What is it that makes a film “weird”? Really, the term “weird film” is one that’s thrown around almost every day, and could mean many different things to many different. It could refer to anything from a film that simply evokes some trippy imagery or plays around with the conventions of its genre, to a film that completely defies the conventions of cinematic narrative and inspires us to question our very understanding of what a movie can and should be.

Whatever your notion of a “weird film” might happen to be, though, the fact is that, in amidst all the samey cinema out there, there’s also a great amount of strange, surreal, absurd, confounding, and downright weird movies that have slipped under the radar. After all, weird movies, by their very nature, tend to have a very niche audience; and if they’re not marketed to that audience properly, they run a serious risk of simply not being seen at all.

So below, we’ve listed ten strange pieces of cinema that even the weirdness aficionados out there might not yet have come across.

1. Shakespeare’s Plan 12 From Outer Space (1991)

This is an especially befuddling one. There’s virtually no information about it out there, and the director, Charles Montgomery “Spike” Stewart, seemingly directed nothing else besides a documentary about the LA music scene.

Either way, you can probably tell from the title just what a crazy ride this one is. Ostensibly, it’s an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, and indeed, it follows the original text pretty closely. There’ve been plenty of examples of the Bard on film that take more creative approaches (usually by transplanting the action into a contemporary setting, or utilising unusual costuming and props); however, none of them come close to this psychedelic 90s spin on Shakespeare’s classic romantic comedy. The film was partially shot on a children’s video camera, and the often grainy, low-quality picture is played over a background of sprawling night skies – intended to evoke, apparently, that this version of Illyria (D’Ilyria, as it’s called) is a space station on some distant planet.

Then there’s the constant quotations from other Shakespeare texts that flash onscreen, the deliberate attempt to evoke Ed Wood’s editing style…really, the list of absurdities could go on forever. It’s the kind of thing that you really have to experience for yourself. Just keep in mind, this is the kind of film that’s deeply weird in a very deliberate way – you’ll need to be willing to pay attention, and be well-versed in the original text, to understand what’s going on for even a moment.

2. Motivational Growth (2013)

Gamers out there might be surprised to learn that Devolver Digital, best known for publishing indie games like Hotline Miami and Enter the Gungeon, also has a film distribution department. Sadly, they don’t seem to have done much in recent years; but one of their 2013 outings, Don Thacker’s Motivational Growth, exudes modern indie weirdness all the way through.

We follow Ian, a severely depressed man living in a squalorous apartment he hasn’t left in months. This does, admittedly, sound like a rather dark setup; but once Ian hits his head during a failed suicide attempt, and a lump of mould in his bathroom starts giving him life-coaching advice in the voice of Jeffrey Combs, things get considerably more light-hearted.

Motivational Growth is replete with that offbeat, quirky tone that came to define indie cinema over the last two decades. There is, perhaps, room to argue that it doesn’t tackle the topic of depression quite as delicately as it should; but there’s no denying that it builds on a unique premise in a unique way. The film takes place in some absurd world where everyone – from the repairman who diagnoses broken TVs by licking them, to the landlord who seems more focused on impressing his incarcerated brother than collecting full rent – seems at least a little bit insane; and the viewer is made to feel as if they’re sharing in Ian’s growing mental instability by way of weird hallucinatory sequences. It’s a film that really stands out as the better sort of weird indie effort – the kind that isn’t scared to push the boundaries of genre convention for the sake of it.

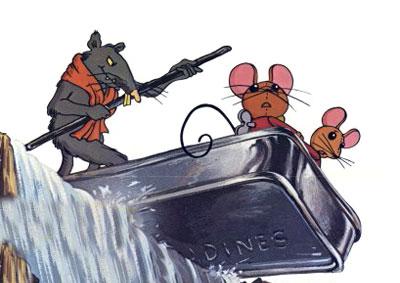

3. The Mouse and His Child (1977)

Don’t be fooled by the cutesy art or the seemingly child-friendly premise; The Mouse and His Child might just be the most philosophical and introspective film in the history of Western animation. We follow a pair of clockwork mice – a father and his son – as they are accidentally swept out of the toyshop. Lost out in the cold and snowy wilderness, they set out on a journey to become “self-winding”.

