In the 90’s there was Pulp Fiction, and then there was everything else. Pulp Fiction had close to the same effect (without the avalanche of toys and tie-in products) as Star Wars had in the previous generation. But there was one film that brought the Cassavettes to the wood-paneled Tarantino 70’s, a Danish film called Pusher, shot by a 24 year old cinema super geek whose career actually lasted after being birthed in QT’s wake, and which is still going strong.

The other great Megalon of 90’s film experience was the Merchant Ivory picture. Merchant Ivory meant to decriminalize the rich and return to the past glory of the Royals’ England. In MI films all of the characters are of such high morals and so much fiber, they make Jane Austen’s novels look like The Three Penny Opera. Not so with Six Degrees of Separation. These are New York rich. And in this movie, they get spanked.

The 90’s were also the Gay 90’s when out directors plied their craft. Three of the best ever Vincent Minelli, James Whale, and FW Murnau were all gay and closeted Fort Knox style by the studios. Cracks appeared in the 90’s and the great Todd Haynes, Lisa Cholodenko, (others) appeared and show no signs of slowing down. One film handed us the key code to 90’s gay cinema, Poison.

The 90’s brought in a landslide of neo-noir, and percentage wise, pretty quality stuff. Jim Thompson and Dashiell Hammet are great writers, but more importantly to the financiers, inexpensive in bang-to-buck ratio. Dialogue was the key, not blowing up downtown Megalopolis, and the video recoup chances were pretty good. Out of this landscape and tradition comes The Grifters.

Two films taught us that one of the most important things in life is jazz. Both Sweet and Lowdown and Kansas City were criminally neglected in the theatres, and both films were by two directors at their artistic peak, and came between these respective director’s biggest hits, and deserve as much credit.

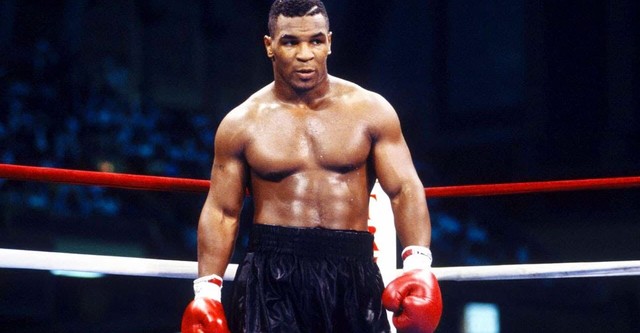

And finally every era has to have a rags to riches to rags story, and in America, redemption. Mike Tyson’s career and downfall is the stuff of Greek tragedy and his redemption is pure American rebound.

1. Pusher (1996, dir. Nicholas Winding Refn)

Pulp Fiction landscape had a bulldog of a challenger which never saw any real states side distribution. Selling a crime film with subtitles is at the very least, a challenge. But Pusher has become a classic. It is a dark, bleak, No Exit drama where we follow Franke (the amazing Kim Bodnia) has to scramble to find the cash and the vig to pay off his supplier, or it’s curtains. Two of the major roles are played by (at the time) non-actors, Milo (Zlatko Burić) is the drug kingpin, and Radovan (Slavko Labović) is his enforcer, the locations are very real and above all, the situations are very, very real. Pusher has to be the best film capturing the underworld of the time, its machinations, and the constant deception and back stabbing.

Pusher was the breakthrough role for Mads Mikkelsen, Denmark’s DeNiro, playing Tonny, Franke’s hapless sidekick. Describing the film any more is a spoiler, but there is a certain magic in the day-to-day scenes sprinkled between hair-raising action and tension. Franke being recruited by his boss Milo to help move a fridge is priceless, along with the scene where Franke has to eat Milo’s horrific cooking; followed by the scene where Franke and Rado, on their way to collect, talk shit about Milo’s cooking. Tarantino performs the same hat-trick, but Refn’s is much less stagey. This, and everything that would spoil Pusher by telling more of the story, makes it unforgettable. See for yourself the first chance you get.

2. Six Degrees of Separation (1996, dir. Fred Schepsi)

This adapted stage play is based on the real exploits by one David Hampton, a black kid who basically took a hefty chunk of New York society for a ride pretending to be Sydney Poitiers’s son. This film features some of American’s best actors, and Will Smith. The script was adapted from the play by John Guare by himself, and directed by Fred Schepisi. Stockard Channing is heart breaking as a woman who can’t find her soul. She is mirrored by “Paul Poitier” (Will Smith), a sociopath so empty that he tries to fill up that emptiness by what and who is at hand. Not once do we see any flicker or hint of who the real Paul is.

It is no accident that he disappears without a trace, because no one knows his real name. At a dinner party (where the extras are actual New York society elites), Ouisa Kitteridge (Stockard Channing) lets go of the reins, and asks out loud what she can do to hold onto experience. Her husband, the shallower of the two, Flanders KItteridge (Donald Sutherland) finds locus in the great masters, as well as the paintings of 2nd graders.

