Something was happening to the western in the 1960s and ’70s. The old screen heroes were ageing out and so were their moralities. The Shootist (1976) saw John Wayne confronting his age and mortality, while Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971) and Peckinpah’s Pat Garett and Billy the Kid (1973) cast the western’s classical heroism into an elegiac doubt. This was what came to be known as the revisionist western, a wave of westerns demythologizing, mourning, and critiquing John Ford’s west of good guys in white, bad guys in black, cowboys and Indians. Meanwhile from out of Italy came the so-called, spaghetti westerns, notably those of Sergios Corbucci and Leone, themselves already a kind of cynical deconstruction of the traditional western which replaced morality with greed and heroism with brutality.

But then there was another strain of western forming, frequently critical of the genre conventions but less interested in declaring the death of the western than revitalizing it and using its popular mythography to new and experimental ends in surrealist filmmaking. This was the “acid western” as Jonathan Rosenbaum would finally term it in his 1995 review of Dead Man, and marked the psychedelicization of America’s much-loved genre introducing it to the realms of the spiritual, metaphysical, and abstract, outside the historical setting traditionally essential to the genre.

The introduction of the conventions (or anti-conventions) from throughout the surrealist tradition, the psychoanalytic dreamstuff of Maya Deren’s At Land (1944) and Meshes of the Afternoon (1944), the absurdist allegory of Bunuel’s Simone of the Desert (1965) or Arrabal’s I Will Walk Like a Crazy Horse (1973), the counterculture picaresque of Jodorowsky’s Fando y Lis (1968) or James Broughton’s Dreamwood (1972), and the archetypal minimalism of Philippe Garrel’s The Inner Scar (1972) or Alain Robbe-Grillet’s Eden and After (1970). At its best, the transformation of the western gunslinger’s wandering into a spiritual kind of seeking.

And what better place for an American surrealism than the desert plain, the untamed frontier, a dangerous and spiritual land, the great empty expanse, under stars, home of the mescaline yielding peyote plant, source of thousands of years of sacred knowledge. And what better figure to descend down into an American unconscious than the man with no name? The lone wandering gunman?

So here are 10 films that bring the world of dreams to the wild west.

1. Dead Man (1995)

Jim Jarmusch’s 1995 Dead Man is the western as a katabasis, the spiritual journey of a mortally wounded man passing from the realm of the living into the dead. The man is William Blake (Johnny Depp), a mild-mannered accountant – apparently unaware of his English-poet namesake – who has taken a train to the end of the line, to the industrial mills of Machine, USA for a job he finds no longer open on arrival.

After getting himself shot the first night in town – wrong place, wrong time – and killing his assailant in turn, he takes to the hills where he is met by a native man named Nobody (Gary Farmer), a great admirer of the poet William Blake who becomes for Depp’s Blake a kind of underworld guide. He insists he is a reincarnation of the poet and encourages a recalling of his past life. Pursued by lawmen and bounty hunters, Nobody and Blake flee through the woods to a Makah village where Blake is to be cast-off in a canoe to make his final passage.

The film follows Blake’s pursuit, hallucinatory visions, and transformations toward death. Shot in an ethereal black and white by the master Robby Müller, it is a film full of mystic imagery, and surreal, grotesque exaggerations of old west mythology. It quotes heavily from Blake, not only in recitations of his verse but in a screenplay that draws itself heavily enough from the poet’s work for Jarmusch to have called him a co-author from beyond the grave. Elsewhere the film draws heavily on Native American culture – with untranslated Cree and Blackfoot speech – and allusive of American poetry and ancient Greek myth.

The film most of all takes its character from a score by Neil Young, which is, in its muddy distorted improvisation, less a traditional soundtrack than a running commentary of guitar accents that react to the action unfolding on screen, sonically interpreting and narrating the events of the film as it played to Young.

2. The Shooting (1966)

The Shooting is a western from director Monte Hellman shot in 1966 under advice of Roger Corman back to back in with the more conventional Ride in the Whirlwind using much of the same cast and crew, allowing Hellman to take a risk on Carole Eastman’s surrealistic screenplay (written under “Adrien Joyce”) within the production of a saleable b-western.

