Is there a more recognizable voice in contemporary American cinema than this quirky Minnesotan duo? Ever since they burst into scene in 1984, the Coens have established themselves as one of the most prolific and unique auteurs working today. Their films are perfectly accessible and enjoyable at a surface level, but sufficiently layered and clever to stand the test of time. Beyond their infinitely quotable characters full of wit and wry deliveries, their explorations of the fascinating singularity of the average man always come with a healthy dose of existentialism.

To understand their work is to forego any hope of labelling it under any kind of genre, because their chameleonic style seems to be deliberately designed to mock and subvert any expectation or overused trope. Their oddball comedies are bursting with self-awareness, dry humor and referential gags, with misdirection as their biggest ally. But even for their unmistakable flair, just like any worthy filmmaker to ever pick up a camera, they have drawn inspiration from great films of old, with the following being the most crucial in shaping up the work of the Coen Brothers.

1. Dr. Strangelove (1964)

Stanley Kubrick’s classic comedy has been repeatedly cited as one of Joel and Ethan’s favourite films, and for good reason. It’s easy to see why this take on the absurdity of war is right up their alley. Kubrick managed to shed light on the hypocrisy of bureaucracy and diplomacy by presenting a ludicrous but not quite inconceivable situation amid the Cold War hysteria, perfectly capturing the frightening prospect of mutual destruction of the time. The humor and the idiosyncratic use of language by Dr. Strangelove, full of rapid-fire comebacks and sassy catchphrases is pure Coenesque style.

And it’s safe to say the Brothers love that time period as they also had a crack at the Red Scare of 50’s Hollywood with Hail Caesar!, where a group of Communist screenwriters secretly abduct a movie star for ransom, only to be hustled by a Gene Kelly-esque actor who’s also a Soviet sleeper agent. But if there’s a Strangelove spiritual successor, it’s Burn After Reading, their hilarious black comedy where two dense gym employees confuse some lost memoirs by a retired CIA agent with classified government documents, launching a loop of misunderstandings and bureaucratic nightmare.

2. North by Northwest (1959)

This Hitchcock film can’t be reduced to one genre, it’s equal parts an espionage thriller (poking fun at Cold War-paranoia), road film and romantic comedy (who could forget its masterful ending train gag). You could even argue it makes for a better James Bond movie than any Bond movie ever released.

But if it paved the way in any way, it is in the concept of a naive bystander, an Average Joe who mistakenly finds himself embroiled in a whirlwind of misconceptions that escalate into a full-blown whodunit. If that sounds familiar, it is because Fargo, The Big Lebowski, The Man Who Wasn’t There and so many Coen hits have perfected that same trope. There’s a particular gag in The Big Lebowski that pays homage to Hitchcock’s film in which The Dude is looking for clues and scribbles on a notepad, channelling his inner Cary Grant, but with stranger results. Whereas Grant finds vital information, The Dude reveals nothing more than an inconsequential kinky drawing.

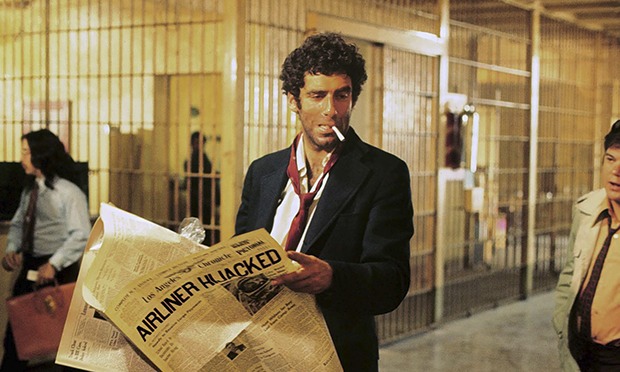

3. The Long Goodbye (1973)

It’s safe to say that Jeff Bridges’ ‘The Dude’ persona in The Big Lebowski owes a lot to Elliot Gould’s wisecracking, off-beat private investigator in Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye. Both characters are fundamentally modest and down to earth, sharing the same hippy-dippy goofiness and laid-back demeanour that feels out of sync with their surroundings and position, as they both try to untangle a labyrinthine mystery in Los Angeles.

