Cinema is one of the most direct forms of expression artistic voices have. Films are most often incredibly human and personal, allowing for glimpses into the lives of the characters a director/writer has created which in turn allows for a glimpse into the psyche and culture of the creators. Since this connection between creator and viewer is often so clear, cinema is also a fascinating way to understand other cultures.

There is so much to be learned from world cinema, no matter what country you call home. Chinese films feel different than French films that feel different than Japanese films that feel different than Italian films that feel different than Korean films. Though there are certainly some very well-known heavy hitters of world cinema, it is also important to look at some of the ones that slipped through the cracks. These films represent a fairly even spread of the world and of the century long history of this artform. Here are ten forgotten masterpieces of world cinema.

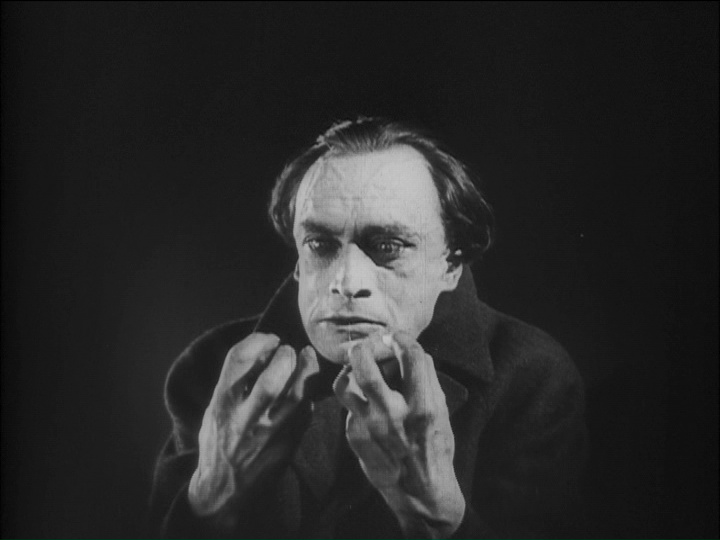

10. The Hands of Orlac (1924)

The legendary director of this film, Robert Wiene, has an extremely important place in the history of cinema. One of the founders of the German Expressionist movement in the 1920s, which produced classics like his own Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu, the tale that popularized the classic vampire from Transylvania that is now a household name. This movement also serves as a sort of birthplace for the horror genre, including the aforementioned classics as well as the 1924 classic, The Hands of Orlac.

The film is about a famous and talented concert pianist named Paul Orlac. Orlac suffers a terrible accident, and he loses his hands. His wife tries to get the doctor to save his hands, as they are his life and livelihood. Though his true hands could not be saved, the doctor solves the problem by grafting the hands of a recently executed murderer onto Orlac’s arms. Once the reality of those hands sets in, Paul becomes maddened by them. He can no longer play the piano, and every dangerous object puts him into a rage, a desire to kill. Complete with the traditional motives and tropes of the Expressionist movement while also having a more contained and coherent visual style, this film is a wildly important statement that furthered the canon of cinema.

9. The Blood of a Poet (1932)

The Blood of a Poet is another very old film by another legendary director. Jean Cocteau was many things to the world and to the country and culture of France: filmmaker, poet, playwright, designer, critic, impresario, benefactor, and visionary. By far his most notable contribution to film was his Orphic Trilogy, for which The Blood of a Poet serves as the first installment.

This film follows a poet and artist through a series of poetically linked events, each as profound as the last. The poet creates a sketch whose mouth begins to talk to him. When he tries to wipe it off, the mouth appears on his hand. He then puts the mouth on a statue, who talks to him. Through some stunning visual effects, the poet then travels through a mirror and ends up at a hotel, where he sees certain things happen, each unique and yet still related to one another. The final sequence of the film builds towards a fantastically bizarre climax that is quite striking and quite memorable. This is a film everyone should see a few times in their life.

8. Story of a Prostitute (1965)

The first Asian installment of the list, this film by Seijun Suzuki doesn’t get nearly enough attention. Like all great films, it is about many things: love, death, tragedy, war, humanity, and pain. It shows the many dimensions of the Japanese psyche while maintaining a generally minimal tone both visually and aurally.

Story of a Prostitute is about a woman who volunteers to be a “comfort woman” on the Manchurian front. The volunteer numbers were very small, so only a handful of women were responsible for servicing hundreds of soldiers on the front. A sensitive man, Mikami, enters her room, who the main character takes to. His demeanor and treatment of her was unlike any she had received before, and she took notice. They were soon interrupted by Mikami’s superior, Lieutenant Narita. Through the eyes of our comfort woman, Suzuki shows us the wide array of human expression and human treatment while providing an interesting critique on the ideas of honor that are so innate in his culture.

