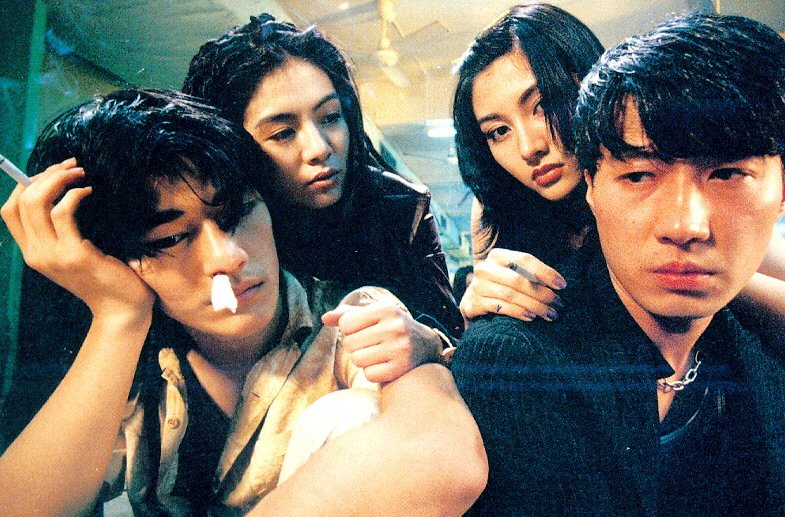

4. Chungking Express (1994)

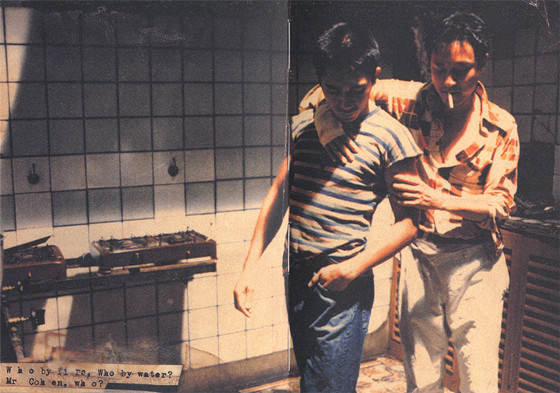

Filmed during a two-month break from editing Ashes, Chungking Express deals with similar themes in a relatively more lighthearted, contemporary story. The film is divide into two parts, each concerning a lovesick policeman who is getting over a breakup. Each story has little to do with the other except for a brief intersection where the first ends and the second begins. The film juxtaposes a densely populated Hong Kong with the isolated inner worlds of characters’ memories and nostalgia.

This paradox materializes through Wong’s frenetic handheld camera, deeply saturated florescent light, a restless editing pace, and a contemporary-pop soundtrack. Hong Kong is rendered in all of its modernity, while at the same time externalizing the emotional confusion of characters. Here, the director once again draws attention to the underlying connection between people and their time and place, depicting the private lives and relationships of individuals as results of their culture.

In fact, the English title “Chungking Express” is a collision of the films settings, the Chungking Mansions and Midnight Express food stall, and all of their physical and symbolic import.

If the first story is about unconsummated love, then the second is about unmaterialized love. In the second story, Faye, the snack shop girl, longs for Cop 663 from afar, even as he dwells on his ex-girlfriend. While He Qiwu and the drug smuggler are unrelated until they are brought together by their shared misfortune near the end of the first story, 663 and Faye are in constant physical proximity.

In scenes where 663 waits in the snack shop, Faye dances around to her favorite music and steals glances at him; when he catches her they share only a few words here and there. During the days, she breaks into his apartment and cleans the spaces in which he relives memories of his flight attendant girlfriend. The romanticism with which Wong manifests these memories is pure nostalgia. A free floating camera breathes in the steamy air of the couple on a hot afternoon, and 663 narrates these memories with the hindsight of his dashed dreams.

Love is ever-elusive in a world where no one is quite ready to act on their emotions when opportunity presents itself. When 663 and Faye eventually entertain the possibility of each other, Faye flees, repressing her feelings for fear of losing her freedom. This itself is a paradox that is continually explored in Wong’s work: the potential for joy in self-sacrifice, a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. In a sense this the director’s caution to his audience, to make oneself as emotionally available as humanly possible.

Despite this, the second story and its conclusion is considerably more elevating than the first. Even with its poignant commentary on the tenuity of relationships and possibility, the second story offers a sense of balance in this troubling reality. The first story only leaves the viewer with a sense of what could have been – the characters of policeman and drug smuggler merely dramatize their failure to connect. However, here, too, the director offers an emerging insight, that sometimes a camaraderie between lost souls can be enough.