These two leads are deliberately unconventional in a conscious effort by both films to subvert the immaculately smart and charming detective archetype seen in most of old pulp movies. Altman’s own dig at the classic noir is a reimagination of a Raymond Chandler novel, who at the same time is cited by the Coens as a loose inspiration when coming up with their essential Gulf War satire.

4. Double Indemnity (1944)

Double Indemnity is one of Billy Wilder’s sharpest scripts, one of those noir films that makes you go: “they don’t make ‘em like that anymore”. In a nutshell, an insurance salesman on a routine house call meets the wife of a client, later plotting together the death of her husband in order to cash out on an accident insurance policy and a double indemnity clause, fabricating it to make it seem like a fortuitous casualty.

Any decent filmmaker with a set of eyes and ears can easily draw inspiration from this movie in how to make an A+ script. Wilder’s fatalistic statement on how easily people can be corrupted by greed is a recurrent motif that can be found in dozens of Coen movies, including their neo-noir debut, Blood Simple (which also borrows the idea of a car stalling while leaving the scene of murder). But the most direct influence has to be in the maze of legal mumbo jumbo seen in Intolerable Cruelty and The Man Who Wasn’t There, which are full of marital clauses and mischievous farse.

5. Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936)

If there’s a common trait among Coen characters, it is their unorthodox, verbose expressions and wry deliveries. This type of verbal comedy often clashes with their surroundings, as they’re often oblivious to the dangers and coincidences they are subject to. One big example of such a character tumbling his way to success is simple man Norville Barnes, the zany lead in the Brothers’ screwball comedy The Hudsucker Proxy, where he finds himself appointed as president of a big manufacturer company as part of a stock scam.

Their light-hearted fantasy set in 50’s Art Deco New York is a clear homage and well-meaning parody of Frank Capra’s classic movies such as Mr. Deeds Goes to Town. In this case, both movies follow a small-town, well-spirited young man who heads to New York City looking for opportunities and finds himself acquainted with an attractive reporter, who employs their relationship and trust in order to manipulate him. Honorable mention to Fritz Lang’s Metropolis for the dystopic visual aid.

6. Sunset Boulevard (1950)

Billy Wilder’s take on Golden Age Hollywood follows an unsuccessful screenwriter in LA who befriends a silent-era movie star detached from reality, yearning for an era that is gone forever. The movie portrays a decaying film industry threatened by the change of guard, painted with an eerie surrealism pretty much like the Coens’ Barton Fink.

Barton Fink, set in 1941, also follows a struggling screenwriter suffering from writer’s block, and most importantly, pokes fun at the decay of the film industry in the studio era too with a similar disdain towards big-time producers, and the rift between commercial freedom and creative integrity from a writer’s perspective. Another parallel is the use of the setting; Norma Desmond’s mansion in Sunset Blvd has gone down in history as a symbol of the crumbling city of Los Angeles, an ancient palace stuck in the past. The modest hotel where Fink stays in the movie shares the same claustrophobic, isolated feel to Desmond’s decrepit home, becoming increasingly chaotic as the story unfolds and literally becoming hell at the end.

7. The Killing (1956)

One of the most frequent tropes in the Coen Brothers’ oeuvre is the sheer incompetence of their criminals, often assigned to carry out an illegal, high-stakes task only to fail spectacularly at it. From low-witted hoodlums to boneheaded bureaucrats, chances are if you’re watching a Coen film you’re bound to bump into one clumsy antagonist. And part of their brilliance as screenwriters comes with how they exploit their shortcomings to generate hilarious twists in their stories. And that’s exactly the biggest parallel between their films and Kubrick’s classic noir.

In it, a group of no-good gangsters plot together a big-time heist in the racetrack where one of them works. Needless to say, the scheme is hit by countless of unforeseen inconveniences and Kubrick manages to balance the comedic touch while never losing sight of the heavy dramatic moments. From Miller’s Crossing to Burn After Reading, the crooked gang seen in The Killing shares a lot of similarities with inept Coenesque perps, probably none as glaring as Fargo’s criminal trifecta of Steve Buscemi, Peter Stormane and William H. Macy.