There are a combination of reasons why some masterpieces fly under the radar, are overlooked, or pass quickly from people’s memory. One factor that rings true for many of the following films is that they come from countries enfolded in political turmoil, limiting their distribution. Several of them are Eastern European and others have directors who hail from colonized countries.

Another reason these films have not received the recognition they deserve is that they break from the trends of the period in which they were made, preferring instead to stay true to the artistic vision and convictions that concern their directors. Innovation sometimes needs time to be appreciated. Lyrical storytelling, scathing satire, and mesmerizing performances are just a few of the descriptions that characterize these forgotten masterpieces.

1. All My Good Countrymen (1969)

A more sober entry than other New Wave Czech films, Vojtěch Jasný’s All My Good Countrymen plots the immediate postwar euphoria of a provincial town and the erosion of their hopeful spirits when the communists tighten their grip on the country year after year.

The film is a pastoral elegy that traces the declining mood of the characters through seasonal landscapes. In the opening moments, a group of drunk locals lay in the lush pastures under the summer sun. Close-ups on frozen flower buds, or in one surreal moment, an abundance of white foliage burying a disoriented villager, start to replace these earlier idyllic images. These scenes function like watermarks that differentiate the acts of the film, becoming progressively sorrowful as the proletariat farmers, one after the other, lose their properties to communist bureaucrats.

Jasný replaces the symbol of the hammer and sickle, which the soviet dictatorships appropriated. He substitutes the daisy that grows naturally in the hay fields the villagers reap as a symbol of proletarian solidarity, referring back to it several times as a touchstone that connects his characters to the earth, and the freedom they harvest from it. This work of social realism doesn’t idealize provincial life. Rather, it laments its loss of innocence.

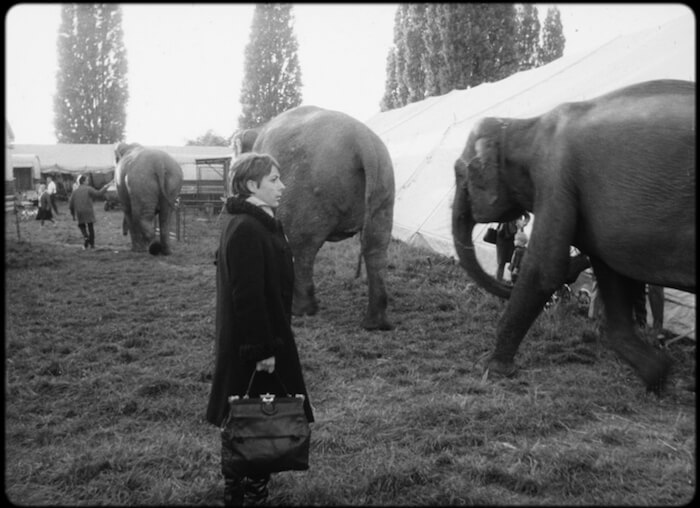

2. Artists under the Big Top: Perplexed (1968)

As the title of the film suggests, its assembly of various forms is perplexing. It is a cinematic successor to the Dadaist art style that was at the height of its power during the Weimar period in director Alexander Kluge’s native Germany. Kluge has no limitation in what other art forms and media he draws from, overlapping, reconfiguring, and combining these disparate elements in jarring and ingenious ways. Passages of philosophy are commonly read while the action is unfolding, which will then cut to documentary footage, and from there transition to newspaper or magazine clippings. The film opens with newsreels of Hitler at a parade bafflingly synchronized to a Spanish cover of The Beatles song “Yesterday.” It is a tongue-in-cheek tornado of multimedia.

The adherence to the principles of collage and photomontage combust into a chaos that matches the carnivalesque insanity of the circus that forms the film’s main plot thread. For a film that focuses on a struggling circus and exasperated out of work actress Hannelore, it is only appropriate that it also functions as a large tent that captures the confused frenetic energy of the director’s absurd methodology. It is a truly composite film.

Difficulties with regulators and festival organizers form the subject of Kluge’s satire, but it is also why the film veils its critique in the abstract. For this reason the film is ambivalent and speculative. Between the reoccurring images of the circus tent lethargically falling to the ground and the actress who is asked to work for free, Kluge personifies the creative frustrations he experienced in the blighted filmmaking landscape of postwar Germany. There is also a lot of idle time, false starts, new opportunities that then quickly flounder. These abrupt starts and stops also follow the pace of the life of an artist under the West German regime that was still trying to find its footing in the post-war years.

3. Black Girl (1966)

Based on a real-life event, in a film that runs less than an hour, Senegalese director Ousmane Sembène summarizes the legacy of racial injustice in the post-colonial world. A Senegalese woman moves to the south of France, working as a live-in guardian for the children of a wealthy family. Other than ordering Diouana around, the family she lives with greets her with downward glances and slamming doors. This silence snuffs Diouana’s presence in the home, becoming a microcosm of the willful ignorance of postcolonial society to remember the imperialist exploits of their colonial past. Absent of memory, discrimination continues. Diouana spends little time with the children, delegated to servile tasks of housework and fulfilling the demands of the family whenever they ring their servant’s bell.

Dissonance sets in when it becomes clear the arrangement is one between master and slave, trapping Diouana inside a rigid social hierarchy that considers her less than human. In the land of the colonizer, where Diouana comes seeking freedom independence, the social inequities of racism imprison her further than in her native Senegal. After it is too late, the family tries to pay money to remedy the harm they cause, but respect, dignity, and equality are not things money can buy. As Sembène critically points out, economic means cannot resolve the cruelty and violence of a racist mentality. A sparse number of characters and a minimal plot creates space for attention to be paid to small details that speak volumes.

