The protocol which governed the selection of the following films is one that emanates from a particular conception of form and style. The films listed below take as their starting point not a conception of style as something superfluous, ornamental and subject to the caprices of the director.

The films below recognize that style is indispensable from cinematic production and from the interventionist nature of the medium. What animates these films is the idea of constantly being on the threshold of something new. They display a wide array of different registers of thought and a willingness to experiment with the cinematic apparatus while recognizing that cinema is the art of formalization par excellence.

On a further note, their stylistic experimentation refuses to reduce the viewer to a mere spectator and digester of spectacular and entertaining images. They engage and unsettle her. This is wherein their formal and stylistic subversive nature resides. These films can be filed under the category of visionary films, each in their own way opening new paths towards grasping the political condition of cinema and the subversive power of artistic formalization.

On the last instance then, these films are not anchored on the saturated conception of l’art pour l’art. They divorce from it in the very act of recognizing that cinema is a practice that reverberates in other practices, and is conditioned by other practices.

10. Arabian Nights: The Restless One (2015) – Miguel Gomes

Gomes takes off where he left with the work which first brought him to international prominence, Tabu (2012). If Tabu was an examination of colonial legacy, the political edge in Arabian Nights is further sharpened and directed towards illuminating the degradation of the concept of the political and the crushing power of bureaucratic decision making which has twisted politics into management.

Drawing from the structure of the famous One Thousand and One Nights tales, Gomes arranges a series of playful vignettes ruminating on the austerity measures and the economic crisis facing Portugal.

The film displays a plethora of approaches, ultimately sitting in a framework between fantasy and documentary. From a noisy rooster getting votes in elections, to a desperate and ailing swimming teacher trying to organize a new year’s therapeutic swimming session, Gomes sheds light on the absurdity of modern politics (or lack thereof).

The most memorable vignette is that of a group of impotent European Union bankers and local bureaucrats engaging in futile discussions and profiteering, before meeting a local man who will “cure” their dysfunction. Gomes has emerged as one of the most daring and idiosyncratic figures of 21st century cinema and the first volume of Arabian Nights is his strongest statement to date.

9. Videograms of a Revolution (1992) – Harun Farocki, Andrei Ujica

No introduction is needed for Harun Farocki. The remarkably talented director, heavily influenced by his masters Jean-Marie Straub and Danièlle Huillet, has year after year – from his denunciation of the Vietnam War in The Inextinguishable Fire to the often overlooked How to Live in the German Federal Republic – shown a great political consciousness and experimentation with the medium. Arguably, it is in his collaboration with Andrei Ujica that his inventiveness reached its peak in the examination of the dialectics of the image.

A mere three years after the fall of the Ceaușescu regime, Videograms of a Revolution is constructed from found footage- from amateur videos to footage of the state national television- and manages to chronicle the unfolding of a rebellion while using it as the backdrop to focus on the power of the camera apparatus, and the role of representation and vision in legitimizing political change. At one moment in the film, a group of protesters hysterically shout: We have won! The TV people are with us!

