Abbas Kiarostami is a familiar name to many people around the world. Since countless internet sites about him exist. He is considered by many as one of the best filmmakers of cinema. The filmmaker is a source of pride, because through his films, Kiarostami manages to present a new, refreshing image of Iran, a poetic outlook one can’t find in any other Iranian movie.

Like Kurosawa or Hitchcock, Kiarostami successfully creates a unique filmmaking style, the Kiarostami style, and in the last thirty years, his style has been a source of inspiration for many directors around the world. Kiarostami has been one of the pillars of cinema for many years, and whether anyone likes or dislikes his movies, no one can omit his name from the files of contemporary cinema. He is a director whose movies any cinema lover must watch attentively.

Thus, we compiled the list below, especially for those who have seen his movies and those who have not. We hope, after reading the entries, people are excited and inspired enough to watch his movies. If so, we suggest cinephiles watching them in chronological order; only in this way film fans will understand how the director’s style evolved, and how Kiarostami became Kiarostami.

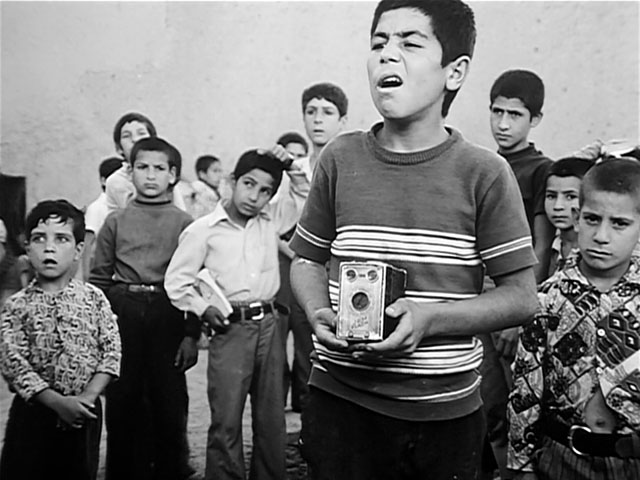

1. The Traveler (1974)

Kiarostami’s first feature film pays homage to neo-realism and Francois Truffaut’s 400 Blows (1959). The Traveler narrates the story of Qassem Julayi (Hassan Darabi), a wayward teenager who is in love with soccer, and his dream is to watch a match at the Amjadie stadium in Tehran. To accomplish his goal, he steals money and tries to sell a secondhand watch and a broken camera.

Pretending to take photos of his classmates, he also deceives and receives money from them. Toward the end, he sells his soccer ball and portable soccer goals. After a long day of making enough money, he goes to Tehran, and when he reaches the stadium, he is exhausted and falls asleep; when he wakes up, he discovers that the match is finished, and he is alone in the stadium.

Like any debut feature, the movie has some flaws. For instance, some scenes lack the necessary linking shots. In the scene when Qassem enters the classroom, for instance, the cameraman simply can’t place him in the frame, so the audience hears sound of a door then sees a sharp cut, and suddenly Qasem is behind his desk. Moreover, there is stylistic inconsistency; the director uses dramatic music in “exciting” scenes, which contrasts the film’s overall realistic/documentary style.

Nevertheless, these examples are all elements of the future “Kiarostami” style, which emphasizes realism; documentary and photography style; children as main characters; ignorant adults; thin plot line; and lonely protagonists. The Traveler may not be a perfect film, but after watching it, one will certainly know the director has a promising future.

Best Scene: The audience will never forget the whole sequence when Qassem deceives his classmates and pretends to take their picture.

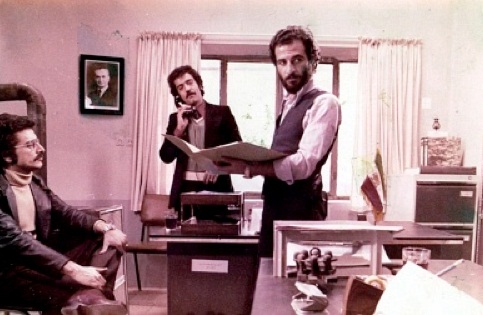

2. The Report (1977)

The Report chronicles the story of a man whose life unravels when he is suspended from his job. Thereafter, he quarrels with his wife, which causes him to make an important decision. Though realistic, The Report is more akin to Iranian rare modern dramas, such as The Brick and Mirror (Khesht va Ayeneh, 1965), directed by Ebrahim Golestan, as well as other than neo-realism films.

The Report focuses on how losing one’s job can affect a man’s behavior and lead to detrimental actions, like suicide. The man, in the final scene, makes the decision to leave his wife and child behind—not because he is a loser, but because he thinks his absence is the only way they may have a future.

The Report is the most interesting film of Kiarostami’s career. Though the film is a domestic melodrama, the main characters are not children. The actors are professional, the story line is well developed, and generally one will not notice any technical flaws. Movies that Kiarostami shot before and after The Report always consist of scenes that people assume the camera shakes or the viewer believes some connecting shots are missing.

Best Scene: The scene in which the man goes to a diner. While waiting for his sandwich, the man listens to drunken people discussing important, philosophical and existentialist issues.