Common in Wong’s work, plot coherence is not a concern of the film. The narrative takes unannounced leaps in perspective and – as seen in Days – seemingly unrelated characters are given equal attention. Rest assured, even characters who never meet in Wong’s films are connected; thematic and emotional ties run through all examined lives. However, this approach to narrative can be troublesome for viewers.

Wong’s unconventional and expressionistic treatment can be hard to follow, but the symbolism and subtlety of poetic gestures lend a poignant gravity to the film as a whole – expiration dates, cans of pineapple, the preoccupation with “freshness.” Wong’s sympathies for the private and romantic are not found in carefully drawn plot points, but in small acts of personal significance, the gesture of a boarding pass drawn on a napkin or a spare glass hidden away until it’s needed (As Tears Go By).

The director traverses the most sensitive terrain of human needs and desires as a poet, through imagery and sound, the juxtaposition of the inner and outer, and utterly expressionistic flourishes of humanity. Chungking Express is perhaps the most seminal of Wong’s early films. While Ashes presents a profoundly elliptical narrative, it is Chungking Express that captures the true essence of intimate lives in modern Hong Kong. It is the very timeliness of this work – and those to follow – that establishes Wong Kar-wai as a voice of eternal human longing, at once nostalgic and prescient, but always of the moment.

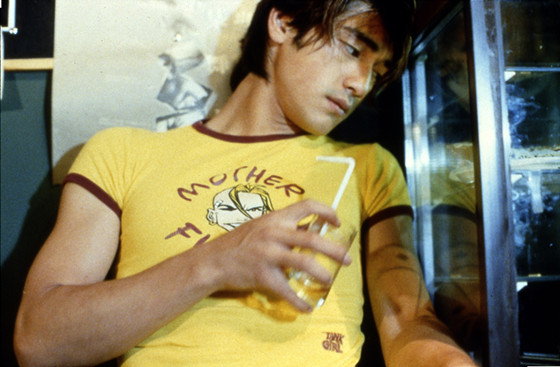

5. Fallen Angels (1995)

Fallen Angels can be assessed as a companion piece to Chungking Express – the same settings, aesthetics, and themes abound. Like Chungking Express, Angels presents two stories that have little to do with one each other besides a few chance encounters between the characters.

The first story concerns a hit man and a woman referred to as his “partner.” The two rarely rarely interact, but the woman cleans up his apartment and sends him the information for his hits. The second story concerns a delinquent young man, Ho Chi Moo, who has escaped prison and lives with his father. The woman from the first story happens to live in their building.

As extensions of Chungking Express, both of these stories deal with the existential implications of modern life in Hong Kong, i.e. alienation and loneliness despite the dense physical proximity of people. This conflict is reinforced by the spatial relations that Wong establishes; locations are revisited, characters seems to just miss each other, in passing, unaware of the camaraderie in their feelings, so to speak.

The result is an overwhelming repression of needs and desires. Wong’s characters are not ignorant of their feelings but their trouble is that they do not express themselves. This manifests as violence or a mentality of fatalism, emotional volatility masquerading as nihilism.

The hit man in the first story embodies this repression. In voice-over, he explains that one’s career is intrinsically linked to one’s personality: as a contract killer, he doesn’t have to make any decisions; someone else decides who should be killed, when and where. He is effectively removed from his profession. Murder distorts time; when he does his hits multiple juxtaposed camera angles refract and repeat the violence, gunshots fall out of sync, and the man’s affect is cold, removed. The repression of characters’ innermost feelings creates this metaphysical gravity, a distortion of time and space.

This is most effective in moments with the hit man’s partner. She is perhaps the most alone of all the characters in the film, and this loneliness often manifests in heavily distorted aesthetic choices. In an early scene where the woman is in the bar where the hit man often hangs out, images of glowing orange liquid coursing through the jukebox induce an almost hypnotic state.

Together with the musical choice (“Speak My Language” by Laurie Anderson), the effect is haunting as the woman daydreams about the man. Her longing and desire bubble beneath the surface before Wong cuts to the swirling neon-washed Hong Kong night, and finally the woman’s repression culminating – temporarily – as she masturbates in the man’s bed.

Early on in the film, the hit man briefly meditates on the nature of strangers, precluding his run in with various characters who will effect his life in various ways. It also becomes a contemplation on identity when strangers are mistaken for characters of one’s past. The willingness of an eccentric prostitute to accept the hit man as her ex-boyfriend becomes something of a revelation for him.