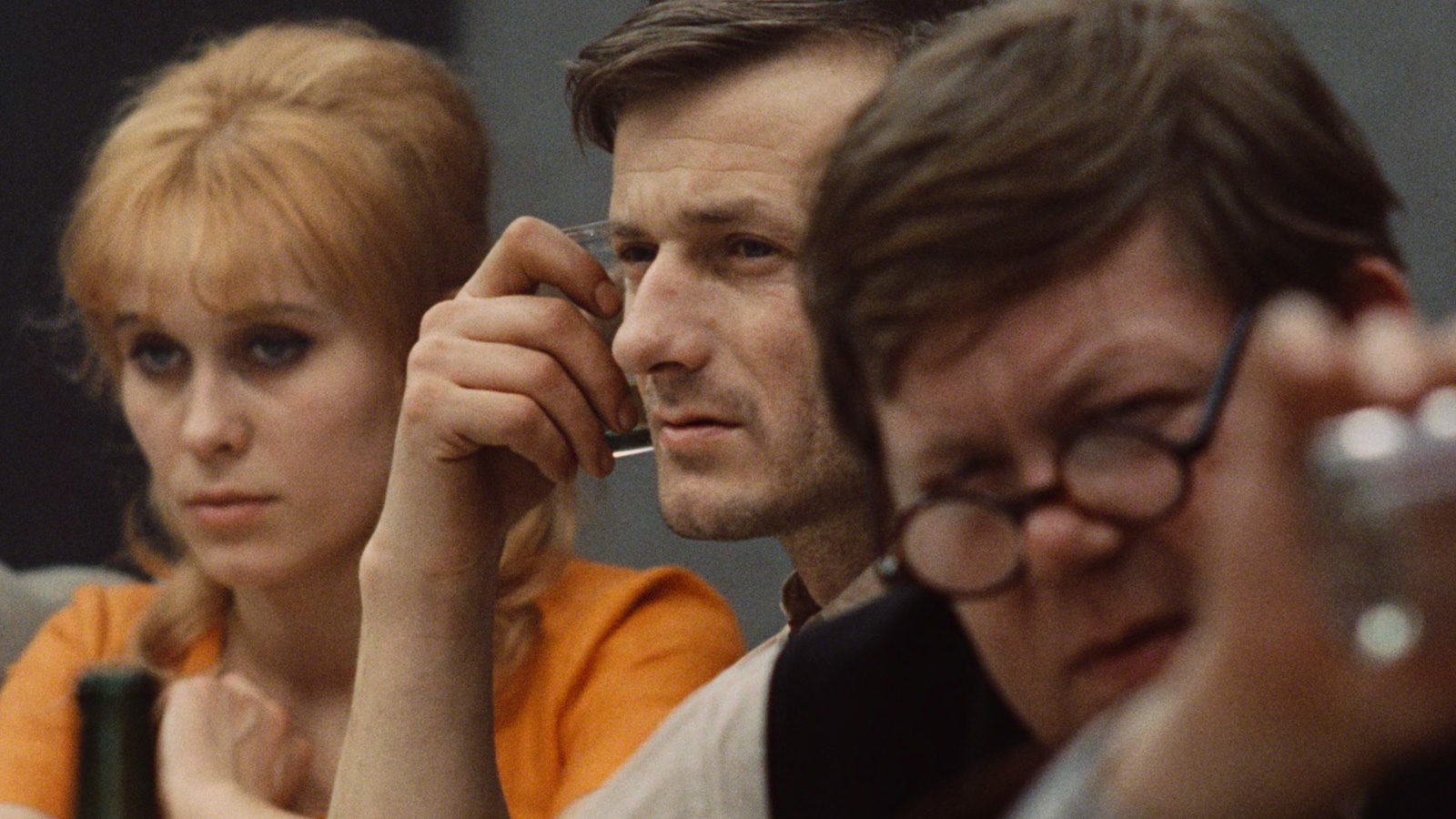

4. David Holzman’s Diary (1967)

Jim McBride’s mockumentary grapples with the darkness he perceives inherent in the art of filmmaking. An aspiring out of work filmmaker crosses the ethical boundaries of personal privacy in search of the medium’s voyeuristic power to create meaning. He comes up empty-handed. His frustration at his failure to uncover a higher truth, and the relationships he destroys in the process, document the volatility of the artistic process, the moral conundrum of what should and shouldn’t be filmed, and the psychosis that possesses a director when trying to realize their artistic vision without consideration of the cost and effect on other people.

The machinery of Holzman’s art, namely the camera, becomes a specter that haunts him. The camera becomes a Mephistophelian entity that Holzman enters into a “deal” with in Faustian fashion. The promise of the medium’s potential to uncover an artistic truth in the quotidian banalities that it records drives Holzman crazy, pulling his hair out at the cutting table, searching for something that exists but that he cannot for the life of him see.

5. Innocence Unprotected (1968)

An unprecedented work of historical realism from Yugoslavian director Dušan Makavejev that uses an unusual editing style that is initially hard to make sense of, but a narrative slowly emerges and comes into focus despite the unusual editing process. There are three timelines in the film each told through separate types of footage: a sitcom the director produced during the Nazi occupation that the communist regime has since suppressed, film negatives chronicling the atrocities of the war in Yugoslavia, and then a present-day documentary of the filmmaker and his colleagues recalling the rebuilding and turbulent changes to the way of life in Belgrade from the pre to post-war communist periods.

Most of all the film is an elegiac ode to the days of independence when Belgrade had autonomous theaters, circus, and television programming not under the control of a foreign power. It establishes its tone with a melancholic smile, exhibiting a farcical cast of local performers at scattered intervals, nodding to the silent era with the aid of intertitles to tell their stories. The film is a nostalgia piece that chronicles the hardships of the mid-twentieth century, championing Belgrade as a cultural center for the arts that outsiders try to straitjacket.