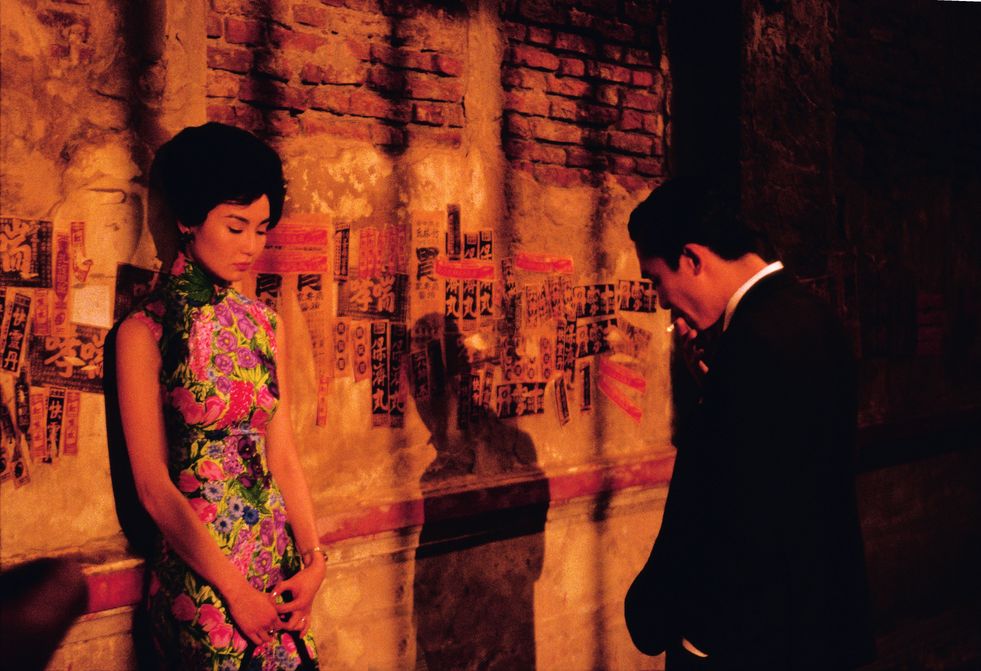

7. In the Mood for Love (2000)

Widely regarded as Wong Kar-wai’s masterwork at this point in his career, In the Mood for Love constitutes the second entry into his informal trilogy (Days of Being Wild, 2046). Set in 1960s Hong Kong, this film bears all the marks of Wong’s Romantic vision –– isolation in densely populated areas, longing for intimacy and fulfillment circumscribed by social forces, an urban setting which at once exudes nostalgia and modernity. At the forefront are Su Li-zhen and Chow Mo-wan, played by Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung, respectively. This film, and those aforementioned, create a story of boundless emotion and eternal longing which supersedes any narrative discrepancies.

On the same day, Su and Chow both move into an apartment building and become neighbors. Each of them has a spouse who frequently leaves them alone to work late, and despite the friendly landlady, Mrs. Suen, they each find themselves alone, confined within the thin walls of their apartments. Wong capitalizes on motif, allowing locations and actions to take on meaning through repetition, nuance, and subtle changes.

Everyday interactions and chance encounters defy common romantic genre expectations. The characters’ lives intersect to no avail; Su and Chow frequently cross paths on their way to and from the street noodle stall, exchanging silent greetings and continuing along. Rather than linger on these encounters, Wong instead focuses on the characters separately, the banality of everyday unfulfillment. This conceit is, in fact, an outright declaration in the original Chinese title of the film, which refers to a metaphor for the fleeting nature of time, beauty, and love. It is a longing which permeates the core of the characters’ souls.

