The name Tolstoy means many things to many people. Novelist, Aristocrat, Revolutionary, Heretic, and Saint are all titles given to the author of War and Peace – often considered the greatest novel of all time.

And it seems only fitting that someone capable of creating so many timeless fictional characters should have lived a richly complex life during which he embodied so many roles. But for now we will consider Leo Tolstoy the Philosopher – perhaps his most unexpected alias. His philosophy was the legacy that he cared most about, and its expansive scope and authoritative delivery deserve our attention.

Those with only a superficial knowledge of Tolstoy’s life may be intrigued by a deeper examination of his character. For instance, did you know that he was excommunicated by the Russian Orthodox Church for his uncompromising interpretation of the teachings of Jesus? Or that this very interpretation, which emphasized strict nonviolence, directly influenced Mahatma Gandhi? If you’re not aware that Tolstoy later referred to his own novel Anna Karenina as an “abomination that no longer exists for me,” then you’ll want to read on.

Studying films that reflect the philosophy of Tolstoy seems especially appropriate, for an artistic analysis of his beliefs helps to serve the spirit of the great artist himself. Of course he did not invent any of the beliefs he espoused, but the Russian writer applied his intimidating intellect to the issues he cared most about, and displayed the resulting knowledge in an exhaustive fashion.

Tolstoy’s celebrated writing skill, supported by a thoroughly informed historical perspective, make his philosophical works crucial reading for the curious mind. Here are ten films that focus on and further some of the ideas he cared most about.

1. First Reformed (2017) – Paul Schrader

First Reformed is haunted by the ghosts of so many classic films dealing with faith and spirituality that its importance as a modern statement on these subjects could be missed. But the main strength of its story lies in the timeless existential struggle which the film captures perfectly. The priest at the heart of the story is numbing his physical and emotional pain with alcohol, and has turned to the priesthood hoping to find spiritual answers and forgiveness.

Through harsh penance and austerity, he continues to seek an elusive peace with God and with himself. But when theological remedies fail to heal the cleric’s pain, his preoccupation transfers from spiritual salvation to social activism so easily that the two seem to be equated in essence. Meanwhile, his personal despair is growing into a threat to his very life from which even faith may fail to rescue him.

In 1882, a depressed and despairing middle-aged Tolstoy was nearing the end of his spiritual rope. With his prior belief system fraying into incoherent threads, the celebrated author demanded of life some existential answers. His search to find a life worth living and a truth worth believing yielded one of his first philosophical works, known today by the title A Confession.

In it, Tolstoy describes his own inquiry into the metaphysical questions which tormented his mind, and he shares his personal breakthrough into a spiritual awakening. This transformation opened the door to a fascinating second half of Tolstoy’s life, after his most famous novels were completed.

The answers he found which filled the void in his soul would become the foundation for all his future writing and living. Like the priest in the enigmatic final frames of First Reformed, Tolstoy had now stumbled into a mysterious new spiritual dimension.

2. Ikiru (1952) – Akira Kurosawa

“I can’t afford to hate people; I haven’t got that kind of time.” This is the attitude that the protagonist of Ikiru adops when he learns that he has only a few months left to live. After many years of mental and spiritual stagnation in his dreary office job, the sick man realizes that he has not truly lived for most of his life.

Determined to make a difference, no matter how small, in the world before he dies, he undertakes a community project with the gusto of a man with nothing to lose. The film’s study of his passionate final days, and of their influence after his death, presents an inspiration for the audience to embrace this brief life in a similar way. Fully grasping the brevity of life is likely to radically alter one’s consciousness, and Ikiru is a poignant example of one man’s response.

Though Kurosawa often turned to Dostoevsky for artistic inspiration, Ikiru is a loose retelling of a novella by Tolstoy titled The Death of Ivan Ilyich. Like A Confession, The Death of Ivan Ilych was written during a time of spiritual upheaval for the great Russian, and the book’s protagonist embodies the personal struggles of the author.

Both men reach a breaking point at which their old way of living is no longer an option, and both discover a spiritual rebirth after which they are determined to live their remaining days with passion.

Just as A Confession captures the existential crisis of a searching soul, The Death of Ivan Ilych seems to provide a blueprint for moving forward with one’s life – however much of it may remain. Thus begins an extraordinarily fruitful time for Leo Tolstoy during which he studied and wrote with a newfound zeal.

3. Au Hasard Balthazar (1966) – Robert Bresson

Director Robert Bresson made the unconventional choice to cast a donkey as his main character, and to follow its life from youth until death. By prioritizing the fate of this lowly protagonist, the film immediately lifts the animal’s intrinsic value onto a plane normally reserved for human characters.

Simultaneously, by considering a meek and passive creature, Bresson starkly highlights the intentional cruelty inflicted by humans on the beast Balthazar throughout his life. As Balthazar is passed from owner to owner he is the subject of many beatings, and his inability to defend himself seems to draw out the worst impulses in the people who dominate his life.

