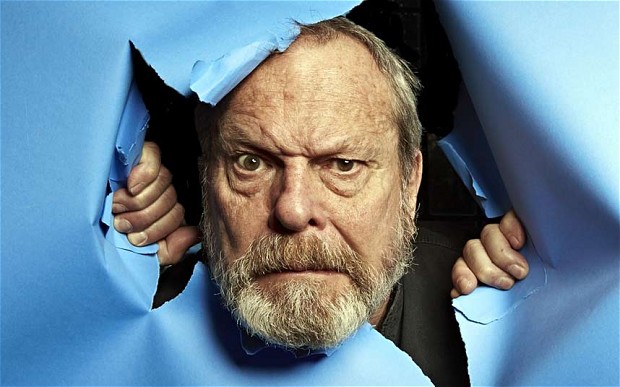

11. Terry Gilliam and the struggle between reality and imagination

Starting in Monty Python’s Flying Circus, Gilliam made himself notice with his anarchic animation where he would recycle old photographs, postcards and magazines, among other things, to make fun of the parody of the conventionalities and expectations of people, much in line with the humor of the Pythons. Gilliam found himself in the director’s chair for the first time with Monty Python and the Holy Grail, but soon the rest of the group felt Gilliam’s obsession for professionalism hindered their comedic spontaneity. It wouldn’t be until Time Bandits that Gilliam would refine a solid voice.

Time Bandits, along with Brazil and The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, are thematically a trilogy that follows the struggle of imagination in different ages (childhood, adulthood and old age, respectively) but said struggle is something Gilliam never really abandoned. His heroes tend to be outsiders, dreamers and maniacs with a foot on reality and another one somewhere else, somewhere better. Yet, despite their relative grasp of reality due to drug abuse, insanity, imagination or actually being from other time and place, his heroes manage to have a better understanding of the humdrum lives of drab stupidity outside their imaginary realms.

12. Paul Thomas Anderson and the consequences of success

Paul Thomas Anderson took cinema by surprise at the age of 27 with 1997’s Boogie Nights, an epic about the pleasure and decadence of the San Fernando Valley porn industry in the 70’s and 80’s. He earned a reputation of a prodigy that so far hasn’t been tarnished with Magnolia, Punch-Drunk Love, There Will Be Blood and The Master offering deep, meditative studies about people, alienation and success.

Most of Anderson’s characters yearn for some fulfilling meaning in their life, but reaching their goals doesn’t make the angst go away. Instead, it makes their aching more palpable. Dirk Diggler and the rest of porn actors in Boogie Nights, Daniel Plainview in There Will Be Blood and Freddy Quell in The Master do what they know for reaching fame, money and internal peace, respectively. Yet, their goals become prisons and out of the three, only the latter one finds a way to escape.

13. Guillermo Del Toro and clockwork machinery

Inspired by fairytales, comic books and horror stories, Mexico’s Guillermo Del Toro has made widely successful blockbusters and smaller and more personal projects adapting his own peculiar vision flawlessly. A common thread in his projects, among the themes of religious paraphernalia and insectoid monstrosities are the mechanical imagery of machinery spread as forces beyond mere humanity.

In his first featured film, Chronos, the action centers on a beetle-like gizmo capable of giving eternal life, but cursing those who use it. Karl Kroenen, the main villain of Hellboy, is a Nazi scientist reanimated by a mix of black magic and Dieselpunk-like mechanics, not unlike Johann Krauss from Hell Boy II: The Golden Army, an ectoplasm being contained in a mechanical suit. His love with clock imagery sometimes is far more abstract.

In Pan’s Labyrinth, for example, Capitán Vidal is not only obsessed with his father’s pocket watch but also has his headquarters in an abandoned windmill and of course, the giant human-piloted cyborgs in Pacific Rim go without saying.

14. Sofia Coppola and the alienation of comfort

The life of Sofia Coppola has always been bounded by cinema, whether she liked or not. Daughter of famed New Hollywood director Francis Ford Coppola, she played the son of Michael Corleone during the famous baptism scene in The Godfather. Unfortunately, she first gained attention for her much-criticized part in The Godfather III, where denounces of nepotism abound. Despite this, she managed to rise above her father’s shadow and earned a good reputation for memorable films like The Virgin Suicides, Lost in Translation, and Marie Antoinette.

Perhaps inspired by her Hollywood upbringing, the movies of Coppola typically possess the same preoccupations: people, usually women, who despite having everything they could virtually wish for, feel trapped by their own privilege. Long silent existential crisis are frequent, usually trying to find someone or something outside their gilded cage that can save them or, if salvation is inevitable as it usually happens to them, they can at least lie themselves for a few golden moments.

15. Guy Maddin and old-time Canada

Nowadays, not many film directors advocate such a wildly radical cinematic movement as surrealism, but Guy Maddin is not like many filmmakers. Born in Winnipeg, Canada, Maddin has made himself known thanks to his experimental productions, generally using techniques and styles from the 20’s and 30’s. For example, Brand upon the Brain!, is not only done in black and white film with rudimentary vaguely historical setting, but also without counting the occasional “noise” and the narration of Monica Bellucci, the film is completely silent.

But another important element for Maddin is his Canadian identity, creating a make-believe dream-like old-time Canada. Tales from Gimli Hospital, his first featured films, dealt with a grandmother telling tall tales to two brothers about the Icelandic inhabitants of Gimli, Manitoba in a faraway past. The same can be seen in My Winnipeg, where he joins several historical happenings of the city with his own family history without discerning truth from fiction.

Yet another fictional version of Winnipeg appears in The Saddest Music in the World, nominally set in 1933 and again, a fictional version of Maddin appears living in a remote island orphanage, blurring again the past, the present, the reality, the fictional and, somehow, Canada.

Author Bio: J.E. González is a writer and journalist from Venezuela. With a degree in Social Communications, he has a passion for world culture and narrative arts. You can follow him on Twitter at @maxmordon.