This list will not take a conventional take on 1980s animation films; rather, it has attempted to seek out movies that for better or worse have somewhat been left out of the mainstream radar, or have been forgotten and left unmentioned. This is not because they are not good movies; indeed, many of them have won international prizes and were presented at Cannes or even considered for an Oscar. Rather, they have been difficult movies, hard to understand or define. These include children’s movies that were not so childish, dark comedies that were much too dark, experimental animations that were perhaps too experimental, or spiritual analysis that left too many questions open. Today, with four decades passed, we can give them another look and truly recognize relevant contributions to their dystopian take on the future, its environmental considerations, or simply its purely nonsensical/visionary variations.

A careful reader will notice a golden thread connecting the Hungarian Animation school that has contributed to three of the titles, proving its importance on the international scale (it is worth mentioning that while writing this list, acclaimed director Marcell Jankovics has passed away). Also, it has been attempted to vary the countries of production and not concentrating strictly on US and Japan-based films, though it has been done with quite ease and in respect of quality. As judging was not felt attainable, they are listed by their year of release.

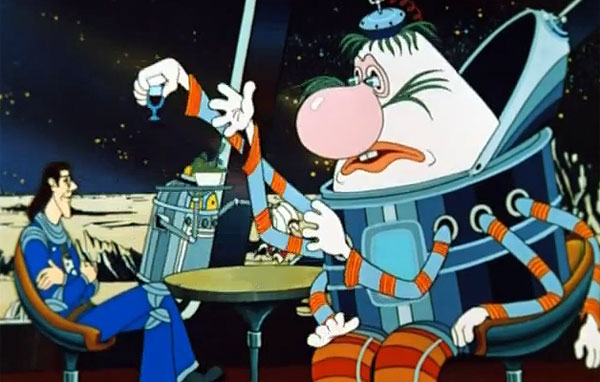

1. The Mystery of the Third Planet (1981, USSR)

In the year 2181, Alisa Seleznëva and her father, Professor Seleznëv, along with pilot Zelënyj, set out on a space expedition seeking rare alien animals for the Moscow Zoo. After encountering fabulous creatures such as a flying cow and a chattering bird, they accidentally get caught up in a space pirate conspiracy of the cruel Doctor Verchovcev.

Undisputed cult animation of the Soviet era (though I am curious of other options and opinions), with proud propaganda behind it, the film is entertaining and juvenile, taking four years of hand-drawn production and a unique synth-induced original score by Alexander Zatsepin. Repetitive releases have been attempted in the US and on European television, albeit with re-dubbings and alterations, shading its sense and possibly shadowing its success.

2. Son of the White Mare (1981, Hungary)

Nominated by some critics as the greatest psychedelic movie ever made, and yet tainted by tragic ‘course’, whereas the restored movie was due to be released in the US in 2020 only to be halted by the pandemic, and its director passed away in the same year. This movie is indeed filled with symbolism and spiritual imagery. It narrates, as with many epic storylines, the quest of the super-powerful Son, a goddess, to avenge and defeat the creatures that have taken over the world.

With over three years of research by late director Jankovics Marcell on Hungarian legends and tales, the movie appears indeed cursed. Not only was it a technical production and budgetary hamper, but it was panned, ignored at its release, and forgotten for decades until its recent 4K restoration. If one allows some repetition in its truly striking imagery, along with its powerful narration and the power of the original dubbing itself, this movie is truly a masterpiece: one we may seek in a peaceful return to the cinema.

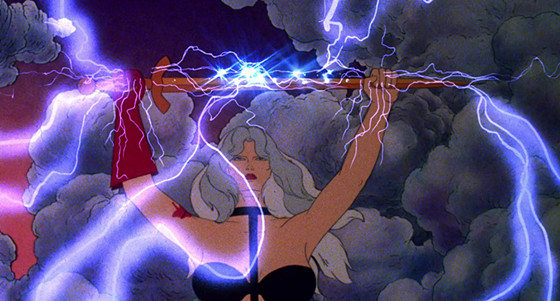

3. Heavy Metal (1981, Canada-USA)

In 2031 a deadly and fundamentally evil green meteorite known as Loc-Nar falls on future earth. After killing her father, it corners a little girl sharing some of his deeds that will be episodes the animation is divided into, from futuristic neo-noir to zombie apocalypse.

A mix of genres and styles that saw an epic collaboration of names such as Moebius, Dan O’Bannon, and Richard Corben, this not-perfect yet now-cult animation has opened a sex-craving, surreal and drug-induced universe, whose atmospheres are rightfully irresistible.

Uncountable are the number of sci-fi movies that will take inspiration from it – one among many is (allegedly) the ‘taxi’ chase in Luc Besson’s “The Fifth Element.” Again, this is not to say the movie is perfect, nor all-in-all enjoyable, or if it actually makes any sense till the end. But that said, just like heavy metal music, when you get down to it is surely a “hell of a ride.”

4. The Last Unicorn (1982, USA)

Perplexed by the mysterious words of a passing group of hunters, mentioning the tragic fate of the last of her kind, the last living Unicorn leaves her magical forest – and thus jeopardizes her immortality – to find the truth of her fate. Facing witches, harpies, wizards, and semi-divine creatures she will seek out the mysterious King Haggard, who might know where all the Unicorns have gone, and why.

Written with an outstanding depth (what an opening!) and playing back and forth with metaphysical considerations over truth, illusion, magic and destiny, this animation is important on an uncountable number of levels, most of which are sadly reduced only to cult status. We have the quality of the animation, somewhat childish at a first glance, then absolutely enchanting and somewhat raw at the same time, inspired (as proven in the opening titles) by renaissance tapestry.

The well-curated visuals, engaging in the character depiction as well as landscaping, are also enriched by a star-based cast of voice actors, with Mia Farrow, Jeff Bridges and Christopher Lee, among others. Furthermore, rendering the animation truly enjoyable for both children and adults, its story is based on an important novel (and screenplay) with the same name by Peter S. Beagle. Last but not least, the producing studio of Rankin/Bass joint with the Japanese Topcraft will later join together to film Nausicaa and establish the world-renowned Studio Ghibli.

5. Time Masters/Les Maîtres du temps (1982, France)

Following a fatal spaceship crash, Claude leaves his son Piel on the apparently desolate planet Perdide, begging him to get in touch with his friend Jaffar, an adventurer of the galaxy. Communicating through a special transceiver, an adventure will take place across space (and time) to save him.

This is the second filming effort of the legendary Rene Laloux, this time with a strict collaboration with Moebius. Here we also see the contribution of the Hungarian school of animation, and the inspiration from the same sci-fi writer, Stephan Wul. The result is not as striking and ‘revolutionary’ (read also political) as the previous “Planet Savauge,” but the visual and metaphysical considerations – along with the scenic visual and characterizations – remain as impressive as ever.