5. Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (Karel Reisz, 1960)

Set in the city of Nottingham, another industrial spot, is another directorial debut by one of the pioneer greats, Karel Reisz. Reisz was Czech and Jewish, and one of 669 Holocaust victims rescued and brought to England by Nicholas Winton. Albert Finney, an acting legend of the movement, makes his acting debut in this film.

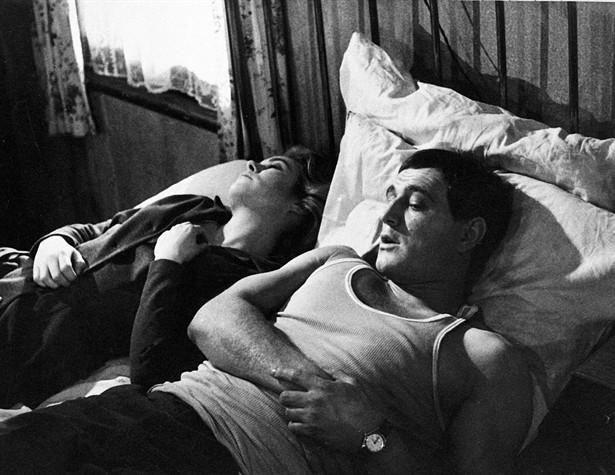

Produced by the great Tony Richardson, Saturday Night and Saturday Morning about Arthur (Albert Finney) as a young factory worker, who juggles between two relationships with two females, one of whom is already married and pregnant with his child.

Whilst one reads this list, he or she will naturally notice another common theme—besides unmarried pregnant women and interracial couples—within the New Wave, which is infidelity of married couples—couples who commit adultery and complicate matters. However, these societal components are realistically common, and the films of the New Wave movement characterizes the truth of the “real world.”

If people in the “real world” actually argue, drink, and commit adultery then why can’t the cinema do the same? Returning to Lindsay Anderson’s hopes of turning cinema away from the “snobbish, anti-intelligent, and emotionally inhibited” world it became, one will surmise that films like Saturday Night and Sunday Morning proves that filmmakers like Anderson and Reisz have a point to prove.

This film received a surprising box office success and received three BAFTA award wins, including Best British Film and Most Promising Newcomer (for Finney) to Leading Film Roles.

4. The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (Tony Richardson, 1962)

By 1962, the New Wave had proved successful to audiences worldwide, and British cinema had gained the respect from producers of the high quality of films outside of British New Wave (i.e. such as the James Bond franchise). Behind the success of these classic films are the (now) highly respected filmmakers, including that of the pioneer Tony Richardson. His next project after A Taste of Honey was The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner adapted from the short story by Alan Sillitoe.

Colin (performed by another New Wave legend, Tom Courtenay) has recently been incarcerated for robbery. Within time, his superb athletic skills in long-distance running earns him respect in the institution. Of course his life of privilege doesn’t feel as great as it seems, especially since he is the school governor’s (Michael Redgrave) “favorite.”

Another theme associated with the movement is the rebellion against authority—in this case, Colin’s defiant character toward the Governor. This film, at the time of its release, likely proved important to the British youth of the day. As the New Wave focuses on social realism, the film examines the feelings of Colin’s character, and of course as the title suggests, his loneliness.

Of course the New Wave also focuses on the gritty lives of the unfortunate, such as isolation. The dry and angst nature of the character in this film reveals the perfect example of the “angry youth” or “angry young men” syndrome to which the New Wave attributes.

Like Albert Finney two years before him, Tom Courtenay won the BAFTA film award for Most Promising Newcomer to Leading Film Roles. The BAFTA’s couldn’t have been more accurate, for these two young actors transformed into acting legends.

3. This Sporting Life (Lindsay Anderson, 1964)

From one pioneering icon (Richardson) to another, and maintaining the topic of sports, is Lindsay Anderson, who directs This Sporting Life. Frank (Richard Harris) is the macho and ambitious rugby league star in Wakefield, Yorkshire. Like the themes that the New Wave carries—ambition and dreams—Frank can only dream big.

