What is the measure of a genius? How many masterpieces must a director make so that they may be officially accepted as canon as “one of the greats,” to join the pantheon of major cinematic auteurs?

The career of John Frankenheimer begs that question. Active for almost 50 years, the vast majority of his films are unessential, subpar work; a lot of glorified filmed theater (like his adaptation of “The Iceman Cometh”) and made-for-tv movies that are only celebrated when taken in comparison to its peers at the time. And even in his very worst efforts, Frankenheimer was always a filmmaker of immense, self-evident talent; a craftsman of the highest order.

And it is universally agreed upon he was responsible – in the ‘60s, the heyday of his career – for a few iconic classics and at least one movie that several critics and scholars would argue can be considered as one of the best films ever made (you’ll see it at the number one spot on this list).

With all these said, Frankenheimer may not be ordinarily considered as one of the great American auteurs due to his erratic career, but in his best movies he can stand tall with any of the most celebrated directors adored today. A great artist who should be more valued.

10. 52 Pick-Up (1986)

A Canon picture written by Elmore Leonard and directed by John Frankenheimer; “52 Pick-Up” is a match made in sleaze heaven that delivers in every way that a savvy genre fan could expect out of those names.

Leonard’s plot, which mixes pornography, blackmail and murder, is grimy even by his standards; thankfully, Frankenheimer is intelligent enough not to try to “elevate” the material in any way, which would be a disservice to the proudly nasty heart of the story. Instead, the director fully invests in the grindhouse nature of the narrative, staging sequence after sequence of comically over-the-top sordid behavior, from a porn star party that borders on a orgy to a sequence in which the protagonist is forced to witness a video of his mistress being brutally murdered.

If reading this description makes you suspicious of the movie’s quality and intentions, don’t worry: what could’ve been in bad taste and just unpleasant in the hands of a lesser filmmaker is made by Frankenheimer’s knowingly cheeky tone into a entertaining B crime film that is never ashamed of what it is, but also never revels in the misogyny that can so often be omnipresent in the genre. The platonic ideal of a Canon movie.

9. Grand Prix (1966)

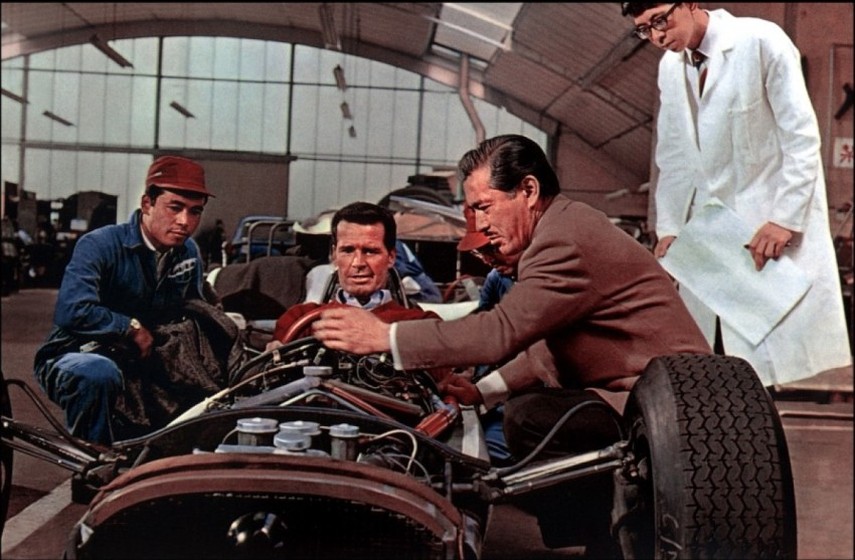

This three-hour racing epic starring Steve McQueen has been largely forgotten, no doubt due to its herculean length and fringe subject matter. It’s still nevertheless a landmark of action cinema, one that continues to influence filmmakers to this day, even if they don’t know they are stealing from it directly.

