Everyone knows the age of the movie star is over; big studio filmmaking today is driven not by the magnetic power of a single actor or actress, but rather by the name recognition of any given brand, be it a previously successful intellectual property or a literal toy.

There are many reasons for this shift in philosophy, but not the least of which is that there really aren’t many actors today who can rival the sheer screen presence of classic Hollywood stars. That may seem like a broad, biased statement, but ask yourself: is there any current-day performer who can match Paul Newman not only in charm and charisma, but also in genuine talent?

But that’s an unfair comparison, since he was a once-in-a-generation kind of talent – with this list being a mere sliver of his wonderful career.

10. Harper (1966)

What Robert Altman and Elliott Gould did for Philip Marlowe in “The Long Goodbye,” Paul Newman and writer Willian Goldman did for Lew Archer years before in “Harper”: they subverted the figure of the classic noir detective by putting him in a postmodern environment in which his codes have become meaningless.

“Harper,” directed by Jack Smight, is far less radical in its subversion than Altman’s vision, but what it lacks in savvy genre revisionism, it makes up for in unpretentious genre thrills. While the film does seek to modernize and interrogate the tropes of noir, it’s still primarily interested in being a straight crime mystery – something it does wonderfully. Goldman’s writing is typically excellent, seamlessly weaving Ross Macdonald’s complex plotting and sparse but memorable characterization into a cinematic narrative; and Smight, despite being an inexpressive TV director, commands the story with a strong sense of pacing and performance.

Which brings us to Newman. A bonafide movie star who was also a truly intelligent actor, he plays the lead character (with his name changed from the books due to some rights issues) with his trademark charm but also giving hints of an internal depth rarely afforded to this type of character.

9. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958)

Play adaptations are invariably actor showcases. Inherently limited on a visual level and primarily guided by the writing, these films tend to be too heavily focused on the performers in lieu of more traditionally cinematic qualities. Naturally, that’s very attractive to actors; Newman himself starred in many such pictures throughout his career and, of those, none is better than “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.”

Which is ironic, considering both Newman and Tennessee Williams were deeply disappointed with Richard Brooks’s adaptation of the Pulitzer Prize-winning play. Their reasons are famous and absolutely fair: the film completely eliminates the homosexual themes of the original story and creates a new reconciliation scene that neatly resolves the central conflict between Brick and his father Big Daddy, replacing Williams’s adult ambiguity with a Hollywood artificial happy ending.

But while their frustration is absolutely understandable, those elements are precisely what makes “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” the movie, work on its own: this is a classic Hollywood melodrama rather than a failed Tennessee Williams adaptation, and viewing it as the latter is a disservice to Brooks’s handling of the material, which bears a distinct sensibility of the big, broad, earnest ‘50s Sirk-esque domestic pictures.

And most of all, the acting is simply superb, none more so than Newman himself, here shedding whatever movie star vanity he may have had for pure, unadulterated emotional nakedness and honesty; a performance so raw that it becomes the backbone of the film.

8. The Sting (1973)

Every so often, the mainstream style of filmmaking represented by Hollywood finds one movie that perfectly represents their ethos of uncomplicated, easygoing, crowd-pleasing entertainment, and in the early ‘70s, there was no better embodiment of that than “The Sting.”

Hugely charismatic leads; a serpentine plot filled with twists and surprises; a mustache-twirling villain; character-based emotional stakes; satisfying payoffs; a beautiful production design; an iconic score; and so on – there’s little in “The Sting” beyond its surface pleasures, but those pleasures are so numerous and so finely crafted that there’s no reason for complaining.

“The Sting” was one of the last populist pictures made before the rise of the current blockbuster, made in a time when more adult fare was in fashion (a look at the Best Picture winners of the 1970s shows this is the odd one out). It’s the perfect middle ground between those two worlds: entertaining but not mind-numbing, thoughtful but not overly ponderous. They don’t make ’em like this anymore, truly.

7. The Hudsucker Proxy (1994)

Most films in this list are proper “Paul Newman” movies, in the sense that the entire picture is constructed around him and his creative input was such as to make him almost a co-auteur. “The Hudsucker Proxy” is the opposite: this is first and foremost a Coen brothers movie, in which Newman plays a small part.

Therefore, its inclusion here may seem strange, but since the point is to highlight the best movies regardless of the extent of Newman’s involvement, it would criminal to omit the Coens’ wonderful homage to screwball comedies of yore, a film tied with “Miller’s Crossing” for their greatest effort at pastiche. At this point in their career, the filmmakers are not necessarily interested in subverting the Hollywood genres they love as much as they want to genuinely and lovingly recreate them, which they do here with such creativity, style, verve, wit, and strength of vision that it was naturally a complete commercial failure.