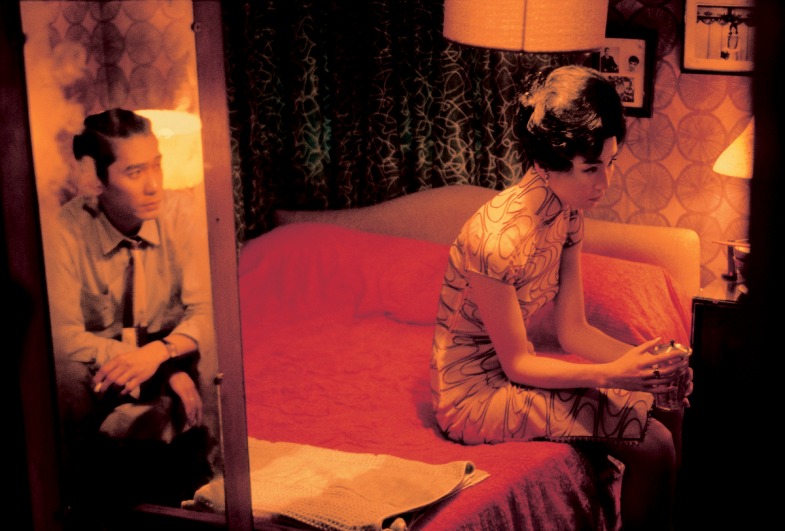

The inevitability of the characters’ union is set into motion by their shared realization that their respective spouses are seeing each other. Even from the start, this bonds Su and Chow together in a plainly platonic sense, thus their relationship begins. And their relationship is innocent in that Chow asks Su to help him write a martial arts serial for the paper he works for. However, in the social context of the times, even this solicits speculation, so Chow rents a hotel room where they can work in secret.

The two seemingly trade their isolated apartments for a rented room and begin to share meals together, a reversal of the earlier motif of separation. As their relationship develops they discover that they have feelings for each other, but their feelings never materialize as it is implied that they are morally above their spouses. This illustrates a conviction of Wong’s vision, that while the social norms and conflicts of modernity are hinderances upon human connection, issues of morality are ultimately held in opposition to fulfillment. It is the ever-present conflict between the daily life of the individual and the ideals he or she aspires to.

When Chow confronts his feelings and asks Su to leave with him, she fails to accept – a mere fault of chance, or an eternally departed potential. Even the attempt to reach out by one character ends in checking herself against doubt. The eventual transgression of the platonic boundary placed on their relationship is a direct consequence of their unrelieved repression. However, despite the acknowledgement of this gesture, their feelings still fail to materialize.

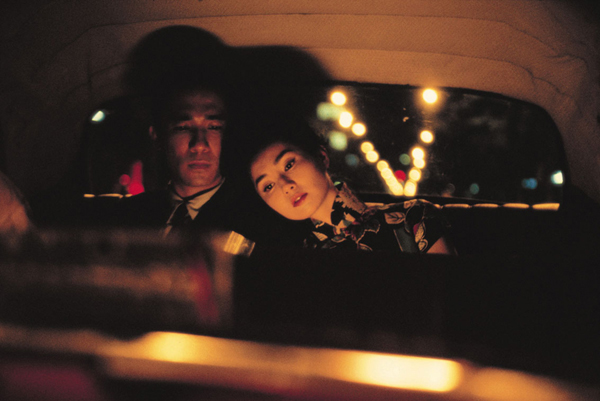

Emotions bubble beneath the surface until they demand expression, but the characters are always restrained by a fear of the same sense of emptiness that they presently suffer from. A pervading nostalgia harbors all missed opportunities, regret, and moral contemplations faced by the characters, continually leading them into conflict with the ideals they long after. The pattern of missed connections juxtaposed with physical proximity thus becomes another contemplation on chance and fate, a predetermined loneliness or the tenuity of fulfillment. Either way, lasting happiness is always just out of reach.

At the end of the film, the director again creates a symbolic tension from a particularly meaningful location. Chow fulfills a prophecy made earlier in the film when he journeys to the Angkor Wat in Cambodia and whispers a secret into a wall and covers it. This is the repression at the core of Wong’s sensibilities as a director.

The ultimate inhibition of peoples’ emotional freedom and fulfillment is not social, not even moral, but it is the lack of self-understanding, and therefore the means to connect with others. Despite the influences of chance, fate, and free will, Su and Chow never allow their true emotions to bloom. What remains is a silent resignation, a memory, a secret of another life which may as well have been a dream.