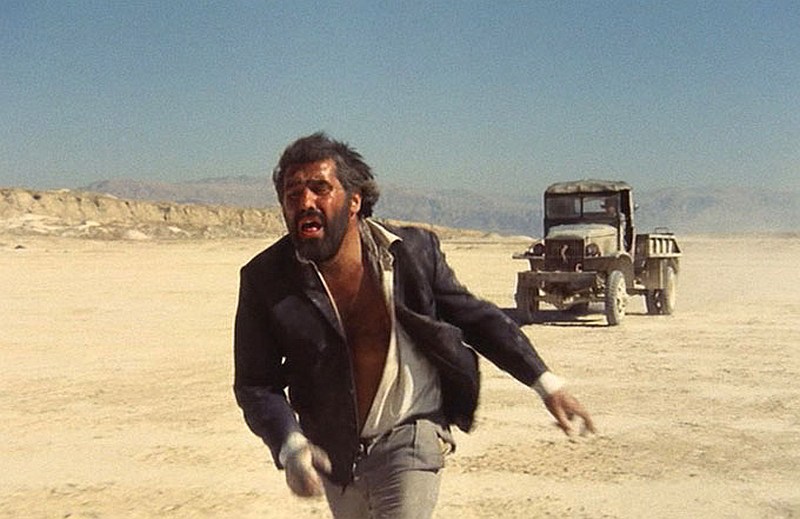

The film follows Willet Gashade (Warren Oates), a miner with a dubious past, and his reluctant employment by a wealthy woman-in-black (Millie Perkins) as an escort across the desert to the distant town of Kingsley. Joining the two is Gashade’s dim-witted companion Coley (Will Hutchins), the last remaining member of his mining camp after the disappearance of Gashade’s twin brother Coigne and the mysterious murder of their companion L.D. by an unseen assailant, and later by Billy Spear, Jack Nicholson’s vicious man-in-black counterpart and a hired gun of Perkins’, whose introduction makes the escort party into something of a hostage situation.

Gashade knows the escort will end in murder, only he can’t be sure of whose, or why. As the party advances, they begin to run out of water and have to shed extra gear when the horses grow weak and close to death. It seems they are going to fry out there, but Perkins and Nicholson seem unconcerned, driven by some higher law or inarticulable purpose.

Opaque and ambiguous, riddled with questions of sanity, reality, and reason, The Shooting is quietly metaphysical in the best kind of way – often compared to Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot – the film seems to occupy that same strange edge-of-reality space.

3. Deadlock (1970)

Deadlock is a 1970 western from director Roland Klick and – probably the only of its kind – a krautrock western, scored by legendary German psych-rockers Can. In the spaghetti western tradition Deadlock is a white-knuckle standoff between three amoral vultures over a briefcase of stolen cash. Unlike Leone’s westerns, which insert the mythic figure of Eastwood’s man with no name into historical reality – between feuding families, between union and confederacy – Deadlock is set in a weirdo end-of-time ghost town nowhere where one wonders what these characters even want the money for.

The three-way standoff is between two robbers and backstabbing partners in crime ‘the kid’ (Marquard Bohm) and ‘Mr. Sunshine’ (Anthony Dawson), and a local miner (Mario Adorft), who as the town’s only resident beside his wife and a mute feral girl (Mascha Rabben) is also its self-appointed law. There is no motivation beyond simple greed. It is a distillation of the spaghetti western to free-floating archetypes, almost to parable.

Following the spaghetti western tradition the film relies heavily on its soundscape to build tension, an exaggerated foley against the empty arid desert (as in the wordless opening of Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)) but takes it further into a kind of synesthetic musicality which melds with hallucinatory imagery – the sound of a creaking of a sign translates in the kids’ minds’ eye to the rhythmic rocking of a boat – and the building of Can’s score from a slow and wide trance state to the explosive Bruce Conner montage freakouts of sun and guns and screaming when the film goes off.