Not the least of the film’s many pleasures is Newman as the all-evil corporate villain, a relatively small role that the actor engrandizes by sheer charisma, working out the comedic muscles he didn’t often get the chance to flex.

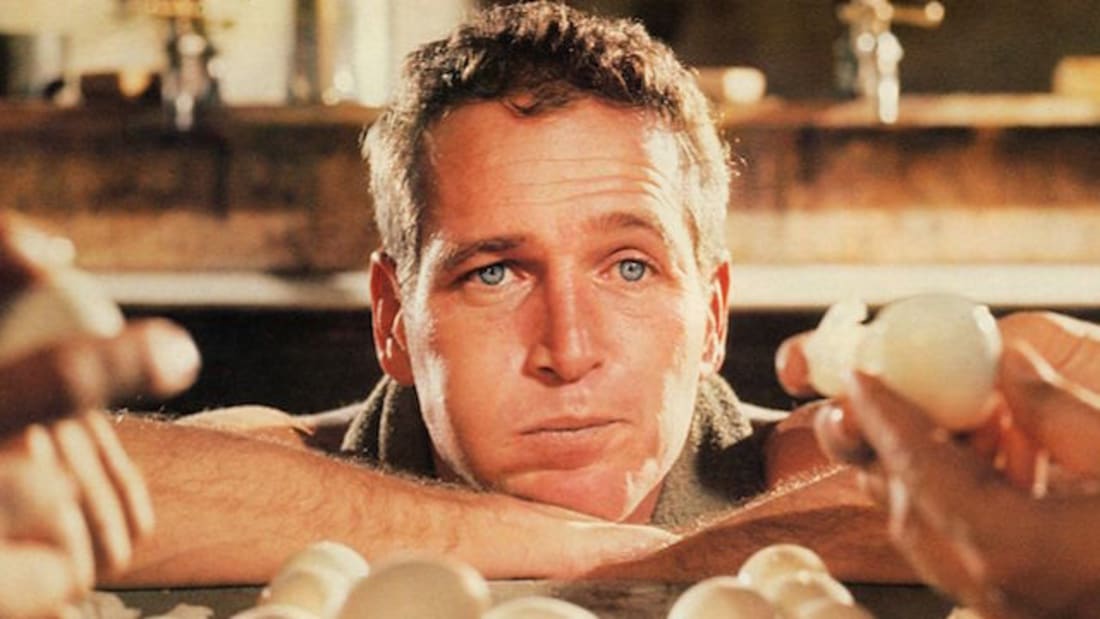

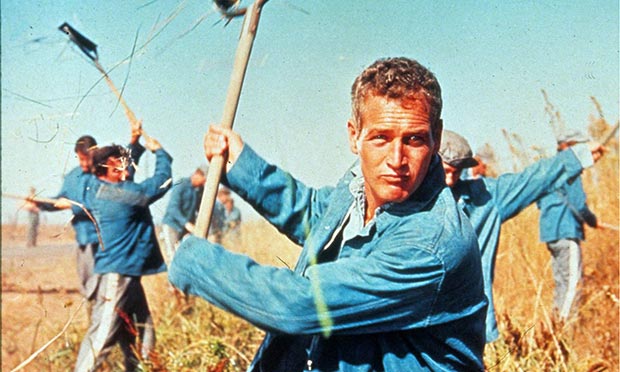

6. Cool Hand Luke (1967)

The 1960s were a very troubled time for American cinema, a period in which the old studio system was starting to crumble but continued to march through making ever-more expensive and overbearing pictures that failed to connect to an increasingly more sophisticated and demanding audience.

“Cool Hand Luke,” much like its steadfastly rebellious protagonist, went against the current: it’s one of the movies most representative of the real ‘60s, a film that perfectly captured the widespread anti-establishment sentiment that defined a decade of political turmoil and social upheaval. Even more relevant and courageous was the fact that the representative of authority in this movie is the prison system and the police itself; it’s one of the very few and very best anti-cop films ever made, especially coming from an industry that thrives in making flattering portraits of that institution.

But the true secret of the longevity and success of “Cool Hand Luke” is that it works wonderfully as a piece of populist entertainment: it’s tremendously funny, teaming with cheer-worthy moments of heroic feats and led by the platonic ideal of what a movie star performance should be. Luke Jackson may not be the most complex character Newman has played, but it’s his most indelible myth of the big screen, the kind of larger-than-life figure that only exists in the movies.

Perhaps because it’s still a Hollywood production instead of an independent effort like “Easy Rider,” the film never quite became a counter-culture phenomenon, being embraced much more by the mainstream. But don’t let that fool you: this movie will always be one of the most furious anti-authority stories out there.