beginning to discover the ‘art’ of film, and it quickly became a staple of high school and college literature courses… Unlike Hollywood ‘movies,’ [The Seventh Seal was] clearly aware of elite artistic culture and thus was readily appreciated by intellectual audiences.”