Upon recognizing such emotional vulnerability, he enacts to effectively make a decision in his life. Seeing into the sufferings of another person, in essence, allows him to accept the responsibility for his complicated relationship with his partner. This realization that he must account for his actions comes too late for him, but it strikes Wong’s resonating thematic chord at the center of our modern lives.

The second story concerns Ho, the escaped convict, and his alienation as opposed to the fatality in the first story. A mute who lives with his father, Ho spends much of his time in hiding and goes out at night to reopen shops and sell their goods to unwilling customers. When night after night he runs into Charlie, who is trying to get over her ex-boyfriend, his life is changed forever as he experiences a fulfilling love.

There is a suggestion that the girl’s ex was stolen from her by the same prostitute that the hit man spends time with, and thus he is the man she is trying to get over. This intangible connection between characters is a trademark of Wong’s work; people who never meet – or the audience never sees – are related to others in subtle and often romantic ways.

Even in Charlie’s company, Ho is alienated, as he is never the focus of her attention. He accepts his position as he falls in love with her, but he is ultimately forgotten. He escapes a physical isolation into another, deeper kind. His strange, forced interactions with people in the middle of the night are his only form of human contact. These incidences are always comical rather than threatening; his “customers” are sympathetic rather than frightened.

There is a lightheartedness to these scenes, a sense of brevity and innocence. However, Ho, too, eventually must take responsibility for his actions, as the hit man learns, but this revelation is no means of a payoff in terms of any kind of fulfillment.

Wong’s characters learn about themselves through their experiences – issues of identity being the crux of all human isolation and longing – but this in no way guarantees genre expectations. In Wong’s films, the revelation of the individual is often inconsequential, sometimes fatal, but the emphasis remains on the individual. The troubled relationships between characters all return to the broken identities that make them up.

Wong’s preoccupations with time, memory, and nostalgia enact both a transient and an eternal quality at the same time. Wong insists that one’s identity – and the tragedy of the human condition – is understood through such sufferings of the soul. By experiencing loss, regret, and reflection, we are intimately acquainted with the very transience that gives weight to our humanity.

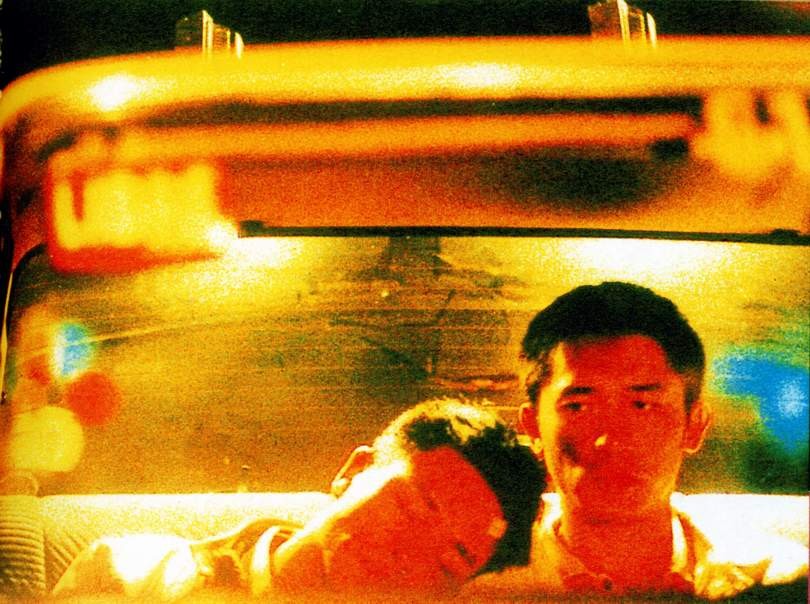

6. Happy Together (1997)

This film marks one of Wong Kar Wai’s most cohesive works, in terms of both his aesthetics and thematic intent. Led by such opposing forces as Leslie Cheung and Tony Leung, Happy Together tells the story of two lovers caught in an abusive cycle of destruction and dependency. Cheung reprises a role similar to his character in Days of Being Wild, an uncommitted and emotionally vapid lover, Ho, while Lai, played by Leung, is prey to his endless promises of starting over.

Common in Wong’s work, the film begins with a character speaking in past tense via voiceover, contemplating the consequences of actions yet to happen. More than in any other of his films, Wong deals most directly with cycles and their effect on people here. The two men have traveled to Argentina in an attempt to renew their relationship, but before long Ho leaves Lai again. Wong makes exceedingly drastic aesthetic choices to visualize Lai’s emotional chaos as Ho emotionally tortures Lai.

