14. Down to the Bone (2005)

A realist movie if ever there was one. This story of a Irene (Vera Farmiga), a woman who struggles to juggle motherhood, drug addiction, and an affair with fellow addict Bob (Hugh Dillon) attempts no glamour or Hollywood sentiment; it is quintessentially indie. The American flag flies over gloomy urban slums as a stark plot unfolds which pulls no punches.

Irene packs bags at a grocery store, she drives home, drives to score, and has occasional romantic encounters without any hint of the burgeoning glamour that we are accustomed to. Only the family’s pet snake provides any hint of the exotic.

Like the snake slowly consuming its prey, one gets the idea that the characters are very much consumed by, and trapped in this life of monotony. However, the hope and beating heart of the piece lives and breathes in Vera Farmiga. Her dignity and determination keeps the audience from drowning in the mirk, instead we identify and are somewhat edified.

In the end, Irene chooses to protect herself, whatever the cost; one can relate. This strikingly shot, tensely crafted work of indie realism comes highly regarded by critics.

13. Birth (2004)

Featuring subject matter as controversial as any film and initially derided by the vanguard of the world’s critics, Birth nonetheless is the work of consummate craftsman in Jonathan Glazier and a stellar lead performance from Nicole Kidman. Yes, the critical reevaluation of this piece is well underway, thanks to its rich fairytale aesthetic and searing humanity.

Roger Ebert, one of the film’s admirers, likened the film to Rosemary’s Baby. This is certainly evident in scenes in which a snow capped New York looks like something out of fantasy, and through the bewitched nature of Kidman’s Anna. But, perhaps, the film is even better seen as a hunting elegy on loss, or even as the 2000s’ oddest break-up movie.

Many viewers were unable to get past the pedophilic elements of the film’s narrative. True, seeing Kidman in a bath tub with a ten year old boy claiming to be her husband reincarnated will provoke too much knee-jerk outrage for many; ditto with the notorious kiss. But, alas, the point is not to tell a tale a pedophilia, of which there is none explicitly or implicitly.

This is a tale of loss, of sadness following the death of a loved on and how we search for answers. The journey that this film takes is rewarding, and worth the shock.

12. House of Sand and Fog (2003)

A property dispute turns fatal in this film which is as grim and irky as the city encapsulating fog that the film’s cinematography so gamely depicts.

Aside from the occasionally derided shots of Jennifer Connelly’s Kathy on a beachside pier, criticised for their similarity to similar moments in the earlier film Requiem for a Dream, House of Sand and Fog was rather lauded by critics. The film explores two characters from vastly different backgrounds who, nonetheless, are equally consumed by perversions of the American Dream, destroyed by the city that they thought could be called home.

The movie belongs to Connelly and Ben Kingsley. Kingsley excels as Massoud, a general in his native Iran who nonetheless must suffer the indignity of a manual labour job in the United States in order to make his dream of life in America come true for his wife and son. Kathy (Jennifer Connelly) is a perturbingly desperate character.

Homeless after Massoud’s family takes her house, we witness her at the dismal edge of the American spectrum, in love with a married man and fighting addiction, constantly needing support of some kind after a gripping scene in which she injures her foot. Neither character shall emerge for the better, we are keenly aware of this from the onset. This is searing, thought provoking cinema.

11. The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007)

A lyrical and deliberately paced film, this film encouraged some criticism but much cult devotion. Aesthetically beautiful and epic, Brad Pitt’s Jesse James is presented in this film as poetically as any gunslinger, and also with a sadness that will resonate with the viewer long afterwards.

Told through omniscient narration, we witness the deterioration of Jesse James, voyeuristically witnessed through the eyes of both his biggest fan and his potential murderer. The exhaustion of Brad Pitt’s Jesse and the desperation of Casey Affleck’s Robert Ford allow the film to resonate ominously long before any bullets fly. In fact, it is the waiting for violence to occur that this western, like the great Spaghetti Westerns of old, concerns itself with.

The film took two years to find distribution after it was finished. That, along with certain misreadings of the film may have led to slightly less than unanimous acclaim for the film. The film has been interpreted as a critique of celebrity culture, with Robert Ford pining for Jesse’s acceptance as he has grown up hearing tales of his legend. A dinner table scene in which Jesse informs Ford that most of the tales are false is particularly telling.

