As the years go by, cars lose their curves, records lose their scratchy sound and homes lose their lace. Times change and so do we‒ all at one with our cultures, our aesthetics, our fashions. Change is a need. It’s an unstoppable force, maybe, but it doesn’t erase memory in its sweeping establishment.

On the detailed façade of an old building, in the faded pages of an old book and in the black-and-white frames of an old film we always seek the nostalgic reflection of a dusty past. Capturing all of the beauty and the wistful atmosphere of the 60s in France, “la Nouvelle Vague” carries an indestructible photograph of its truth.

Cinephiles love it, and so do artists and filmmakers. It has influenced the seventh art in an unlimited degree, as in relation to time and space so in relation to content and aesthetics. From the Danish Dogme 95 to New Hollywood, and from the idealistic revolution to the shooting innovation, the artistic impact of France’s iconic cinema of the 60s is catholically deep and essential.

Let’s stare at the beauty of the French New Wave through the films that mirror its visual style and character.

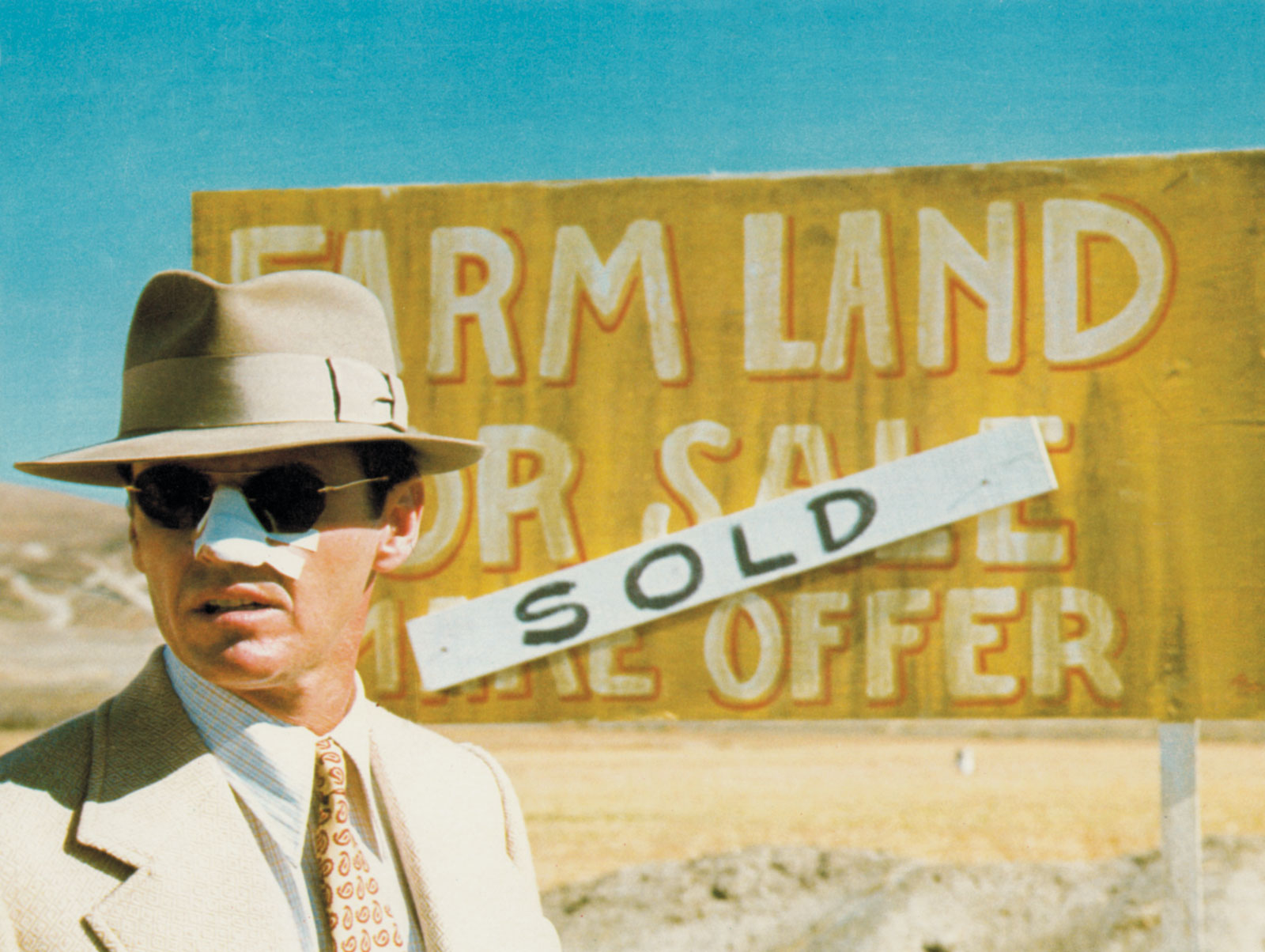

10. Chinatown (1974)

One of Roman Polanski’s best pictures and perhaps the most iconic neo-noir film, “Chinatown” definitely falls into a terrain of sad beauty and disguised corruption that François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard originally carved in a different soil. Set at the 1940s in America, it showcases a noteworthy authenticity of the era’s both charm and morbidity.

Polanski’s point of observation here is different than the one usually provided by the French New Wave auteurs, as they always follow the outlaw and he follows the external force that means to explore the shady waters of the story’s substance. In a more “American” style of narration and exposition, Chinatown reveals one of the most masterfully handled plot twist in cinema history, and still sustains a much more subtle ingredient of sorrow.

