The long and arduous history of Spanish cinema finds its roots primarily in the Francoist regime. With Franco’s forty-year stronghold on Spanish culture, Spain’s film industry took new and interesting forms. Outside influence was seen as dangerous, and films were dubbed into Castilian and severely cut to remove any controversial elements (in the case of Mogambo, an adulterous plot line was censored by turning two characters into siblings).

The waning years of Franco’s regime marked the high points of the careers of some of the most subversive directors, such as Victor Erice, Vicente Aranda, and Carlos Saura. Metaphor was their mode of attack, and the plots and characters were used as allegories for the contemporaneous state of Spanish politics.

Franco’s death lead to a cultural upheaval called La Movida. Indulgence and pleasure was the driving force of this cultural movement, creating one of the leading figures of Spanish cinema: Pedro Almodóvar. Almodóvar’s transgressive comedies and colorful melodramas created a new and unique image of Spanish films, challenging notions of what Spanish culture was/is/could be. Along with Almodóvar came filmmakers like Fernando Trueba, Bigas Luna, and Alejandro Amenábar, ushering in a new era of Spanish cinema.

Spanish cinema’s long history is what makes these movies all the more powerful. From repression to aggression to transgression, the fifteen films on this list represent some of the masterpieces of Spanish cinema.

15. Tesis (Dir. Alejandro Amenábar, 1996)

Blood and violence are an integral part of Spanish cultural (look at the reverence for the figure of the Matador), and it becomes an integral part of Alejandro Amenábar’s directorial debut, Tesis (Thesis).

The film follows Angela (Ana Torrent, who will be appearing frequently throughout this list), a college student who is writing about snuff films for her thesis. When people around her begin dying, Angela becomes involved in an investigation that may lead to her starring in someone’s snuff film.

It is a provocative look at the blur between media/cultural representations of violence and real acts of violence. Since it is specific to Spanish culture, Thesis questions how Spain’s culture of blood and violence will affect younger generations.

14. Mar adentro (Dir. Alejandro Amenábar, 2004)

The inclusion of Mar adentro (The Sea Inside) on this list is an exercise in looking at the way in which Spain crafts its image. This is not to deride the film in any way.

The story of Ramon Sampedro’s (Javier Bardem) 28-year battle for euthanasia is beautifully made, but also is an “Awards Film.” It is meant to cater to a broader audience, rather than appealing to a specific niche market.

In the same year, Almodovar released his controversial La mala educación (Bad Education), which was overlooked to represent Spain for the Academy Award for Foreign Language Film. The Sea Inside was chosen instead, going on to represent Spain and eventually win the Oscar.

13. Cambio de sexo (Dir. Vicente Aranda, 1977)

Filmed after the death of Franco, Vicente Aranda’s Cambio de sexo (Sex Change) constructs a political allegory for the changing image of Spain.

A young José Maria (Victoria Abril) escapes the clutches of his chauvinist father and conservative town, running away to a cabaret that features the infamous transsexual, Bibi Andersen (played by herself). José Maria becomes Maria José, discovering her true identity in the liberal town.

With the death of Franco, Spain became more liberated and open to a globalized community. Like José Maria, Spain constructed a new identity for itself outside of its repressed roots.

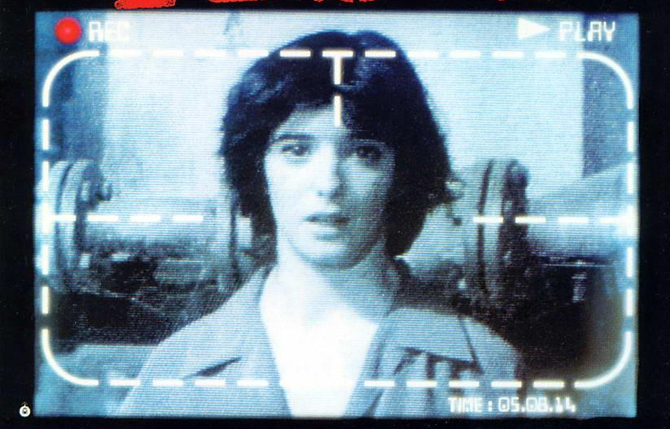

12. [REC] (Dirs. Jaume Balagueró and Paco Plaza, 2007)

[REC] is a master class in horror, creating suspense out of claustrophobia, uncertainty, and cultural specificity.

Angela Vidal is a television reporter who works on “While Your Were Sleeping,” a news segment that follows people who work at night. One night, she accompanies her subjects (firefighters) to an apartment complex where a seemingly rabid woman is running amok. Unbeknownst to the firefighters and the tenants, a virus is spreading amongst the complex, contaminating anyone who is bitten or scratched by an infected person.

Immediately after its release, Hollywood remade the film into Quarantine, which failed on all cylinders. [REC] works because of its Spanish specificity, even drawing from religious roots to blame the disease on (Spoiler Alert) demonic possession. Though the film isn’t as political as the other films listed here, it is still great representation of Spain’s ability to build and develop generic conventions.

11. Todo sobre mi madre (Dir. Pedro Almodóvar, 1999)

Almodóvar’s story about Manuela (Cecilia Roth), a nurse returning to Barcelona after the death of her son, is as much a celebration of Spanish culture as it is an examination (in the literal and metaphorical sense) of transplantation. Manuela’s trip from Madrid to Barcelona begins with a rebirth through a train tunnel. From there, we get an overview of Barcelona, a look at Gaudi’s architecture, and a journey through the prostitution rings.

The film looks at how Spaniards preserve their cultural heritage and how they transplant new influences (like Truman Capote, All About Eve, and A Streetcar Named Desire) into their daily lives.

10. Ana y los lobos (Dir. Carlos Saura, 1973)

In the history of Spanish cinema, Carlos Saura definitely made the most radical and politically charged films.

Saura’s Ana y los lobos (Ana and the Wolves) is one of his more brutal films, looking at how a foreign governess named Ana (Geraldine Chaplin) assimilates into the crumbling mansion of a Spanish matriarch and her three adult sons. The family symbolizes the Francoist regime, with each son’s obsession (sex, military, religion) representing the various factions operating Francoist Spain.

The climatic scene in which Ana is (Spoiler Alert) raped, scalped, and murdered – at the command of the matriarch – provides a powerful attack against the state of Spanish politics. The ending reveals Spain cannot transcend the dictatorial powers of the regime without the death of the person in charge, and Saura would explore this theme in the sequel (of sorts), Mama cumple 100 años.

9. Tristana (Dir. Luis Buñuel, 1970)

Buñuel’s second return to Spain is, as expected, controversial. It examines the tumultuous May-December romance between Tristana (Catherine Deneuve) and Don Lupe (Fernando Rey). As the years pass, the innocent Tristana becomes more bitter and resentful, becoming more of a compliment to Don Lupe’s selfish nature.

It is another film that attacks religion and the bourgeoisie, two institutions that Buñuel had been fighting against for years. The film represented Spain in the category of Foreign Language Film at the Academy Awards, but would unfortunately lose.