6. Through the Olive Trees (1994)

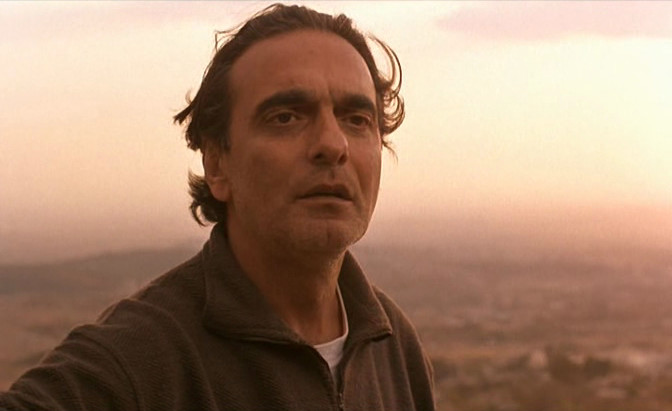

The last part of the “Koker” trilogy, and one of Kiarostami’s best films to date, is Through the Olive Trees. This time, the film chronicles a director named Mohamad Ali Keshavarz—a kind, unforgettable face—who happens to be shooting a film, “Life, and Nothing More….”.

Through the Olive Trees is a very simple, light-hearted romance movie, but if one reads between the “scenes”, he or she will realize that like Close-Up (1990), Through the Olive Trees is another film about the power of cinema. Hossein, a local actor (played by Hossein Rezai), loves Tahere (played by Tahere Ladanian), but she rejects him. During their on-screen “performance,” Hossein uses this opportunity to propose marriage to Tahere and convince her that he is a suitable husband.

However, in order for Hossein to follow through, the director, Mohamad, supports Hossein’s proposal. For example, Mohamad asks Tahere to call Hossein by his name, and for Hossein to follow Tahere among olive trees and talks to him.

Through the Olive Trees is a masterful work that reveals that Kiarostami has reached the pinnacle of his career and also the zenith of his fiction/documentary style. (When watching the film, people should remember to search for Iranian director Jafar Panahi—in the blue suit shirt and jeans—who plays the directors’ assistant!) Moreover, this film competed for the Palme d’Or in Cannes and affirmed Kiarostami’s position as one the most talented contemporary filmmakers of all time.

Unlike the rest of Koker trilogy, the film is absent of a soundtrack, except some music during the opening and ending titles. The final scene, which is one of the most memorable cinematic scenes of the 1990’s, confirms that Kiarostami knows how to utilize his cinematic painting experiences, as well as transform a melodramatic scene into a poetic one.

Best Scene: The memorable final scene in which Hossein follows Tahere “through the olive trees” to propose to her. In an extreme long shot, Hossein follows and talks to Tahere, who finally turns, looks at, and says something to Hossein that compels Hossein run back. The audience must decide, at this point, what Tahere’s choice is. . .

7. Taste of Cherry (1997)

Kiarostami’s masterpiece is the story of a man named Badii (Homayoun Ershadi), who looks for someone to bury him when he is dead. The movie is simplistic, yet complex, and open to various interpretations. It is the first real minimal movie of Kiarostami’s—a critical point in his career that awarded him “Palme d’Or” in Cannes, but also divided critics: Roger Ebert hated it, while Jonathan Rosenbaum hailed it.

A vehicle—a visual motif Kiarostami started using since Life, and Nothing More…, as well as the primary location of this movie—is an actual “place” (even character) in this film. The vehicle as the primary location also resembles a graveyard, which symbolizes Badii and Kiarostami’s outlook on life and death.

Though Taste of Cherry is a bleak movie and story of a man on the verge of suicide, it has a hidden comical layer, which only an Iranian audience may understand. Nevertheless, this comical tone (something rare in Kiarostami movies) is created through the witty and smart discourse of Badii’s passengers. It is through these dialogues that Kiarostami presents his philosophy of life: depressing and gloomy while also pleasurable and full of happiness. The audience understands that Badii’s decision is going to change, and while he is lying in the grave, he hopes he will not die.

Kiarostami deliberately didn’t use any music in this movie, except for the final scene when the audience hears a non-diegetic trumpet piece by Louis Armstrong, which is a tune that sings about death being just around the corner, and it accentuates the double meaning of the film’s ending. Jonathan Rosenbaum— who wrote about the “the first English Study of an Iranian director” (University of Illinois Press) stated thus about Taste of Cherry:

“The most important thing about the joyful finale is that… it does invite us into the laboratory from which the film sprang and places us on an equal footing with the filmmaker, yet it does this in a spirit of collective euphoria, suddenly liberating us from the oppressive solitude and darkness of Badii alone in his grave. Shifting to the soldiers reminds us of the happiest part of Badii’s life, and a tree in full bloom reminds us of the Turkish taxidermist’s epiphany — though the soldiers also signify the wars that made both the Kurdish soldier and the Afghan seminarian refugees, and a tree is where the Turk almost hung himself. Kiarostami is representing life in all its rich complexity.”