Frankenheimer, of course, is one of the best and most important action directors of all time, his car chases in “Ronin” being some of the most celebrated in the history of the genre. But, good as they are, his most pioneering efforts regarding the art of filming speeding machines comes in “Grand Prix,” in which his practical and stylistic choices led to a number of technological advancements that set the bar for cinematic depiction of car chases. The level of verisimilitude achieved in the racing scenes in this movie was revolutionary, something never seen before, because those were real cars actually speeding – which may seem like commonplace today, but it was a somewhat unthinkable practice at the time, at least on this scale, with so many moving pieces.

To capture that, Frankenheimer and cinematographer Lionel Lindon basically invented a whole new visual language, carefully choosing angles and lenses (and creating new camera rigs) to fully transpose the vehicular mayhem to the screen. “Grand Prix” may not be particularly notable or exceptional in any way outside of its action scenes, but it’s directly responsible for the rise of real, practical stunts and for the visual grammar of car chases. So it is a seminal film, in that sense, one which cinephiles should seek out if only to see the boundaries of cinema being expanded right in front of their eyes, in real time.

8. Dead Bang (1989)

Sometimes you don’t need to subvert genre cliches to make them interesting; there are plenty of occasions in which executing them with gusto and conviction is enough to reinvigorate even the most tired of tropes.

“Dead Bang” is a classic, clear-cut example of a film with next to zero interest in going against the grain of what is expected of a standard lone wolf cop movie (though it does add some interesting emotional texture to the archetype) and instead makes the most polished version of that possible. Frankenheimer, at this point in his career relegated to making gun-for-hire projects largely beneath his talent, gets an opportunity here to demonstrate his skills as an artisan of action and tough guy poetry. The film may be far from being one of his most personal pictures, but it’s a perfect demonstration of what the auteur theory is really about: a director with personality who is able to put their stamp even on second-hand material.

And “Dead Bang” is very much a John Frankenheimer film, unmistakable once you see those crooked, sweaty close-ups or the wild, expertly staged action sequences; there’s an all-timer foot chase in this movie, among many other magnificent set pieces. Among his various qualities as a filmmaker, Frankenheimer is one of the best action directors to ever get behind a camera, and this film is one of his finest efforts in the genre.

7. The French Connection II (1975)

The original “The French Connection” was an odd beast: a modestly ambitious procedural that, by virtue of being so exquisitely crafted and acted, was elevated all the way to Best Picture winning glory. But it was still essentially an action movie, one that, despite whatever awards prestige it encountered, still had the potential to be a franchise.

And so we have “The French Connection II,” a sequel that attempts to bridge the gap between commercially viable, audience-pleasing cop movies and more artful virtues, using the continuing story of Popeye Doyle to explore the war on drugs and the effects of drug addiction. Those two things don’t necessarily always work together; as many critics noted at the time, the sequence in the middle, in which Doyle is detoxing from heroin, is very powerful on its own, but stalls the overall pace of the narrative.

But it is precisely those little idiosyncrasies and contradictions that make this a special film on it’s own: though it is in many ways a natural continuation of the first movie, “The French Connection II” is determined to do its own thing. It doesn’t replicate the breakneck pace or the acidic irony of William Friedkin’s approach, substituting his sardonic, economical style for a more subdued character study, taking time to flesh out Popeye in between the (excellent) action scenes. It’s definitely not as good as the original, but Frankenheimer deserves recognition for having the guts to make the movie his own.

6. Birdman of Alcatraz (1962)

Frankenheimer had one of the best directorial runs in the history of American cinema in the brief but creatively fecund period between 1962 and 1966, during which he released practically all of the movies for which he’s now most remembered and celebrated (and which comprise the top half of this list).

Of those, “Birdman of Alcatraz” is the odd one out: all of the director’s classics from that time are either paranoid political thrillers or high octane action movies, whereas this is a straight drama, an introspective, compassionate portrait of life in prison. The film is nominally a biopic of Robert Stroud, a criminal who became notorious due to the attachment he created with birds throughout his long incarceration period. But the truth is that the filmmaker took that concept and crafted a fictional character/story from it; the liberties taken with Stroud’s life are so numerous that one could make a whole other movie about the real man.

Thankfully, that’s absolutely irrelevant in the face of this film’s artistry, which is anchored by Burt Lancaster’s achingly vulnerable performance (one of the rare actors who could play tough guys and quiet, internal men equally well) and Frankenheimer at his most understated, but is still a visually sophisticated effort from the era.