Robert Bresson (1901-1999) was among the most unique directors of the European arthouse, with a working theory of cinematic purity (outlined in his 1975 Notes sur le cinématographe) that rejected all the dramatic convention he considered archaic holdover from the theatre, to make exclusive use of the unique capacities of the film medium, namely the narrative power of editing, and the documentary capacity of the cinematic image to capture truth in unadorned reality.

Often called a minimalist – and sometimes an ascetic for the spiritual grounding of much of these ideas – Bresson sought to capture the human subject removed of all the falsity of acting, believing the cinematic subject found its agency in the edit, – the movement and juxtaposition of discrete gestures – and that the actor contained in their natural expression an individual essence far stronger than any dramatic persona. To this end he liked to cast non-professional actors (referring to them as models) to get around the trained theatricality of the professional actor and to avoid the associative qualities a celebrity brings to a role. Often he would have his models run through their scenes repeatedly to the point of automatism, emptying the act of all but most essential and impersonal gestures. His films are immediately recognizable for the sedate even uncanny acting these methods produce, as well as for their brisk pace and elliptical edits, short runtimes, and the often omniscient, even ironic perspective of his camera, which tells its story through the association of simple significant images – close-ups of faces, hands, and plot-objects – each a piece of the unfolding story.

Little of note is known of Bresson’s personal life, other than his early practice as a painter, experience as a war prisoner during the Nazi occupation, and the late start of his filmmaking career (after a brief experiment in short comedy) with his direction of the religious melodrama Angels of Sin, in 1943 at age 42.

Though in developing his style he would quickly abandon the theatrical mode of this first effort, its thematic concerns with the question of God, sacrifice, and redemption would mark his entire career, which explored spiritual themes from an increasingly agnostic and existential perspective in an increasingly secular world. Basing most of his works on literary sources, the Christian existentialism of Dostoyevsky gave great expression to many of Bresson’s concerns, in at least three, arguably five adaptations. Bresson’s films are frequently the stories of tormented, persecuted, and victimized individuals within predatory and uncaring societies, beneath the increasingly uncertain gaze of God.

Though even as Bresson’s material became darker his films never became graphic, the brutal acts that many of his films pivot on are never shown directly, often skipped over entirely, and so spared the exploitative aspect of arthouse provocations like those of Michael Haneke or Lars Von Trier. His narratives can almost be split cleanly between first-person internal dramas, in which conflicted characters at some sort of crossroads make sudden decisions that lead to their redemption or demise, and panoramic narratives, that show an interconnected cast of characters, often less self-possessed than those of the internal narratives, and the ways in which reverberations of fate and circumstance draw together and drive their lives. In his later work, and especially his final film, L’argent, there is a union of these modes.

Widely lauded by contemporary critics and filmmakers alike, including Jean-Luc Godard, Andrei Tarkvosky, Ingmar Bergman, and Jacques Rivette, and influencing the following generation of filmmakers in Paul Schrader, Michael Haneke, Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, among countless others, his ascetic style, for its opposition to all the standard conventions of cinema, was never directly transmitted, (save for the almost parodic imitation of Haneke’s The Seventh Continent) and masterworks like A Man Escaped, Pickpocket, Au Hasard Balthazar, and L’argent remain expressions of a creative vision unique to the whole of film.

1. A Man Escaped (1956)

In an unlikely alignment of Bresson’s style with the genre sensibilities of the “prison break” film, A Man Escaped may be Bresson’s only truly mainstream work while also arguably his first and fullest expression of the asceticism his whole career worked toward, both feeding and feeding on the genre mandated tension and stoicism, and finding in the prison setting a readymade stage for dramatic allegories of the spiritual.

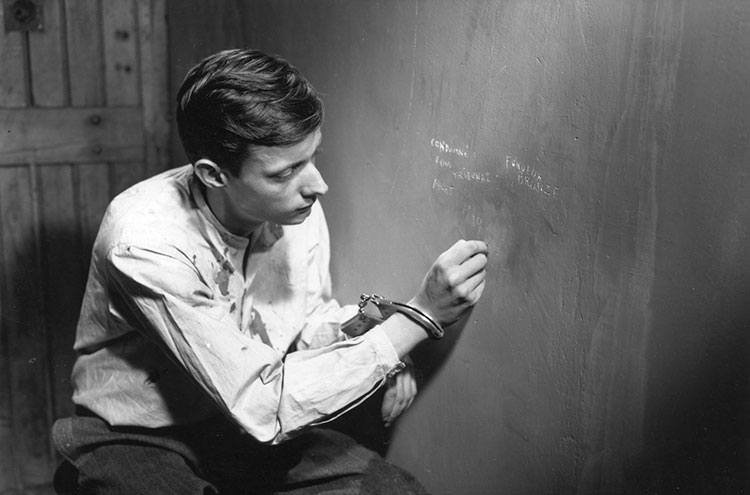

Adapted from the memoirs of French resistance fighter André Devigny’s, A Man Escaped is a first-person procedural account of Lieutenant Fontaine’s (François Leterrier) escape from a nazi prison camp. The use of repetition and routine familiarizes us to the exact dimensions of Fontaine’s captivity, and the means and materials at his disposal with which to escape. It’s so much more satisfying then to see the plan come together, step by step, as Fontaine and cellmate Jost (Charles Le Clainche) construct their tools of bedsheets and springs and push the boundaries of their captivity in scenes patient, tactile, and tense, verging on the ritual – the passing resemblance of a grappling hook in construction to Christ’s crown of thorns is one of many not so incidental images of meditation.