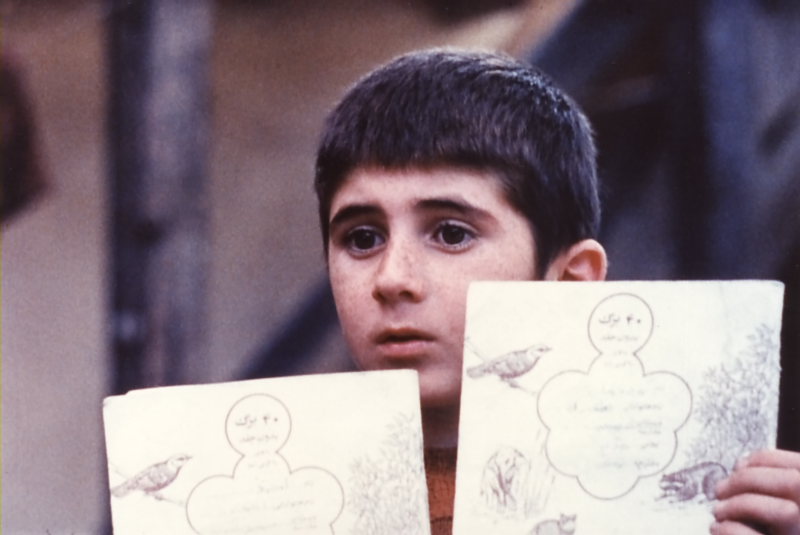

3. Where Is the Friend’s Home? (1987)

Where Is the Friend’s Home? is a pivotal point in Kiarostami’s career; it is a movie fans can call Kiarostamiesque. The film is the first safe destination of Kiarostami’s long journey to find a unique cinematic language that is both poetical and realistic. The film’s Iranian title derives from a poem by Sohrab Sepehri, an Iranian poet who is well-known for his love of nature and village life. Sepehri, who is also a painter, has greatly influenced Kiarostami’s films (In fact, Kiarostami’s photos contains Sepehri’s signature brush strokes.) Where Is the Friend’s Home? tackles the same morality questions that occupied Sepehri’s mind for years.

In this film, Kiarostami demonstrates the innocence of children and the morality of the villagers. In his long journey to find his classmate, Ahmed (Babek Ahmed Poor) understands how cruel and ignorant an adult’s world is. In the midst of the narrative, Kiarostami elevates some of his unique stylistic elements: balanced combination of documentary and fiction (docu-fiction), rare usage of music, and sparse plot line.

Where Is the Friend’s Home? is such an honest and crafty movie about being a young adult. Kiarostami was only forty-seven when he filmed this movie which earned him international recognition. During Locarno International Film Festival in 1989, the director was awarded the Bronze Leopard, the FIPRESCI prize (special mention), and Prize of the Ecumenical Jury. The film deservedly entered BFI list of the “50 films you should see by the age of 14.”

Best Scene: Almost the whole movie; the final scene is key when Ahmed returns his classmate’s notebook to show the child that Ahmed finished the friend’s homework.

4. Close-Up (1990)

Kiarostami has always been interested in documentaries and presenting reality in cinema. Therefore, Close-Up, which refers to a cinematic technique, is a movie about the power of cinema. It is not surprising to know that the director wrote the script of Close-Up based on a news story about a man who impersonates famous Iranian film director, Mohsen Makhmalbaf.

Another delicately balanced docu-fiction, the audience views both Makhmalbaf and the impersonator (Hamid Sabzian). As the movie moves forward, the audience learns that the impersonator doesn’t introduce himself as Makhmalbaf for financial reasons; he loves cinema and enjoys being called Makhmalbaf.

Close-Up helped increase Kiarostami’s international recognition—it was awarded Quebec Film Critics Award at the Montreal International Festival of New Cinema and Video and FIPRESCI Prize at the International Istanbul Film Festival. In the 2012 Sight & Sound poll, it was voted, by critics, as one of “The Top 50 Greatest Films of All Time.”

Best Scene: There is a long, memorable scene in which two main characters of the movie pass different streets on a motorcycle.

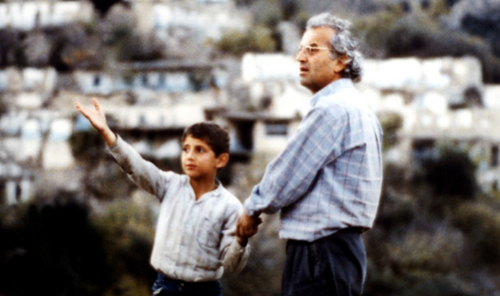

5. Life, and Nothing More… (1991)

The second part in the “Koker trilogy” (the first is Where Is the Friend’s Home?) narrates the story of a director in search of the actors in Where Is the Friend’s Home? after the disastrous Koker earthquake of 1990. Though the movie has a promising beginning, it is almost impossible to fathom that the film is based on one idea (life). That’s why the director’s journey at some points seems dull, and his encounters with different people who have lost loved ones are not dramatically fruitful.

However, in Life, and Nothing More… the audience isn’t searching for anything dramatic; if Close-Up (1990) is a fiction film based on real life events, Life, and Nothing More… is a documentary with few fictional elements. Thus, Life, and Nothing More… is a must watch for any Kiarostami fan, because the director uses, for the first time, “the dashboard camera” technique that matures in Taste of Cherry (1997) and elevates in Ten (2002).

This film introduced Kiarostami to Cannes Film Festival (and the director’s second home, France); it was presented in the Un Certain Regard section of the ceremony, and the critics lauded it.

There are many scenes in Life, and Nothing More…, for instance, the scene that reveals only the highway while the audience hears non-diegetic dialogue.