The film’s tone, however, resonates well with today’s society of Northern England, class division, ego, sex, etc. It’s within that tone that the film remains highly influential today.

Frank’s character falls for his widowed land lady; unfortunately, Frank’s romantic life isn’t as great as his sport’s life. The film is not just realistic and harsh, but vulnerable and bitter. Just like the “angry young men” that the New Wave had invented, Frank is also angry; he is aggressive toward his opponents on the rugby pitch, and they become his enemies.

This aggression is carried from the field to his home, where he and his land lady Margaret (Rachel Roberts) struggle to form a steady relationship. Some consider this film as the last of the great films of the New Wave.

Although the film was financially disappointing, it was received successful recognition at Awards Ceremonies—two Oscar nominations for Harris and Roberts; two nominations at the Golden Globes; five nominations at the BAFTA’s; and two nominations at Cannes of that year, including the Palme d’Or.

2. If….(Lindsay Anderson, 1968)

In 1968 came a sudden shock to the New Wave. A film poster read now world renowned tagline: “Which side will you be on?” Another classic by Lindsay Anderson, starring Malcolm McDowell in one of his earliest of roles, is If…. Rebellious Mick Travis (Malcolm McDowell) attends a strict all-boys boarding school where, after tiring from the authoritative regime, forms a revolution within the school. The film contributes to the controversial time period, as it parallels the violence of 1960s.

Critics have mentioned that this film stylistically and structurally prevails over the rest of the New Wave films. As previously mentioned, a common theme in these films is class differences. Instead of the usual economic class division concept, this film approaches the segregation of class, in the educational sense—between different age groups—and individuals who have power and authority.

The British New Wave certainly was revolutionary in mocking authority, and this film had an interesting blend of satire and surrealism. The satire works well because it mocks the private school system, an institution usually associated with the upper classes, and the New Wave blatantly represented these themes associated with the ruling class.

The film was extremely successful, winning the Palme d’Or for Anderson at Cannes that year. The film also received two BAFTA Film nominations and a nomination at the Golden Globes.

After watching the film, director Stanley Kubrick knew immediately to cast Malcolm McDowell in the legendary film, A Clockwork Orange (1971); however, by then, the New Wave was officially over. The character Mick Travis continued on in two more films directed by Anderson: O Lucky Man! (1973) and Britanna Hospital (1982).

1.Kes (Ken Loach, 1969)

As the sixties ended, so did British New Wave. Thus, Kes is regarded as one of the greatest British movies of all time. The young David Bradley plays Billy Casper, a fifteen-year old boy who is often the victim of bullies. Just like the The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, the young can be seen as alone and sad, whilst the older men are the obvious “angry young men.”

Billy, a working-class citizen from Barnsley, Yorkshire, befriends a pet kestrel with which he spends almost all of his free time. The plot seems simple, almost boring; why did it receive critical acclaim and recognition? Is it because of social realism and how the youth relates to it depending on their circumstances?

Maybe the film’s low budget and cinema vérité style, which influenced independent filmmakers, is the reason? How about the Italian films of the 1940s? Or the mockery and satire of capitalism and the authority in the education system—both common enemies in the principles of the New Wave?

Perhaps these ideas all contribute to the film and brand this film a little different than the average fictional piece. As the New Wave closed forever, the film went out in style. It’s a bitter tale, but it’s become something so loved and admired, even 45 years later.

Unlike the previous two films, Kes didn’t have a wide international hit, but it did make a decent profit. It was nominated for six BAFTA Film awards and won two—one for the young David Bradley as Most Promising Newcomer to Leading Film Roles.

Notable omissions of the British New Wave include A Kind of Loving (1962); The Servant (1963); Tiger Bay (1959); Hell is a City (1960); The Entertainer (1960); Tom Jones; (1963) The Bill Douglas trilogy (1972-78); and A Hard Day’s Night (1964).

Author Bio: Christopher is a self confessed cinephile, from North Staffordshire, England. He works as a administration clerk, but also makes short films too and one day hopes to become a professional filmmaker.