Along the way, they encounter what might be described as the standard cast of a children’s movie after they all hit middle age, began questioning their direction in life, and started reading a whole lot of philosophy books. There’s a frog who’s struggling to make peace between his fake fortune-telling business and his sincere belief in the concept of destiny. There’s a tech-savvy shrew who lives beside a pond, so constantly focused on abstract mechanical concepts that he seems to have forgotten that his talents have practical applications. And perhaps most memorably, there’s an ancient turtle living in a lake who has developed an obsession with the Droste image on a can of discarded dog food – he’s convinced that there’s some great cosmic truth at the end of it.

It’s not often that an animated movie about a pair of lost clockwork toys makes you contemplate such things as the search for infinity, or that universal human drive to claim true personal freedom; but The Mouse and His Child will do just that. The combination of a children’s movie’s aesthetic with the kind of introspective, abstract subject matter that even most adult films tend to consider a bit too high-brow is surreal and disorienting; but it’s an experience that you’ll be stewing over long after the film ends.

4. Ticket of No Return (1979)

Ticket of No Return (or Bildnis einer Trinkerin, to give it its original title) recently received some much-overdue international attention when it was screened during the We Are One online film festival; but it’s still a greatly under-appreciated film, and its director, established German filmmaker Ulrike Ottinger, remains criminally under-recognised in the English-speaking world.

The film’s narrative follows an unnamed woman (credited simply as “She”) as she travels on a one-way ticket from France to West Berlin, where she intends to indulge in her one passion: alcohol. The woman travels her way across Berlin, getting hammered at every high-class restaurant and café, every seedy pub and cosy hotel room she comes across. She never utters a word, and we never learn anything about her, or what drove her to this state of absolute obsession with drinking; the film, it becomes clear, is not about her, but about alcohol in general.

Along the way, the woman’s actions are commented on by three other women, appropriately named Accurate Statistics, Common Sense, and Social Questions. These women serve as something of a Greek chorus to the story, each one offering her own input on the issue of alcohol, its impact on society, and the way it is marketed to the world. All this is undercut by a thought-provoking theme regarding how, especially at the time, certain public behaviours seen as normal in men were considered scandalous when indulged in by women.

And yet, despite centring entirely around the grim topic of alcoholic addiction, the film never feels grim or depressing. In fact, it’s often tremendously lighthearted; the loosely-connected narrative has the voiceless protagonist doing everything from tightrope walking while drunk, to crashing a dinner party and helping herself to several spoonfuls of sauerkraut.

There’s countless films about alcohol out there; but you’re unlikely to ever see another quite like this one. Located at some strange midpoint between comedy, arthouse, and social commentary, you’ll likely have an entirely new perspective on the impact of alcohol, as well as the notion of cinematic narrative, by the time it’s done.

5. Alice in Wonderland (1966)

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is, of course, one of the most universally beloved children’s books out there, and there have been countless efforts to bring it to the screen over the last century. And while many of them are excellent, and quite a few of them are weird (since, you know, the source material is pretty weird itself), there’s none quite like this minimalistic teleplay made by Jonathan Miller for the BBC in 1966.

The first thing you’ll notice is that there’s no anthropomorphic characters in this one – no rabbits or dormice or playing cards. Instead, the entire cast are ordinary humans in Victorian costumes. The next thing you’ll notice is that the tone is quite unlike any other Alice adaptation. It sticks closely to the text of the book, but it’s slow, and sombre, and even quite frightening at times. These stiff-necked ladies and gentlemen deliver Carroll’s whimsical dialogue in dreary, deadpan monotones, creating a strange disparity that makes this version of Wonderland somehow feel even more unreal by way of being more mundane.

Miller stated in an interview that his intention was to evoke what he believed to be the central theme of Carroll’s books: the confusing world of adults, as seen from the eyes of a young child. In stripping away the animal characters, we’re left with a cast of adults bumbling their way through a succession of absurd rituals and conversations as we, and Alice, look on, silently pondering whether this collective madness really is what defines the experience of being grown up.

1966’s Alice in Wonderland is probably one of the most understated examples of “weird” cinema, with its dignified and understated Victorian sensibilities. Nevertheless, for those who consider the Alice stories to be a quintessential part of their childhood are likely to be struck by the unique spin that Miller’s adaptation gives to this classic. Though strangely cold and muted, and frightening in the quietest sort of way, it inspires introspections on the deeper themes of Carroll’s amusing tale of nonsense that few other adaptations can bring about.