In the Mood for Love is Wong Kar-wai’s most lyrical film to date. It is a film which seeks to portray the individual’s inner life through image and sound. Wong Kar-wai fully establishes his dominion over the traditional narrative. His refusal of such structures is not a rebellion against them, but a necessity of the material he serves. The exploration of such intimacy, repression, and longing depend not on plot developments but one’s experience of everyday life.

The director enlivens his characters’ surroundings with such beauty and poetry that their isolation is a natural contrast to the possibilities of life. With In the Mood for Love, Wong Kar-wai situates himself as one of cinema’s most contemporary Romantic tragedians.

8. 2046 (2004)

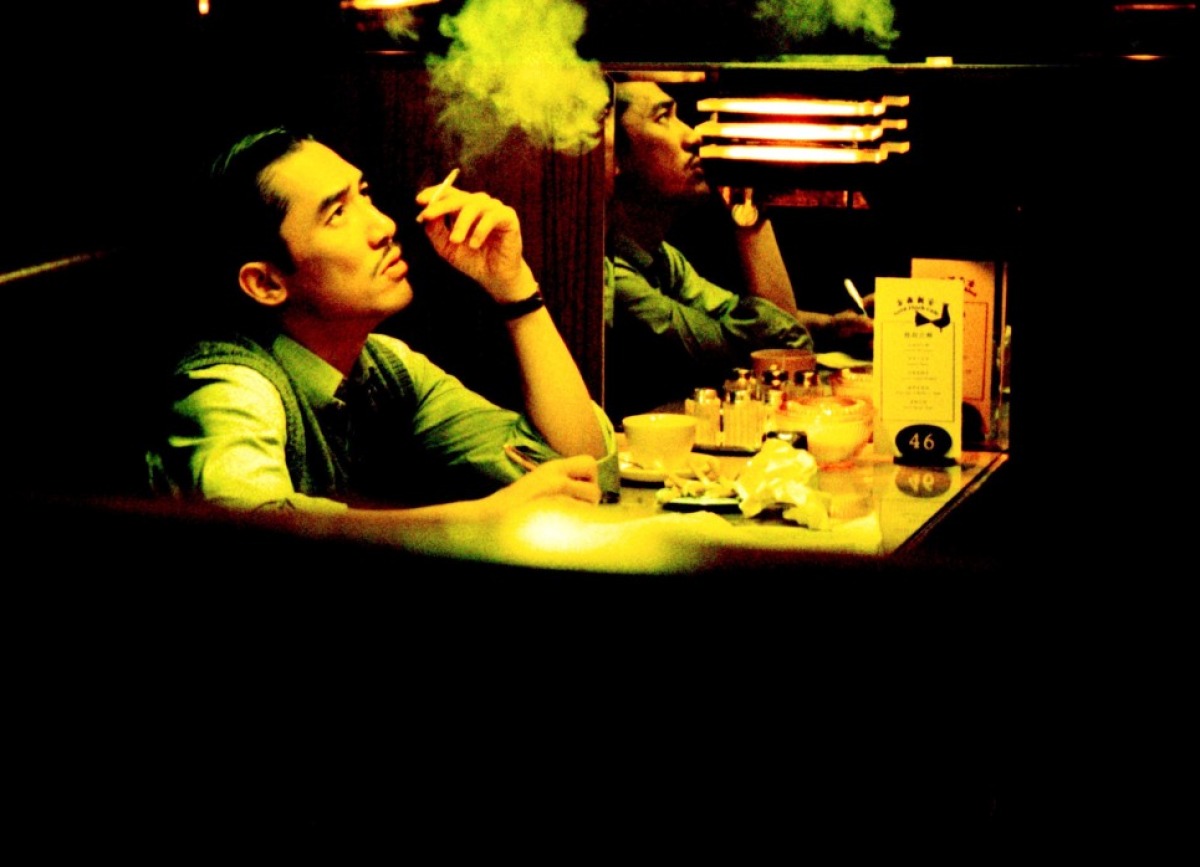

The concluding chapter of Wong’s informal trilogy is by far the most complex. 2046 is comprised of four stories woven together without respect to any chronology. Three of the stories are about Chow’s (the role reprised by Tony Leung) relationships with other women after losing Su Li-Zhen. The fourth story takes place in Chow’s science-fiction fantasy, the titular “2046.”