An unpredictably shaky camera searches for its bearings, music selections pop into moments of fitting, and garish neon light soak the walls of interiors – a color palate that is at once putrid and beautiful. At this point, the usually detailed-oriented Wong is not so much concerned with legibility as he is with impressionism, capturing his character’s inner turmoil and turning it inside out.

As Wong would have it, Ho shows up at Lai’s door beaten to a pulp and in need of care. Lai takes him in, but keeps him at a distance both physically and emotionally, despite Ho’s advances. Eventually, though, Lai relents. Lai remarks in voiceover that this was the happiest he’d ever been, despite his awareness that Ho’s affection is contingent upon his dependence.

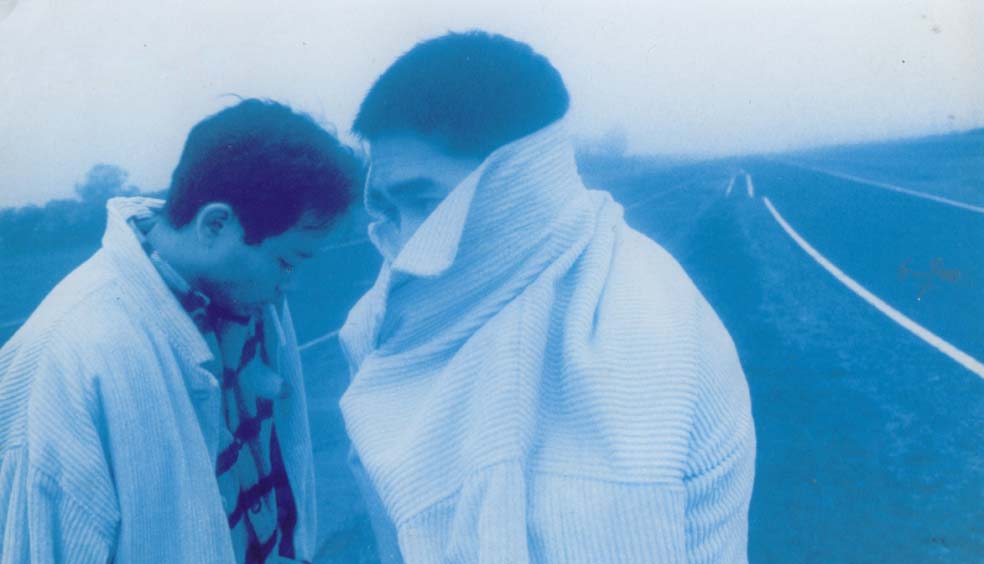

This is thematically significant as a key to understanding Wong’s work as a whole. Dramatic “logic” – as one would assume – is thrown to the wayside to instead focus on the director’s true interests; despite awareness and logic, Lai cannot leave Ho because he is entrenched in the most eternal conflict: an individual in the face of faltering ideals. Of course, there is the physical conflict of isolation in a foreign place, Lai as an expatriate in Argentina with no immediate means of getting home, but this is a relatively simple narrative concession granted which helps to reinforce the singularity of his true conflict.

Wong assures this reading through the leitmotif of the Iguazu waterfalls, the initial reason for Lai and Ho’s trip to Argentina. In these images, the camera floats over the falls just long enough to induce meditation, and then they’re gone. This location is attributed symbolic significance, another trademark of Wong’s work; as some places become significant based on what occurs there, the falls represent an unrealized potential, a looming ideal that has since lost its perceived meaning.

The director confronts cyclical human nature most directly through Lai’s final rejection of Ho. Lai is unsurprised by Ho’s abusive behavior when he recovers, but his sadness transforms into dignified anger and a commitment to his own emotional well-being. Lai is ultimately able to reject Ho and realizes through friendship that his relationship with Ho is an ideal which cannot exist.

However, even his friendship must end, and at his lowest Lai comes to finally understand Ho. Again, Wong’s characters’ resolve come from experiences of considerable emotional depth. From his shattering ideal of love, to his redeeming friendship, and then his complete alienation, Lai is able to gather the pieces of his identity and confront his past.

In this film, Wong effectively closes off the cycles that he sets in motion, or rather, realizes his characters trapped within. Naturally, there are loose ends, but Happy Together feels like the director’s most cohesive work up to this point. Here, he seems to have stuck a balance between his narrative predilections and thematic intent.