Salvation is not found but built toward in the slow recovering of one’s own dignity. Fontaine breaks his cuffs, then replaces them. What matters isn’t the cufflessness, – he has to play the guard’s game long enough to escape – but the wearing them by choice — freedom of the body follows freedom of the mind – freedom of mind a submission to reality.

A perfect articulation of Bresson’s vision in courage, cunning, and suspense, A Man Escaped is essential Bresson, and a true story to boot with shades of autobiography.

2. Au Hasard Balthazar (1966)

Au Hasard Balthazar chronicles a slice of provincial life through the impassive eyes of a donkey, the titular Balthazar, as he changes hands from master to master, used and abused and silently bearing his burden.

Through Balthazar we meet the members of the town around him, from his first owners for whom he is raised from infancy as a family pet, cared for by Jacques (Walter Green) his siblings, and neighbor Marie (Anne Wiazemsky), to the cruel delivery boy Gerard (François Lafarge) who takes sadistic pleasure in burning him, and the alcoholic farmer Arnold (Jean-Claude Guilbert) among others, each with their own use for Balthazar and own story.

Each visited through the years by turns of good fortune and tragedy: Marie’s father (Philippe Asselin) faces groundless accusations of fraud which destroy him, Jacques finds his way into a life of unfulfilling responsibility, the innocent Marie suffers abuse and assault at the hands of men, the repentant Arnold comes into money, only to die that night celebrating, while the increasingly criminal Gerard goes long unpunished, each as helpless before fate as Balthazar before his masters, each watched by his impassive eyes as indifferently as God’s. And yet Balthazar in his simple perseverance stands for something more as well, the holy fool, the beast of burden, perhaps a saint, the ultimate overcoming of life.

The most loosely panoramic of Bresson’s films – even L’argent directly fixed to the reverberations of a single wrongdoing – it is also among his most ambiguous and searching, continually born to new meaning, and in its relaxed pace, pastoral reprieves and reflections on the passage of time, it manages somehow, to find beauty in the suffering, and not be altogether despairing.

3. Diary of a Country Priest (1951)

The culmination of Bresson’s work in melodrama – following the mostly conventional Angels of Sin and Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne – and his final use of professional actors, Diary of a Country Priest, from George Bernanos’ novel of the same name, also establishes his mode of existential character study, its motifs and conventions of the strictly single perspective of the priest (Claude Laydu), the exploration of psyche through diary and voiceover narration, and the film’s dramatic grounding in the internal movements of the priest’s spiritual condition, and the way these influence his relation to those around him.

Diary of a Country Priest tells of a young priest entrusted with with the care of a remote parish. Unlike the self-assured zealot Anne-Marie of Bresson’s first film, the unnamed priest, (looking a little like Johnny Cash) is a man rended by doubts, shaded by pride, fear, and a desire to be loved, frustrated by politics, tortured by illness, and given a flock who does not want to be saved — a mission without an end. The authentic struggle of spirit cannot be shown in the simple dramatic narrative of Bresson’s early melodramas, it is so much more than that, which is precisely what this obsessively internal mode and the words of Bernanos provide — all the rooty logics of the mind and thrashings of the spirit before the unknown in God and absurd in creation.

This is not the minimalist Bresson we know, formally or thematically, but a wordy and ponderous Bresson working in the theatre of Bergman, expounding a concrete crisis of faith to its absolute ends. It can drag for that, but why shouldn’t it? Bresson would never be so doctrinal again, nor again give philosophical dialogue such precedence, (except in The Devil, Probably whose atheistic protagonist may well be a kind of thematic fulfillment of the priestly type) but even as a work of early style the dramatic power of Diary ranks among the best of Bresson’s, and alongside great works of faith on film, like Bergman’s Winter Light and Dreyer’s Passion of Joan of Arc.

4. Mouchette (1967)

From a novel by the same Bernanos as Diary of a Country Priest, Mouchette almost looks to be Bresson’s 400 Blows in its story of a poor and ostracized country girl that quickly takes a turn for the miserable. A more complete work of Bresson’s total vision than Priest, Mouchette exists at a mid-point between Bresson’s internal narratives – Mouchette’s inner state central to the film’s drama though never verbalized – and his panoramic, the camera breaking from its primary subject now and then in an episodic freeform that explored the shared miseries of several characters around Mouchette in a parable-like simplicity.