The structure of the film inherently modulates the viewer’s experience to be something more akin to memory than its mere representation. In this film, Wong Kar-wai seamlessly merges form with function; one experiences this film individually, taking away whatever resonates most in its subtle progression of tones and moods. In this way, synopsis is of little value, and a single viewing does not suffice to gleam Wong’s delicate sensibilities here.

At the heart of the film is Chow’s conflict of getting over Su Li-Zhen while still longing for the ideal that she represents. Wong maintains thematic consistency from In the Mood for Love while still making 2046 thoroughly original. This is largely due to the infusion of science-fiction elements – which resound poignantly and without contrivances throughout the film – but also Wong’s sensitivity to tone.

Like its predecessor, this film deals with the repression of not only one’s emotions but of one’s identity. However, where In the Mood for Love probes the nature of loss, 2046 explores how one attempts to recover from it. In time, such depression callouses, and the director navigates the transition with unabashed humanity.

Aesthetically, the film marks a deviation from Wong’s previous work. Rather than render his interiors in harsh florescent colors, the director opts for a cleaner look. Whereas his previous films saw characters bathed in whatever the ambient light, 2046 feels more balanced. Faithfully rendered skin tones pop from color-controlled sets, often charged with red-green, green-blue split-compliment palettes. Wong exceeds his own high standards of detail and meticulousness; every composition has a specific weight and impact, and visual symbols such as mirrors, windows, and other means of separation or looking-in abound.

One crucial moment shows Chow on the street outside of his office, looking through the window at a woman he has feelings for as she talks to her ex-boyfriend on the phone. He watches how happy she is as the neon lights reflect back at him in the window. This moment presents a critical revelation on the path to Chow’s recovery. Each shot throughout the film renegotiates the shifting relationships between characters. Overall, 2046 feels like Wong’s most controlled, visually assured film up to this point.

The structure of the film does present significant difficulty in terms of overall comprehensibility. The chapters of the film move seamlessly throughout time and space, as well as other dimensions of reality, with only the slightest hints to the true chronology of events. Chow philanders through his life after Su Li-Zhen, and the chapters of the film focus on his relationships with three particular women – while quite a few more are implied. After losing his idealized love, Chow busies himself in the role of the much desired ladies’ man, however, his eternalized longing is never actually hidden.

The films begins with an introduction to Chow’s fictional world of “2046,” narrated by his main character. The future is a vast and lonely place where individuals try to recapture their lost loves by taking a long train ride to the world of 2046 – where, supposedly, nothing ever changes and is therefore idealized. Despite this degree of self-awareness, Wong’s theme-driven direction sees Chow through his attempts to satisfy – or at least quell – his longing through other people.

Gradually, Chow learns from his subsequent relationships that his idealized love is irreplaceable, and that his attempts to find Su Li-Zhen in others are morally and emotionally abject. Filtered through the director’s sensibilities and tonal acuity, though, the human condition is rendered as beautiful rather than lamentable. Where untamed carnality stands opposite of Chow’s true love, the most triumphant moments in Wong’s experience are those of warm affection and camaraderie, friendship – a balance and solidarity in life. Thus the director offers his remedy to the realities of heartbreak, isolation, and romantic longing.

Although 2046 lacks the containment of the director’s other works, its cinematic value remains unscathed. More poem than plot, chaos than order – the inventiveness, ambition, and scope of the film attribute to a peak in Wong’s profundity. The experiences and insights within are worth many times over the challenges they present.

9. The Grandmaster (2013)

Wong Kar-wai’s latest film deviates from all of his previous work in a significant way. The Grandmaster tells the true story of Ip Man’s life and the rise of Wing Chun as a martial art. The film is thusly part biopic, part period piece, and part genre film. In form, it is quite different from anything the director has done before. However, in content and theme, Wong Kar-wai is present at his most compelling; he effectively concentrates his twenty years’ practice on the story of a man whose real-life struggles exemplify the themes that the director has dealt with all along.

