It’s always nice to remind oneself of those films that try and innovate – the independent, the experimental – those that take an unusual or distinctive glimpse at the world, or the films that just try something a little different.

Orson Welles’s ground-breaking Citizen Kane (1941) reminded Hollywood that one man could make storytelling clever and inventive. Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali’s combined effort Un Chien Andalou (1927) was a keystone in surrealist filmmaking. George Melies experimented with new editing and set design techniques to make cinematic magic tricks; Sergei Eisenstein adapted editing to form symbolic montage, witnessed most famously in Battleship Potemkin (1925). The Italian Neorealists provided a crude cinema as a comment on the harsh post-War Italian landscape, whereas the French New Wave pioneered a self-aware, iconoclastic filmmaking style as a rejection of traditional filmmaking conventions, adding a fresh, original edge to their work.

Auteurs like Andrei Tarkovsky and Bela Tarr offered us slow, meandering meditations on existence, time, and place. David Lynch burst onto the scene with surreal, dreamlike critiques of Hollywood and modernity. Documentary directors such as D.A. Pennebaker or the Maysles brothers brought new non-fiction styles through a handheld, independent observational etiquette. Ingmar Bergman gave us philosophical meditations on the human condition. And Wong Kar-wai continues to bring striking images to film-goers by experimenting with bold colouring.

‘Arthouse’ or ‘avant-garde’ are terms difficult to whittle down and define; the ramble above suggests that the art film takes many forms and styles by varying techniques. Though what is evident of the art film is its indisputable importance in film history, contributing towards beautiful, daring, and stimulating cinema.

10. The Dance of Reality (2013, Alejandro Jodorowsky)

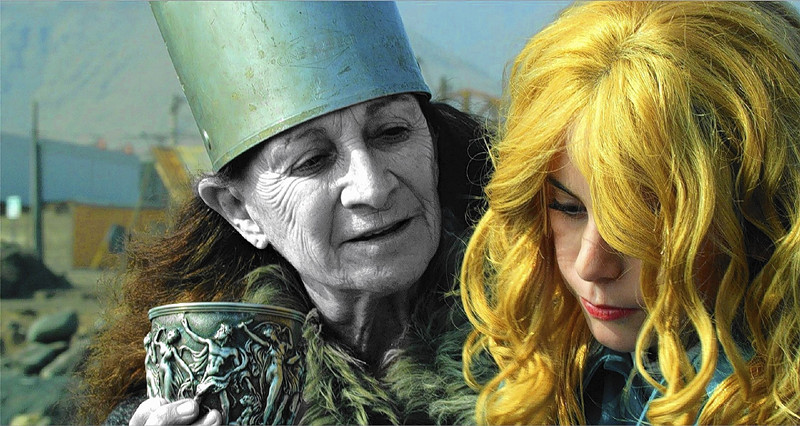

The Dance of Reality (2013) was Alejandro Jodorowsky’s first film in 23 years. An autobiographical work, the film depicts a young Jodorowsky (Jeremias Herskovits) as he navigates childhood monitored by an abusive, prideful atheistic father (played by Jodorowsky’s son, Brontis)—once a circus strongman, now a Stalin-idolising Communist. Young Jodorowsky is helped by the prudence of Jodorowsky himself, who acts as an occasional ghost of Jodorowsky’s future, guiding the young man away from suicide.

Filmed and set mostly in Jodorowsky’s actual hometown of Tocopilla, the film is littered with magical and memorable images. From the vibrant colouring of the houses—reminiscent of the work of Pedro Almodovar—to the hundreds of birds flocking over a beach full of dead sardines, or a half naked Theosophist (Axel Jodorowsky), Jodorowsky meanders the fantasy of the past: things are exaggerated, made up, or altered. Crucially, his mother—who speaks through operatic song—teaches the young Jodorowsky about God, about facing the dark, and about not fearing the anti-Semitism he and his family are—sometimes violently— confronted with.

It is a bright and beautiful film packed with song, comedy, and a host of wild, surreal characters. One of these many side characters, many of whom are characterised by harsh disabilities symbolising a widespread misery, comments that ‘nobody can escape their destiny.’ By the end of the film, Jodorowsky drifts off alongside a skeleton; perhaps he has found a way through his art to reconcile his past with his destiny.

9. Funeral Parade of Roses (1969, Toshio Matsumoto)

Funeral Parade of Roses (1969), directed by visionary Toshio Matsumoto, is a film way ahead of its time and should be considered a landmark in LGBTQ+ cinema.