However, the film is better described as a cautionary tale against assigning myth to mortals. Jesse is the product of a dying breed. He is introduced as a Confederate freedom fighter, though the war is already lost. His insecurities are as evident as Roberts, his fears too. This makes the film’s conclusion all the more mythic, an irony which may not be lost on the viewer.

10. Punch-Drunk Love (2002)

When Paul Thomas Anderson announced at Cannes that his next film would be a romantic comedy with Adam Sandler, the announcement was met with laughter from a crowd that assumed Anderson to be speaking in jest. Yet, Anderson had a curiosity for both Sandler and the romantic comedy that he could not resist.

So, the film transpired, and the result was extraordinary indeed. Punch Drunk Love is deceptively breezy. Yes, the film is a romantic comedy. However, its gentle pace, dreamy music, its lead actor, and the film’s premise deceptively hides neurosis, sadness, and even violence buried just under the surface.

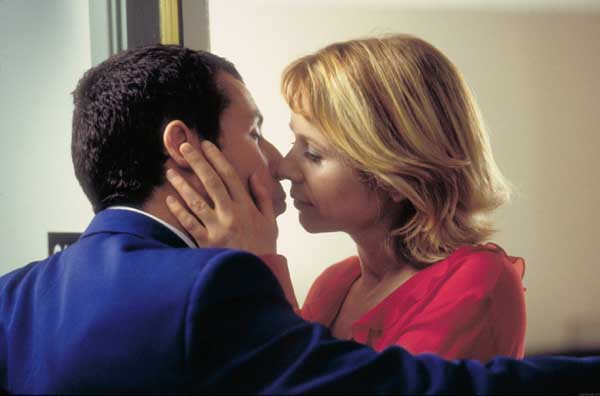

Barry Egan is a thirty-something misfit with seven sisters and no girlfriend. He runs his own plunger manufacture business. It is a conventional premise, but from the onset things get unfamiliar. There are phone sex lines, harmoniums, blackmail threats, and room trashings. To see these odd events, all told through the innocence of Barry and his love interest Lena (Emily Watson) is striking.

One particular scene involves Barry running and leaping to escape some thugs, all told through the gentle long shots associated with the romance genre. Striking too is Barry’s bright blue suit in contrast to Lena’s red dress, casting them both as outcasts. These are outcasts you can learn to care for, resulting in Adam Sandler’s brief moment in the critical favor.

9. Broken Flowers (2005)

An ageing Don Juan receives a pink letter informing him that he is a father. But from who? And who is the son? This is one of the strangest movies ever to be played dead straight. It is just as well, then, that director Jim Jarmusch cast the deadpan comedy guru Bill Murray, fresh off a career revival, as his leading man. What follows is a detective story that feels more like a window into the wreckage of an old rogue’s past.

Thankfully, the characters are played straight as Murray’s Don Johnson. The promiscuous ex and her voyeuristic daughter, the jealous lesbian lover, the loveless upper class marriage, the irate biker chick, the characters that Don meets on his journey of investigation into his past become apt incites into various break-ups of Don’s, not to mention the human condition in general.

Of course, there are plenty of signs of Jarmusch’s odd take on humanity. The sleuth-obsessed neighbour of Don makes him an odd mix cd to play on his voyage, one which periodically keeps the tone of the film somewhat surreal. As does Don’s inexplicable decision to wear only Adidas training attire. But, as witnessed by a graveside visit by Don to a perished ex, the humanity of this film tends to admirably overpower any indie contrivement. This comes as good news in a film that prides questions over answers.

8. The Royal Tenenbaums (2001)

The tagline “Family is not a word, it’s a sentence” is an apt one for the film that cemented Wes Anderson as a fixture of indie cinema.

When a family including a disdainful old sage Royal (Gene Hackman), his long-suffering ex-wife Etheline (Anjelica Huston), droll diva Margot (Gwyneth Paltrow), adversarial entrepreneur Chas, and troubled former tennis star Richie (Luke Wilson), find themselves under the same roof for the first time in years following the announcement that Royal is dying, tension and absurdity mounts. Of course, as does a sensational vintage soundtrack.

As always with Anderson, there is much colour and surreal character staging. The script, too, is wild and boisterous as lines such as “you want to talk jive, I’ll talk jive with ya” are given hysterical weight.

But, family runs deep, and so do the tender moments. Richie’s brush with suicide is followed by an unforgettable scene in a tent with Margot, the final moments between Royal and Chas are worth the time alone. As the family ensemble walk out of frame together at the end of the film, we feel like we have taken quite the journey with them.