Rosenbaum is right: the ending reminds the audience of the final scene in Holy Mountain (Alejandro Jodorowski), as Taste of Cherry is both depressing and cheerful, and it’s the audience, as well his philosophy to decide if life is a cul-de-sac or road to take and enjoy the taste of cherry while walking on it.

8. The Wind Will Carry Us (1999)

The follow-up film to Taste of Cherry (1997) is The Wind Will Carry Us, which also addresses life and death. It is not surprising that death obsessively consumed Kiarostami’s mind ever since he was fifty-nine (see The Wind Will Carry Us).

The title stems from a poem, written by the most important female poet of Iran, Forough Farrokhzadl, the film references Omar Khayyam’s poems as well. Khayyam’s poems are usually about seizing the moment; the film’s references to Khayyam’s pieces create a comedic effect for the film, especially when the journalists are waiting for the old woman’s death!

The movie was very successful in festivals and among critics—at the Venice Film Festival, the movie was nominated for the Golden Lion and won the Grand Special Jury Prize (Silver Lion), the FIPRESCI Prize, and the CinemAvvenire award.

Actor J. Hoberman explains the film exquisitely: “It’s part of the movie’s formal brilliance that, suddenly, during its final 10 minutes, too much seems to be happening. The Wind Will Carry Us is a film about nothing and everything—life, death, the quality of light on dusty hills.”

9. Ten (2002)

In the 2000’s, Kiarostami began making experimental movies—Ten is the first and Shirin (2008) is the last. Ten is Kiarostami’s most accomplished experimental film, however, as it is his first movie about women, as well as his most fruitful effort in eliminating the director during the course of filmmaking. He tried restricting his director’s role as much as possible, using very little camera movements, and allowing the actors to improvise.

Thus, the entire film is shot with a dashboard camera in which the camera focalizes on these characters—the director uses the “point-of-view” shot from the character’s perspective: the driver (a divorced woman) or her passengers (her son, other women, etc.)

The improvisation technique Kiarostami uses also provides the audience with the notion that the director didn’t have a script. However, the dialogue between the women is so unified, which shows that Kiarostami plays an important role in directing these semi-improvised conversations. Ten is Kiarostami’s first movie about different type of women, and today he proudly continues to make these types of films.

Ten is also considered one of Kiarostami’s most successful films. It was nominated for the Palme d’Or at the 2002 Cannes Film Festival and ranks number 447 on the 2008 list of the “500 greatest movies of all time,” which was compiled by Empire Magazine. In 2010, Empire Magazine ranked the film No. 47 in its “The 100 Best Films of World Cinema.” The French film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma ranked the film 10th place in its list of Best films of the decade: 2000-2009.

Best Scene: All the scenes in which the driver’s son is present. He talks so passionately and arrogantly—his speech is unforgettable.

10. Certified Copy (2010)

Kiarostami’s first film shot entirely outside Iran premiered renowned French actress Juliette Binoche, who is long-time friends Kiarostami; though Binoche played a tiny role in Shirin (2008), Certified Copy is Kiarostami’s first feature length film in which she stars. Certified Copy is another experimental project for Kiarostami wherein he creates a film that is closer to the “true” definition of cinema.

This film—though made outside Iran and is available in other languages besides Persian (French, English and Italian) — is Kiarostamiesque in many ways. The movie is about how love can be genuine or fake, and it demonstrates that Kiarostami never forgets his own style—it recounts the adventures of the characters in a single day; a vehicle is the primary location in this film; and the cinematography trumps the non-diegetic dialogue of the characters.

Kiarostami illustrates his skillful filmic discourse—realistic dialogue that resembles everyday speech, but contains deeper meanings and layers. The film premiered at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival where Binoche won the Best Actress Award for her performance.

Best Scene: The final scene in which the audience thinks they know the woman so well, but suddenly realize that she doesn’t even have a name!

Author Bio: Hossein Eidizadeh is a film critic and cinephile from Iran. He has interviewed David Lynch, Margareta von Trotta, Barbara Sukowa and many others. He writes film posts on his blog closeupkino.blogspot.com.