4. Walker (1987)

Alex Cox’s 1987 Walker is the true story of American filibuster William Walker who staged a takeover of Nicaragua in the 1850s on behalf of a rail tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt under the guise of democratic liberation ideals. Cox uses the filmic convention of the western to satirically frame Walker’s story, which portrays him (Ed Harris) as an ironic lawman hero (think Verhoeven’s lampooning of propaganda films with the ironic fascist-optimism of Starship Troopers) and parallels Walker to the cowboy president Ronald Regan who began his career gunning down natives on the silver screen and was responsible for US involvement in Nicaragua’s contra wars.

The allegory is not subtle, Walker’s men are mercenaries and Nicaraguan ‘liberals’ essentially owned by foreign railroads reflecting the not-so-grassroots nature of the contra groups the US employed to fight Sandinista (around the same time as they were funnelling money to what would become the Taliban) and as the film goes on Walker’s reality is made to bleed right into the 1980s with more and more refuse from the future showing up in the past, Marolboros and Coca-Colas, M16s, and sportscars, climaxing with the appearance of a state department helicopter dropping a bunch of CIA men into the city of Granada.

It is a surreal convergence of timelines that suggests the repetition and interconnection of history, the story of Nicaragua 185X, of Nicaragua 198X – of the whole history of Western imperialism – from an era which itself declared liberal democracy triumphant over the political process and history at its end. The agitation on display did not go unnoticed. The film, distributed by Universal but shot in Nicaragua with a largely Nicaraguan cast and crew, essentially ended Cox’s career as a viable mainstream filmmaker.

With a jaunty adventure movie score by Joe Strummer Walker is a blackly funny movie, contrasting the noble speechifying of William Walker’s empty ideals with the blatant pillaging and exploitation which follows in its wake, and a surreal repurposing of the western genre which seeks to call the iconography of the entire genre into question.

5. The Last Movie (1971)

The Last Movie (1971) is probably best known as a failure for actor-director Dennis Hopper, who coming off the massive success of Easy Rider (1969) and feeling not a little messianic – Jesus Christ and Jean-Luc Godard rolled into one – essentially tanked himself with this overambitious mess and monetary disaster. But today The Last Movie stands up as a radical meta-perspective on the western genre and in many ways seems to presage Heart of Darkness films like Apocalypse Now (1979) and Fitzcarraldo (1982), and even predict the metafictional interest the production of these films would garner, with critics calling their re-enactments of war-party/colonial enterprises a kind of restaging.

The film follows Hopper as stunt actor Kansas, on a Hollywood western shot in rural Peru and explores an intermingling of the western within the western – full of hyper-violent Peckinpahesque shootouts – and chaotic behind the camera footage of its production, which is in its own way also a self-reflection of The Last Movie’s own production. The film plays with a precarious reality from the get-go, the audience never sure which reality they’re in when cutting to a new scene, as many of the scenes of the cast and crew still costumed hanging out around the movie sets are indistinguishable from the in-movie scenes of the same, and in one scene reminding of David Lynch’s Inland Empire, Kansas comes in from the countryside on horseback riding right into the middle of a live set apparently unable himself to distinguish the reality from fiction.

But the real trouble begins when the film wraps, the production up and leaves, save for Kansas and a few other stragglers, to find that they have inadvertently created a cult among a group of natives with no understanding of film who begin re-enacting the stunt-violence they observed for real, before effigy cameras and audio equipment, calling ‘action’ and ‘cut’ either side of real ritual violence. And soon, Kansas, an artifact of the original production becomes a sacrificial figure for the cult and is sentenced to death, held in the movie’s leftover set prison.

The film is not without faults, its detractors not without a point. The Last Movie feels like the product of exactly the kind of frenzied production it portrays – playing out kind of slapdash without a good sense of coherence or structure, too many characters to keep track of, and many scenes and subplots arising to go nowhere, but in this there is too an unstable energy hanging in the balance between madness and profundity. If nothing else The Last Movie is a terrific monument to a particular era of Hollywood and a uniquely American insanity – a bunch of hippies getting loaded and losing their mind playing cowboy in someone else’s country.