It’s a heartbreaking but enlightening saga that rings tragically true, and forces the viewer to weigh the ugliness of human behavior against that of the symbolically saintly Balthazar. The message of the film is all too clear, and it leaves a severe distaste for the societal norms which allow for cruelty to animals.

The cornerstone of Tolstoy’s philosophical structure was to be the principle – or, as he saw it, the commandment – to practice nonviolence. Drawing from Jesus’s instruction to “resist not evil,” Tolstoy applied the concept in the broadest way possible. Therefore, he firmly believed that nonviolence in its purest form would prevent the harming of all forms of life, including the animals commonly consumed for food.

It was to this end that in 1892 Tolstoy wrote The First Step: An Essay on the Morals of Diet, which positioned vegetarianism as a crucial decision which would help to turn people from the practice of cruelty. If one could apply the principle of nonviolence to even this extremity of its potential, Tolstoy argued that it would be almost impossible to willfully direct violence toward humans.

“If a man aspires towards a righteous life, his first act of abstinence is from injury to animals” he declared, and it was this attitude which made him one of history’s most influential proponents of vegetarianism.

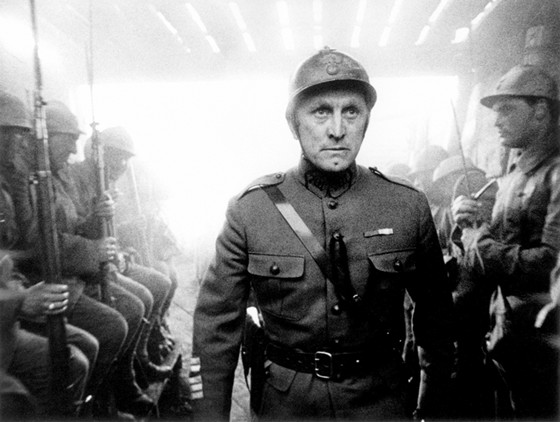

4. Paths of Glory (1957) – Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick’s brilliant film Paths of Glory is much more than just a World War I movie; it’s simultaneously a taut drama with enormous moral implications. Kirk Douglas plays a French Colonel who is given an impossible suicide mission for no other reason than that it will bring a promotion to the Colonel’s superior.

Refusing to lead the men under his command into certain death, he refuses to obey the orders. The upshot is that three of his soldiers are condemned to a court-martial and an almost guaranteed execution as a result. The Colonel’s ethical decision becomes a heavy weight around his neck, and the repercussions arising in its aftermath are carefully examined.

If a commander’s refusal to follow orders leads to the certain execution of some of his troops, is the commander still right to place his or her ideals ahead of the wellbeing of those who might be negatively affected by them?

In 1894, Tolstoy published his most important and influential work of philosophy, titled The Kingdom of God is Within You. A comprehensive manifesto of his beliefs, this book was banned in his home country of Russia, and was initially published in Germany. One of its central themes is the absolute immorality and absurdity of war, which Tolstoy viewed as little more than officially sanctioned murder.

The book finds an excellent companion in Paths of Glory, which remains one of the most effective anti-war films ever made. The obviously compromised moral position of the Colonel in the film is a dramatization of the viewpoint Tolstoy espoused in regard to war – namely, that a participant in battle would be completely unable to maintain one’s moral compass and make ethically honest choices.

Like the powerful world figures in War and Peace, the men of consequence in Kubrick’s film possess far less agency of free will than might be assumed; rather, by participating in war they find themselves swept up in the flood of larger events which act ruthlessly upon their sense of morality.

5. The Burmese Harp (1956) – Kon Ichikawa

After proving his bravery in battle, circumstances force our protagonist, Mizushima, apart from his unit. Narrowly escaping death, he takes up his beloved harp and begins the quest to rejoin his friends; but the death and destruction which line his path will change his life forever.

As Mizushima is confronted with corpse after corpse of once hopeful and promising young men, he feels compelled to give them proper burials. Losing himself in this higher purpose, he finds that the moral ideals he is embracing could keep him separated from his comrades and his home until his work is done.

We are asked to consider: do enlightenment and integrity require removing oneself, psychologically or physically, from the corruptive influences of a society? Some response is certainly called for by the principles which Mizushima is adopting, for true inner harmony should never be confused with outer conformity. Whether or not his choice leads to moments of social isolation is not an important question for this film.

The refusal to participate in violence and war is a decision which can only be reached with careful consideration. In The Kingdom of God is Within You, Tolstoy masterfully presents myriad examples of individuals and groups of people, such as the Quakers, who consciously chose to practice nonviolence.

He also carefully details the reasons why they made such a radical decision, and offers powerful arguments against the corruption that he saw in human culture. For the protagonist of The Burmese Harp, the wakeup call was a direct observation of the atrocities of war which he witnessed in the decaying corpses of young men who might have lived full lives.

For Mizushima and for Tolstoy, such honest acknowledgements of a violent society demanded a new approach to life: if violence begets more violence, then firm action must be taken to stem the tide. Reading The Kingdom of God is Within You is akin to taking a stroll through the graveyard of history, and it’s an experience not easily shaken off.