Six Degrees is a hilarious send-up of the rich and their rituals, the best parts are with the spoiled rotten college age children, who got everything they ever wanted but are pissed off nonetheless. (Watch for a young JJ Abrams as Doug, the ungrateful son of a rich NYC doctor).

3. Fallen Champ: the Untold Story of Mike Tyson (1993, dir. Barbara Kopple)

This movie appears to have been created as filler for a Friday night time slot back in the bad old days when ratings were king and there were only 57 channels of tv. Mike Tyson was clearly the most talented boxer of his generation. For any boxing fan, the footage of his early training is stunning. At 13, we see that he is larger and faster than any rising contender in decades. The circumstances from which he arises are pretty stunning as well. Tyson also suffers from mental health issues. The greater society which he finds himself into, specifically Don King’s iron grip on the boxing world, could fill a few volumes on their very own, and have.

Fallen Champ is very far removed from your paint by the numbers sports documentaries. Kopple stays in the place she is filming and talks to the people there, not just about Mike, but the people and the circumstances around him. The first scenes are of pidgeon coups in the Bronx, and two young men explaining pidgeoning. The second scene is two young men talking about “scoring” (ie robbing) given that they are so poor. We see how Mike fits into all of this. This is the blue print for the rest of the film, and is an intricate insight into a controversial man who has recently re-branded himself as a cultural figure and a go-to guy for wisdom.

Fallen Champ has many magical cinematic moments. Where Tyson’s trainer comforts an opponent Tyson wiped the floor with in the Junior Olympics; a fifteen year old Tyson talking about being arrogant, how “…it’s OK to be a little arrogant”; Mike having a depressive episode; these are just some of the few.

We see Tyson choking on wealth and fame. In a recent interview he said the times he spent in prison were the best of his life. Because he had his peace. Out in the Don King world, he had everything and nothing. ‘That’s the way God tests you. He gives you everything you want.”

4. The Addiction (1995, dir. Abel Ferrara)

After Bad Lieutenant, Abel Ferrara became the bad boy du jour and had so much pull, he could shoot a vampire film in black and white, so he did. Interesting that Ferrara chose vampires as the subject, given that every other film he ever made are about people sucking the blood and life from others and society (and conversely, our utter fascination with them). Lily Taylor as Catherine performs the vampire transformation impeccably, basically because Ferrara is smart enough to understand that the only effect you need is a great actress.

One of the great cutaway edits of the 90’s is when Catherine injects herself with blood in her bathroom for the first time, and the screen cuts to what looks like a home movie of Lily Taylor as an one year old running and laughing without a care in the world. This is what the first high is like, not a care in the world like a one year old. The cut alone is worth the price of the ticket.

The Addiction can be seen as a pean to lonliness- Ferrara maxes the Taxi Driver vibe wherein New York City, the densest populated city in America, but also the lonliest. The most intimate moments in the film come from blood extraction.

The Addiction also seems to be a left-handed anti-ode to Woody Allen’s black and white work. NYC directors mostly confine themselves to certain NYC castes- Allen wit the intelligensia, Baumbach with kvetching Jews, Ferrara with the gritty streets. In The Addiction, Ferrara’ s junkies leech the post-grad crowd, not the other way around. The final scene is every PhD students’ dream come true.

5. I Shot Andy Warhol (1996, dir. Mary Harron)

Before American Psycho, Mary Harron made I Shot Andy Warhol, a better movie (gasp!) based on the diaries of Valerie Solanas, a hapless, insane, overly intelligent woman who was sexually traumatized in her childhood, and who shoots Andy Warhol. Warhol died many years later, probably from Solanas’ bullets. I Shot uses a Citizen Kane framing device- but what I Shot gets right, even with its limited budget for a period piece, is the backdrop.

I Shot borrows a great deal from Midnight Cowboy, and would be remiss not to, but the canvas it paints of the time and place is unique, as is the perspective of the characters. Stephen Dorff takes a star turn as Factory acolite Candy Darling; Jared Harris is a wrecking ball as Andy Warhol, but the real star here is the screenplay (Mary Harron, Jeremiah Newton, Daniel Minahan ). Lone assassin stories are about isolation, but Lily Taylor”s Valerie has a social life and belongs somewhere, even if her people are street and throwaways.

Watching Warhol’s I, A Man featuring the actual Valerie Solanas, Taylor’s performance is seamless. Solanas was taken as seriously by Warhol as the other crack pots (ie “superstars”). As soon as Solanas is expelled from the Warhol Universe, she comes back and shoots him. I Shot is a fascinating well-made slice of a tumultuous era but what sets it apart is that it touches on how screwed up the rest of society is, especially sexually. Solanas worked as a prostitute and saw and felt first hand the kinks that the repressed sexual urge brings about, and how she and the poor are both the receptacle and janitor of what is under the surface.