Played by none other than Tony Leung, the Wing Chun grandmaster, Ip Man, proves to be the essential Wong Kar-wai protagonist. The move away from a contemporary Hong Kong setting is a move to expand the director’s cinema, as the story not only embodies his deepest thematic concerns, but goes back in time to critical events in mainland China’s history. The film is then comprised of yet another part: part invigoration of the Chinese national cinema. With The Grandmaster, Wong Kar-wai expands his oeuvre in both width and depth.

The film presents a refreshingly refined narrative; frame loosely around the Second Sino-Japanese War, it chronicles the events of Ip Man’s rise to grandmaster of the South, life, and legacy. However, the film devotes a significant amount of its narrative to following the longtime relationship between Ip Man and the daughter of the retiring Northern grandmaster.

Rather than explore his themes of fulfillment, connection, etc. in the foreground, Wong instead recognizes these elements in an individual whose stable life is shaken by real events. Thus, the film is effectively about before and after, a meditation presented throughout Wong’s work, often in the forms of regret and longing. The historical narrative, however, keeps the film moving. Wong doesn’t take the poetic license to linger but rather posits these moments between before and after for contemplation as they occur.

The Grandmaster deals with binaries on several levels. The first scene, a remarkable fight sequence in the pouring rain, serves as a kind of mission statement for the film. Ip Man himself provides the first binary to an unseen party: “Horizontal. Vertical.” In his thinking, this is the essence of Kung Fu, fall down or stay standing. And the ensuing street fight reinforces this conceit: Ip Man defeats a crowd of challengers without receiving so much as a single blow.

He fights with the kind of precision that looks effortless, despite the flurries of crushing blows and bodies flying through the air. It isn’t until a lone rival enters that the sheer physicality of the combat is understood. In fact, the effect presents yet another binary, the physical and metaphysical. Kung Fu is effectively a form of transcendence; despite its brutality, it appears as more art than combat.

This meditation on binaries and their transcendence into a more complex uniformity is realized at a critical moment. Ip Man’s“fight” with Gong Yutian, grandmaster of the North, is an exchange of ideas rather than a physical encounter, the ultimate marriage of two opposites in Kung Fu. From here, though, the film goes in a more familiar direction. With the retirement and defeat of her father, Gong Er becomes Ip Man’s lifelong adversary and friendly antagonist. Wong charts the relationship between these two characters – united opposites of North and South – through their letter correspondence and Ip Man’s concern for the vengeance that drives Gong.

The film centralizes on the juxtaposition of the characters’ lives after the war. While Ip overcomes his traumas and goes on to establish his school, Gong strays from her martial arts. At the heart of this juxtaposition is the camaraderie that binds the two together. Although it’s never so much as alluded to, the relationship between Ip and Gong is palpably romantic. That she falls in love with him is tellable from the first time she challenges him.

The fight choreography is more intimate than any other instance in the film, and Wong photographs it with considerably more close ups than the others. The camera focuses on ways to keep the characters together rather than favoring, including a dazzling overhead shot that sees the two more as dancers than combatants.

There is repression here as there is at the core of all Wong’s work. When Gong invites Ip to the North for a rematch there is already an implication that her invitation is more than literal. And of course there is more that separates the two than North and South. Instead of probing the moral consequences of longing – as in In the Mood for Love – Wong examines two individuals who are resigned to their separate paths, with martial arts as both a crucial and ostensible backdrop.

The director thusly strikes a similar thematic chord in a far more subtle way with this historical-genre film. The deftness and craftsmanship of The Grandmaster as a commercial production – this while preserving the intangible qualities that audiences view Wong Kar-wai for – is perhaps the most significant development in the auteur’s career to date.

In far greater respects than a departure from form, The Grandmaster is a bold statement in Wong’s career. His collaboration with China’s mainland film industry speaks to much more than a transition from art house to commercial interests. If Wong Kar-wai had guaranteed his legacy as one of the greatest Romantics of cinema prior to The Grandmaster, then perhaps it is already time for a greater appraisal of the director’s work.

Author Bio: Kevin Pementel is a Chicago-based filmmaker and film writer.