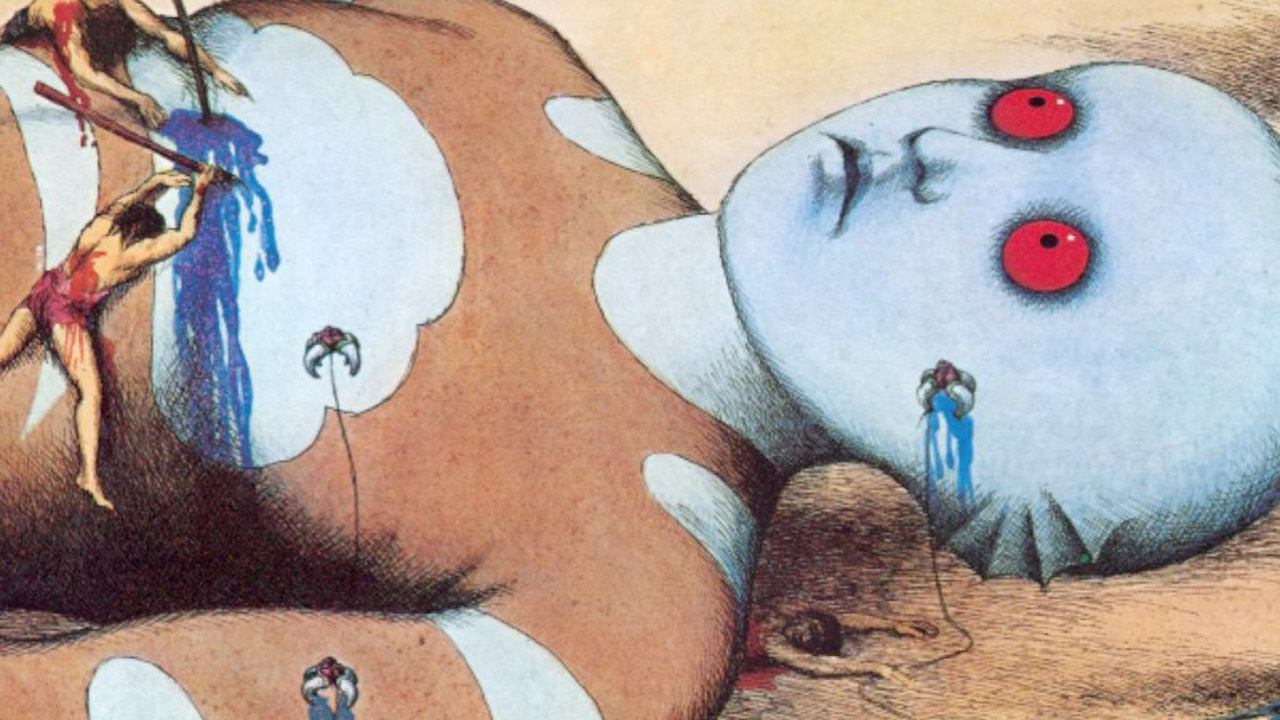

7. Fantastic Planet (1973)

Another French film, this wonderful piece of cinema certainly stands out in style from the rest. It is the only animated film on the list. The director, René Laloux, began to dabble in animation in the 1960s when he was working at a psychiatric institution. He made his first film there, entitled Monkey’s Teeth, with the collaborator Paul Grimault, and later made Dead Times and The Snails with Roland Topor. With a potent combination of humor and political commentary, Laloux developed an immediately identifiable voice that permeates through all his work.

Fantastic Planet is certainly Laloux’s most known work. It is the fascinating tale of an alien planet that has two distinct species: the Draags and the Oms. The Draags are the ruling race; humanoid in form but blue in color, and the Oms are the oppressed race. The Oms are entirely human in their presentation. The better treated Oms are like pets, they are observed and occasionally played with. The less fortunate Oms are hunted and murdered as toys by the Draags. When one of the Oms accidentally receives a sort of education from a Draag, the Oms begin to unify and rebel against the Draags. A multi-layered commentary on humans, humanity, and human behavior, this film and its visuals are an incredible installment in the breadth of cinema.

6. The Burmese Harp (1956)

Another overlooked director in Asian cinema is Kon Ichikawa. His most famous work, The Burmese Harp, was released in 1956. A very honest and bleak yet beautiful and hopeful tale, this is a remarkable statement about morality.

The film surrounds a troop of Japanese soldiers and takes place during the final days of World War Two. The group must come to terms with the fact that Japan has lost. One particular soldier is tasked with finding another group of soldiers who are holding out in a mountain and convince them to surrender. Faced with a difficult combination of the feeling of failure, unrelenting pride in your country, and unwavering honor, the soldier adopts the life of a Buddhist monk. Unified by music, this film is an unforgettable journey through the experience of defeat.