It involves a doleful, ultra-stylized woman. It contains guns, hats and officers. Of course, it’s quite known that the French New Wave has influenced the American crime cinema. But “Chinatown” lies on a silent desert of moral and emotional voids, in its effective and unforgettable beauty. Does its final shot remind you of something?

9. The Artist (2011)

French director Michel Hazanavicius has been charmed and inspired by Jean-Luc Godard’s work and political placement. It’s true that every artist has inspirational idols and Hazanavicius has extensively talked about his own, while he’s also filmed a picture about Godard, based on an Anne Wiazemsky’s novel that focuses on her experiences with the legendary director during their marriage.

His notorious, Oscar-winner “The Artist” goes back in the early silent era of Hollywood, attributing homage to its occurrence and fearlessly exposing its delirium. On its retro canvas we see the styles of the 30s. We see an America of dreams and reckless hopes. We see Charlie Chaplin, smiling somewhere behind a red curtain. Still, in its stunning frames and filmmaking artistic features we see France and the innovation brought by its old and eternal “Nouvelle Vague.”

“The Artist” is a self-indulgent, absolutely stunning and victorious trip through time and ambition. It doesn’t reveal the existential vanity and the fatal destruction of the French New Wave. However, it keeps the same undimmed love for filmmaking and filmmakers, as it sustains a glaring retro beauty which emerges in its dedication to the past.

8. Samson & Delilah (2009)

Perhaps music is the most easily spread form of art, instantly transcending cultures and sentiments all over the world. Cinema, in its audiovisual nature, fulfills this task all the same, proving that ideas and emotions are absolutely universal and timeless values. Australian director Warwick Thornton drops a glimpse of Europe and maintains a grain of universality in the raw beauty of his 2009 piece “Samson & Delilah.”

Landing on his territory, Thornton draws the lines of the existential meandering of two young, disoriented youths that search for an identity in the city, after leaving the countryside of the vast and chaotically diverse land that it is Australia. Escaping from the evasive cell that encloses a jungle-like community, the story’s hopeless Samson and Delilah are thrown in a relentless game of survival in a both bigger and harder societal jungle.

Obviously remote of France’s cinematic new wave, so in relation to time as in relation to space, “Samson & Delilah” as a piece of the seventh art simulates its shooting techniques and its revolutionary spirit. In the footsteps of a creature lost in eternity and in need of change, this film is a hidden gem that utilizes the beauty of the European cinema in a way quite genuine and otherworldly.

7. A Coffee in Berlin (2012)

The hipster film “A Coffee in Berlin,” in its tragicomic nightmare and pleasant simplicity, is a gorgeous picture that loves the French New Wave. Niko Fischer, the moonstruck university student that stars the film, isn’t chased by police or by a troubled past. Yet, he’s lost in a life of blurred edges and in a city of a both enchanting and demanding image.

Shot in black-and-white and captured in a high contrast, the stunning moving frame of this film follows the story of a boy and a city. In this case, the city isn’t Paris and Niko hasn’t a lot in common with Jean-Paul Belmondo, but he’s silently thoughtful, and his girlfriend has got the short haircut, the full lips and the stripped clothes of Michel’s Patricia.

In the witty, quite topical criticism that emerges in the 2012 “A Coffee in Berlin” you can’t see the pure drama that you see in almost every piece of the French New Wave. Still, in the streets of modern Berlin you can see the vintage streets of Paris, as you can see the swirling reflection of its chased heroes.

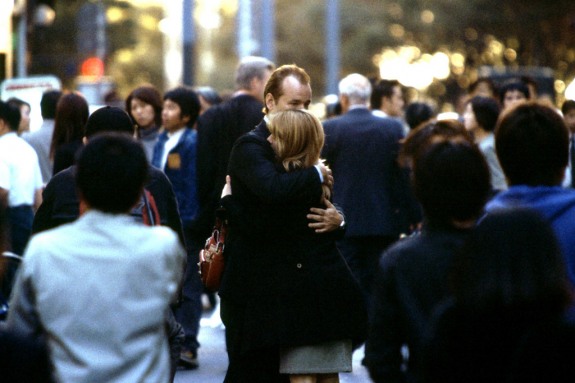

6. Lost in Translation (2003)

In the French New Wave’s idealistic territories, romance is always a tragedy. A man and a woman most of the times meet so as to unsettle each other‒ unwillingly but effectively. In Sofia Coppola’s iconic “Lost in Translation,” which essentially deals with matters as loneliness and repressed sentimentality, we approach a similar tragedy from a different point of view yet in a similar existential trap.

Moving slowly through time and following loose lines of narration, “Lost in Translation” is more about what isn’t said and isn’t exposed than about what it offers visually. The sadly lighted landscape of a culturally and linguistically distant Tokyo operates as a straying canvas that leaves the two heroes in a suspended loneliness which mocks their tensed yet utopian connection.

Despite its modern aesthetics and its even more modern concerns, this film describes quite complex characters and ideas in a welter of silences and in a subtle nonexistence of decompressions, as the auteurs of the French New Wave have repeatedly done. Here, Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson are two Americans in Asia, but they effortlessly carry the sadness of Jean-Paul Belmondo, Jeanne Moreau, Anna Karina, and of all the others…