Mouchette’s (Nadine Nortier) life is subject to the conditions of her poverty, not only poor living but exclusion at school too, by both students and teachers, as well as the rule of her alcoholic father (Paul Hebert) and the responsibilities of caring for her ailing mother (Marie Cardinal) and infant brother. But she suffers most at the hands of the uncaring and predatory adults around her. And after suffering an assault by the town drunk Arsene (Jean-Claude Guillbert), with whom she had previously offered a misanthropic sympathy, she is criticized for it by the town’s men and women, and pushed to the absolute margins where only one escape remains possible.

One of Bresson’s bleakest films, Mouchette is a meditation on predation and suffering perfectly embodied by the defiant Nadine Nortier, and executed by a master director now confident in his minimalist form. Bresson’s last black and white film it is also his last in the bucolic of the old world and its readily religious imagery – save for the brief venture into Lancelot’s age of myth – before turning his sights to the inscrutable landscape of postmodern Parisian urbanity that would backdrop the rest of his films.

5. Pickpocket (1959)

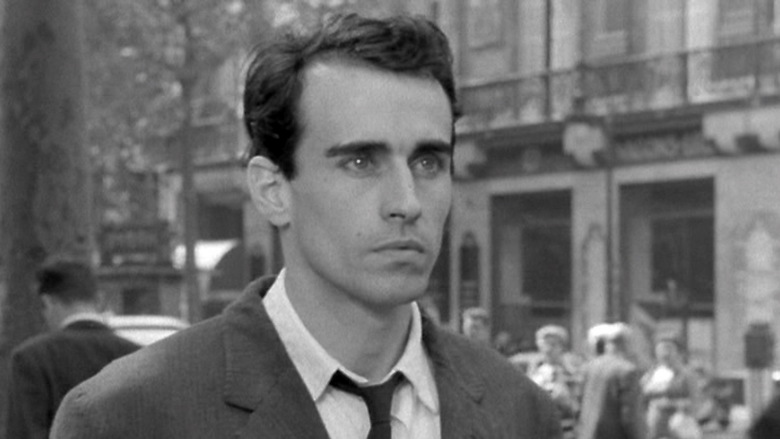

Transposing Crime and Punishment to modernist Paris Bresson does the great existentialist origin story not with the severity of the murderer but the light touch of the pickpocket. Where Diary of a Country Priest gets a philosophical heft from its elaborate dialogues on Christian doctrine, faith, and God, Pickpocket for its part – now in the full swing of Bresson-ian minimalism – achieves an almost aphoristic quality in the sparseness of its dialogue and abstract simplicity of its philosophy. Pickpocket’s Michel (Martin LaSalle) does far less to articulate his inner experience than the priest as he moves into and then back out of a life of crime – or out of and back into a life within Society.

What Michel does articulate is his support for a theory of just crime, a belief that certain individuals finding themselves superior are compelled to forgo the laws of society and set an upside-down world right again, though it’s not at all clear what Michel means of this, suggesting both a leftist emancipation of the many ruled over by the few, or a Nietzschean conquering of the ubermensch over the rule of the average— probably in Bresson’s world there is no difference, only the gesture towards transgression, an affront to the social/moral norm, and in any case Michel’s only invocation of justice. His theory, though invoking some right-order for the world to be reset to, is only ever used to enable and exalt his own selfish petty-thievery, even as he puts this money to the support of his mother (Dolly Scal), and later Jeanne (Marika Green), it is only as cheap replacement of the actual attention and affection he owes, and refusing honest work from the well-connected Jacques (Pierre Leymarie) it is by no means theft by necessity.

Maybe he is only drawn to the transgression itself then, that very sense of being apart, its transcendence of the everyday, or a perceived meaninglessness of the everyday – the creation of one’s own world and values; the death of the father, the state, the murder of God. And who can deny the thrill of the pickpocketing scenes? Both the tense predatory game of his solo career and the coordinated, professional spectacle of gang-thievery are kinetic and tactile. (Which it seems Bresson may well have nabbed himself from Sam Fuller’s 1953 Pickup on South Street – and knowing his taste for visual storytelling his admiration for Fuller’s brand of pulp seems more than plausible.) Is this not the existentialist hero for who thievery fills some void? This is after all the Paris of existentialism, rundown rooms and men in shabby suits, an atmosphere of stale air, brooding, and sudden action.

But as thievery is his first transcendence before becoming a world of the everyday itself, what was once a liberation becomes work, becomes incorporated, and cause for persecution, capture, which Michel seems, if unconsciously, to willingly lead himself into, begins his second, a transcendence of this dead-end world of crime and possibly the meaninglessness of the everyday that first drove him to it. In a familiar motif of Bresson’s, prison is for Michel a divestment of will and worldly possession (his necktie) breaking him down to pure and plastic spirit. And only from there confessed of his sins and robbed of his independent identity as a thief can Michel finally pledge himself to Jeanne, and through her find a release to which the tension of the whole film seems to have been building – signaling if not spiritual redemption, (if not God,) a responsibility in love, and reason to look to the future.

The connective tissue between Dostoyevsky, and the modern existentialist film in Taxi Driver (which Schrader would go on to model a number more of his films after) it is another of Bresson’s strongest expressions of personal aesthetic & vision, and one of his most endlessly entertaining and rewatchable.