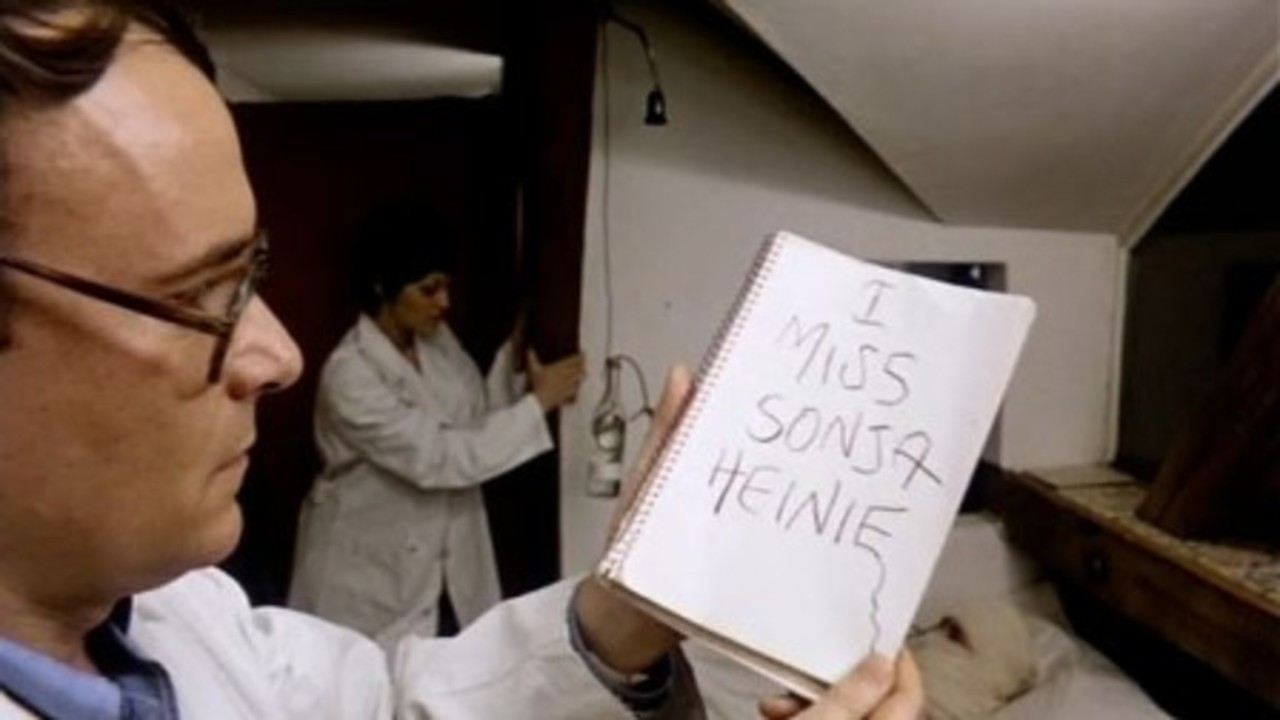

8. I Miss Sonia Henie (1971) – Omnibus film curated by Karpo Godina

One of the masters of Yugoslav cinematography and experimental film curates an almost Dadaist omnibus piece which includes contributions from Makavejev, Forman, Tinto Brass, Buck Henry, Paul Morissey, Frederick Wiseman and Karpo Godina himself.

A cinematic homologue to the lipogram experiments of the Oulipo group (Raymond Queneau and François Le Lionnais), the film is an attempt to work with restrictions wherein each of the short pieces curated here are subjected to the same limitations: same setting, camera fixed to one position, each film organized around the compulsory utterance of the sentence “I miss Sonja Henie”.

7. F for Fake (1973) – Orson Welles

Citizen Kane and The Trial have been heralded as Welles’ zenith in his cinematic career, but it is in F for Fake where the master is at his most innovative. It is Welles istic statement on the question of the work of art, its reproducibility, and the nature of authorship and representation. This colossal work has a stature somewhere between Batailles’ Death of the Author and Benjamin’s The Work of Art.

Welles employs his supreme talent for narration and story-telling to interpelate us in this fast paced, relentless juxtaposition of two rather eccentric characters: Elmyr de Hory, highly proficient art forger and Clifford Irving who authored a biography of Elmyr and is in turn a producer of hoax biographies.

Through tracking the dialectics and tensions between them, this is Welles’ most complete attempt at investigating what the specific site of film and cinema is, and thenceforth casting a retroactive look on his own work.

6. Can Dialectics Break Bricks? (1973) – Rene Vienet, Tu Kuang-Chi

Rene Vienet takes Tu Kuang Chi’s martial arts mainstream film (read: standardized cultural product) and renders it into a critique of capitalism. By means of what operation does he manage do this? By merely changing the dialogue of the film, while maintaining the original footage untouched. There is a name for this technique in the history of subversive artistic formalization: it is called détournement. It is a technique developed by the members of the Situationist International (Guy Debord being the most renowned), a group of heterodox Marxist theoreticians and avant-garde artists active especially during the May 68 strike.

Détournement amounts to carrying out interventions (usually minor) on mainstream cultural products (advertisements, films), such that it completely changes their meaning and original intent and undermines their destined role in serving as ideological mystifications in the reproduction of the relations of production. Vienet’s intervention turns this very “harmless” film into a rich investigation on the class struggle, alienation and the dynamics of the circulation of capital.