A product of the Japanese New Wave, Funeral Parade is a loose adaptation of Greek tragedy Oedipus Rex and tackles the taboo subject of Tokyo’s underground gay culture. In following transsexual Eddie (played by Pîtâ, recognisable for his role in Akira Kurosawa’s Ran [1985]) we are led through a world in which he struggles with his identity while he and his lover Jimi (Yoshimo Jô) continuously try and avoid the jealous Leda (Osamu Ogasawara), the head transsexual at a gay nightclub.

Inspired by the work of the French New Wave, Funeral Parade of Roses is a combination of various devices: chopped up music, vividly brutal flashback sequences, harsh jump cuts, brightly lit sex scenes, montage, and random cue cards that flash on screen with unjustified exclamations. Even the title flashes 20 minutes in, a brief but insouciant reminder that we are watching a film.

The film’s most effective device, though, is its use of documentary-style interviews. ‘Do you like men?’ is answered with ‘yes… no… I like gays.’ ‘Do you not see women as sexual objects?’ ‘It really depends; there are many types of gays.’ The effect is a blurring of fact and fiction to place poignant, progressive points of discussion at the heart of the narrative—it’s easy to forget that this film was made in the late 60s.

Funeral Parade of Roses makes the outsider (which coincidentally seems to be a running theme throughout this list) the protagonist. An important watch.

8. A Hidden Life (2019, Terence Malick)

A Hidden Life (2019) continues Terence Malick’s style of filmmaking widely panned in his recent few efforts; critics have declared it washy, plodding, and unspecific. Here, however, Malick places his swooping cinematography and grandiose aesthetic into the context of World War Two, to great and successful effect.

Based on the true story of conscientious Austrian objector, Franz Jägerstätter, A Hidden Life mirrors his internal conflict through Malick’s free-flowing camerawork to reinforce ideas of struggle and displacement. This motion can turn quickly wide-shots of vast landscapes into extreme close-ups, making it an effectively delirious watch which is in turn capable of displacing its viewer in a way. This dreaminess was generally considered aimless and dizzying in his most recent films, but in this case it is grounded beautifully in the mud and dirt of Franz’s rural homeland and the struggle he encounters when captured by the Nazis.

A Hidden Life is not Malick’s best film, but it does see him firing right back on form.

7. 24 Frames (2017, Abbas Kiarostami)

“I always wonder to what extent the artist aims to depict the reality of a scene. Painters capture only one frame of reality and nothing before or after it.” – Abbas Kiarostami.

Abbas Kiarostami’s final film 24 Frames (2017) is an undeniably experimental work that abridges the still and moving image. Kiarostami has melded his dual loves for filmmaking and photography by structuring this work around a set of 24 different paintings or photographs, referred to as ‘frames’, digitally editing them to allow insight into what happened before and what follows. A magical mix of landscape pictures, snowy scenes filled with cows and crows, and monochrome images of windows, he displays and builds story through cleverly layered editing.

With each frame edited to make roughly four and half minutes of action, Kiarostami truly challenges our patience. Each one immerses us into its environment and mood, forced to dwell in its confinement. As we notice the harshness of its snow, then the sound of its wind, then the many more intricacies of its beautiful landscape, the rewards of taking time out to observe our world are highlighted to us.

24 Frames is a film that takes cinema back to its roots and celebrates the single, moving image. It is an experiment Kiarostami takes his time with, trusting in the significance and beauty of the photographed moment.

6. Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988, Terence Davies)

Perhaps often overshadowed by the politically-charged films of Ken Loach, or the emphatic naturalism of Mike Leigh, the tender and poetic work of Terence Davies transfigures the kitchen sink realism most associated with British cinema into new, beautiful experiences.

Unlike Loach who explores social injustice and the effects of external forces on the working class, Davies in Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988) intimately explores how internal forces— family, home, community, the pub—keep them afloat. As such, Davies’s films are more hopeful; their characters are collectively expressive and emotional. This is often expressed lyrically as the characters are regularly found singing, either in a moment of communal joy or one of pain, in a pub or in an air raid shelter.

In a film of distinct halves, the first, ‘Distant Voices’, is a memory of a father (portrayed with a firmness and severity by Pete Pothlethwaite). Its frames often begin in stillness, like photographs, before being interrupted by an abrupt act of violence. The main ‘movement’ is initiated by the music that seamlessly bridges different moments and times; Davies uses a song or hymn as a reason to pan around a room or slowly drift from one location to another.

Loosely inspired by Davies’ own life, the film meditates on the importance of family and memory whereby the three central siblings remember their father through different perspectives. In ‘Still Lives’, song gives respite to hard times, and is a binding force between the characters, giving the community a unique voice beyond their usual working class lives.